Background

The social phenomenon of the flapper emerged after WWI in what was called the “Roaring Twenties” — a period of great economic and social change in American history. Young people of this generation had been particularly affected by the Great War (WWI). Over 116,000 young American soldiers died, and 200,000 were wounded. In addition, between 1918-19, 650,000 Americans, most of them young people, died in the influenza pandemic which killed millions worldwide. The post-war generation felt that they had suffered due to the poor decisions made by their parents’ generation. They began to question the values and traditions that led to these cataclysmic events, and they sought out new ideas and new meaning in their lives. Often, that desire for something new became a rebellion against the things their parents represented, and for young women in particular, that included the seemingly limited lives of their mothers.

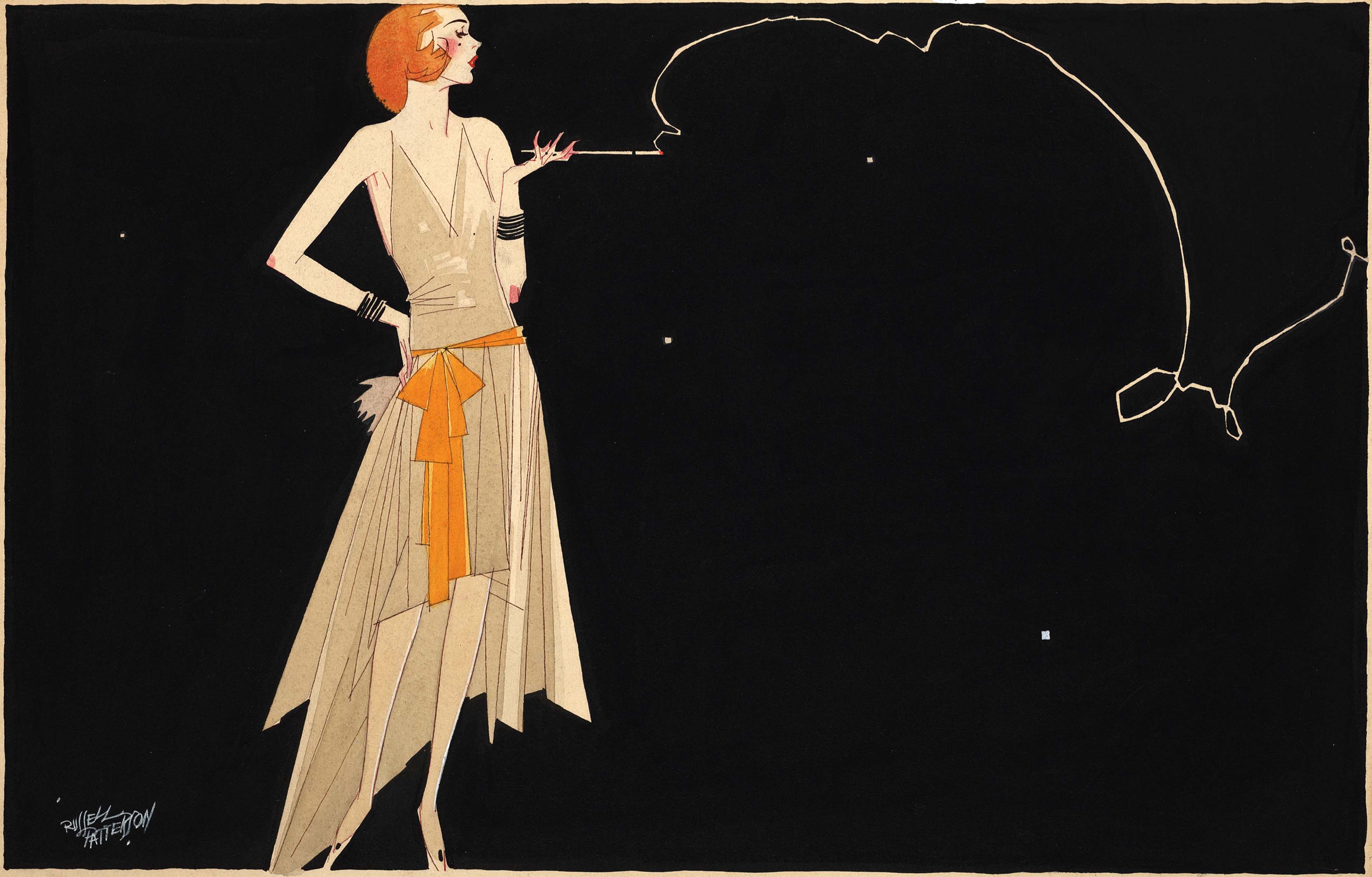

Women who openly questioned their mothers’ morality were often called “flappers.” Flappers broke with old traditions in various ways. They threw their corsets away, wore looser clothing that did not restrict movement, and had a preference for shorter skirts. They cut their hair quite short in what was called a “bob” and wore makeup. They listened to the new music of black musicians called jazz, and they danced openly in ways their parents considered loose and provocative. They drank and smoked and learned to drive automobiles. And they often treated sex casually, as a means of self-expression, and regarded marriage as something not to be rushed into. In effect, they ignored the rules of acceptable female behavior.

