The Social Cognitive Perspective

Note to students: The best preparation for taking the reading quiz is to pay close attention to the key terms as you read. Each question in the question banks is directly linked to these key terms and phrases.

Chapter Focus Question:

Why have personality psychologists elevated the social-cognitive perspective in recent decades?

- B.F. Skinner’s view of personality

- Personality conditioning according to Skinner

- Bandura’s view of reasoning in behavioral learning

- Three components of social-cognitive theory

- Definition of reciprocal determinism

- Definition of observational learning

- Motivation and observational learning

- Self-efficacy’s relationship to observational learning

Section Focus Question:

What are the components of Albert Bandura’s psychology of the personality?

Key Terms:

Behaviorists and Personality

Generally, behaviorists do not believe in biological determinism: They do not see personality traits as inborn. Instead, they view personality as significantly shaped by the reinforcements and consequences outside of the organism. In other words, people behave in a consistent manner based on prior learning. B.F. Skinner, a strict behaviorist, believed that the environment was solely responsible for all behavior, including the enduring, consistent behavior patterns studied by personality theorists. Skinner disagreed with Freud’s idea that personality is fixed in childhood. He argued that personality develops over our entire lives, not only in the first few years. Our responses can change as we come across new situations; therefore, we can expect more variability over time in personality than Freud would anticipate. For example, you might be a risk-taker when you are younger, but with age and acquiring responsibilities like children, you are more reinforced for more conservative behavior and personality characteristics.

Albert Bandura and the Social-Cognitive Perspective

Albert Bandura agreed with Skinner that personality develops through learning. He disagreed, however, with Skinner’s strict behaviorist approach to personality development, because he felt that thinking and reasoning are important components of learning. He presented a social-cognitive theory of personality that emphasizes both learning and cognition as sources of individual differences in personality. In social-cognitive theory, the concepts of reciprocal determinism, observational learning and self-efficacy all play a part in personality development.

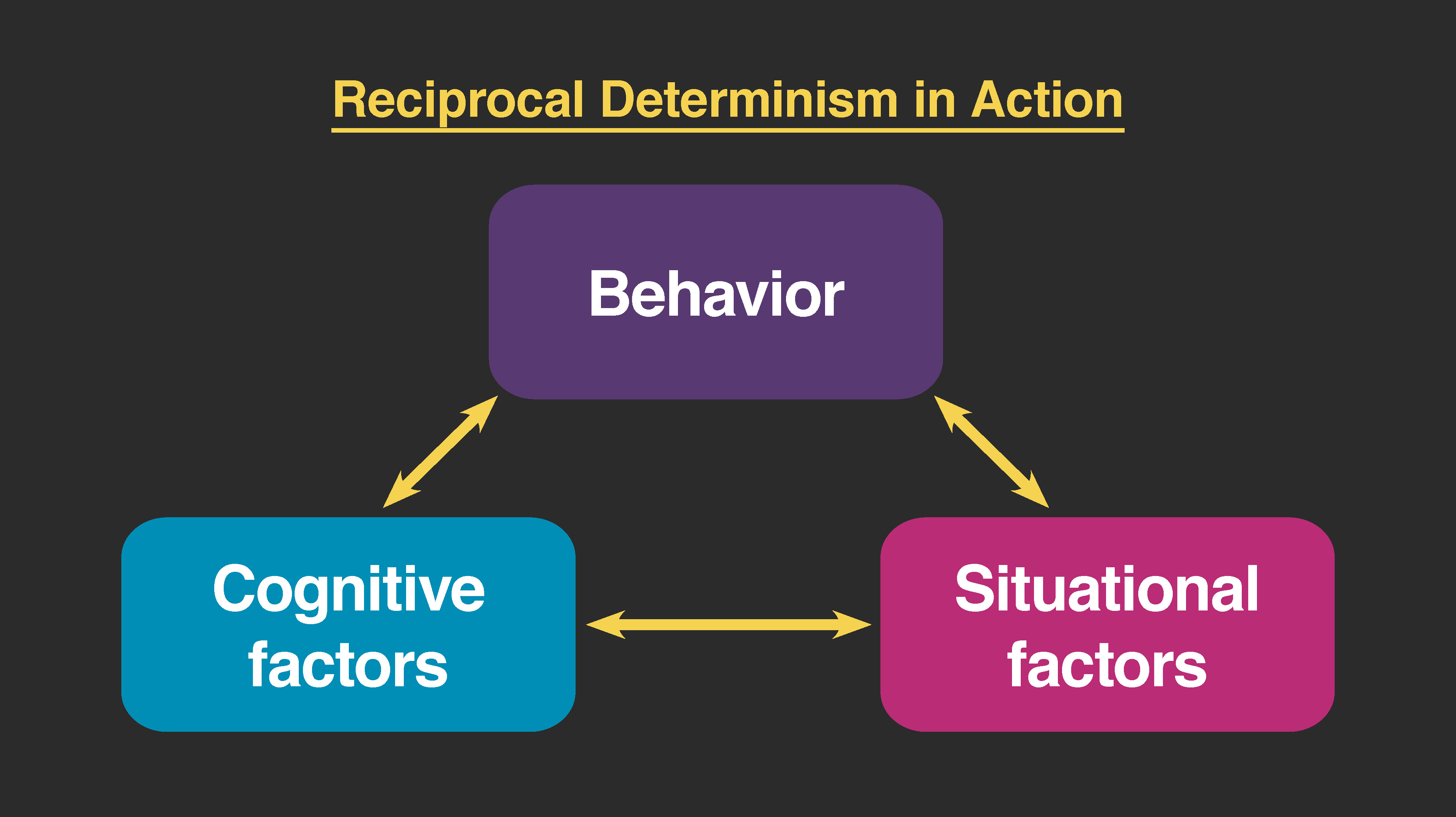

Reciprocal Determinism. In contrast to Skinner’s idea that the environment alone determines behavior, Bandura proposed the concept of reciprocal determinism, in which cognitive processes, behavior and context all interact, each factor influencing and being influenced by the others simultaneously. Cognitive processes refer to all characteristics previously learned, including beliefs, expectations and personality characteristics. Behavior refers to anything that we do that may be rewarded or punished. Finally, the context in which the behavior occurs refers to the environment or situation, which includes rewarding/punishing stimuli.

For example, you might go to a dress-up party where the women are supposed to dress like men and the men like women. Do you dress up according to the themes of the party? The behavior is the dressing up; the cognitive factors that influence dressing up might be religious beliefs or family values or prior experiences with cross-dressing that would mitigate for or against the behavior. Finally, the context refers to the reward structure for the behavior, that is, everyone really has a lot of fun at such a party. According to reciprocal determinism, all of these factors are in play.