Flappers were aided by new political and educational roles for women. The 19th Amendment was passed shortly after the war, and women now had the right to vote. Women played a prominent role in the normal education movement (the creation of teachers’ colleges) of the late 19th century, opening the teaching profession to a greater number of women. In addition, in the early 20th century communities across the US were opening secondary schools, and young men and women were both attending and socializing in coeducational institutions, taught by both male and female teachers. Women could readily be found in colleges, though not in great numbers, seeking degrees not only in teaching but also medicine, law, and engineering. Yet, women were beginning to see female role models everywhere.

Additionally, the 1920s was a time of increased consumerism. Working women with paychecks could control their own money. And the growing American economy offered many new products and services on which to spend that money. Products were not only utilitarian, they were marks of prestige. For the first time, Americans began to pay attention to the brand name of a product and the prestige that certain brand names gave them. New ways of advertising appealed to current fashion using psychology to sell the “right” automobile and the most stylish clothing. Tobacco companies began to market products to women. Flappers were closely associated with the new consumerism.

The public image of the flapper was never that of a working-class woman. Normally, the most famous flappers were from wealthy families, and middle-class daughters followed that social lead rather than the example of their mothers. The rising movie industry reinforced the flapper image. Some of the most famous movie stars of the 1920s set the tone with provocative clothing, sexual escapades, and high-living lifestyles.

Historians have grappled with the question of the flapper in feminist history. Was the flapper a version of feminism — the cultural and social aspect of women having a larger political role in society? Or was she merely a “frivolous” detour along the journey to full women’s rights? We may look back a century and wonder what all the fuss was about. But at the time, magazines and newspapers were filled with analyses and opinions regarding the flapper.

- Summarized arguments in defense of the flapper:

- She has no intention of being defined by men and has the right to explore her own way in a free-spirited manner.

- The flapper makes the obvious case that she will have children and family in her own time and way and will not be dictated to by family or society.

- Coeducation is good for society and is far more healthy than the segregation of the sexes. If men and women are ever to be equal, they need to socialize with one another from a young age.

- The flapper’s behaviors are not frivolous but signs of growing independence which can be expressed in many ways.

- Despite the false characterizations of some establishment figures, flappers are intelligent, well-read young women. They have to be. Compared to their mothers who were “pretty birds in a cage,” women today have to form their own opinions from what they read and see.

- Flappers should not be judged against the whole of the feminist movement. They contribute in one way, the social aspect, to the long march toward equality of the sexes.

In an article she wrote for the New York Times, Ruth Hooper, a flapper, made the following argument in defense of the flapper’s viewpoint:

A flapper is proud of her nerve — she is not even afraid of calling it by its right name. She is shameless, selfish, and honest, but at the same time she considers these three attributes virtues. Why not? She takes a man's point of view as her mother never could, and when she loses she is not afraid to admit defeat, whether it be a prime lover or $20 at auction. She can take a man — the man of the hour — at his face value…with no foolish promises that will need a disturbing and disagreeable breaking.

- Summarized arguments critical of the flapper:

- At her core, the flapper is simply a self-absorbed and self-indulgent young woman; nothing more.

- She is actually a creature of consumerism; her time and money is spent on clothing and makeup.

- While she claims to be independent-minded, she is actually slavishly following fashion in an effort to be part of the “in” crowd or a supposedly stylish group.

- Flappers are unconcerned with the plight of women in general; they are interested only in their own class. They have made no significant contributions to the cause of women in general.

- These women are simply making a virtue out of sinful behaviors such as smoking, drinking, partying, sex, and so on.

- The flapper neglects her family and children.

- Like most self-absorbed people, the flapper has a cynical world view.

In 1925, New Republic editor Bruce Bliven wrote an article that was, overall, laudatory of the flapper. However, using a rather tongue-in-cheek style of writing about a flapper named Jane, he did a better job than many of the flapper’s critics in summarizing their view of her frivolity:

She is, for one thing, a very pretty girl. Beauty is the fashion in 1925. She is frankly, heavily made up, not to imitate nature, but for an altogether artificial effect — pallor mortis, poisonously scarlet lips, richly ringed eyes — the latter looking not so much debauched (which is the intention) as diabetic. Her walk duplicates the swagger supposed by innocent America to go with the female half of a Paris Apache dance. And there are, finally, her clothes. These were estimated the other day by some statistician to weigh two pounds. Probably a libel; I doubt they come within half a pound of such bulk. Jane isn't wearing much, this summer.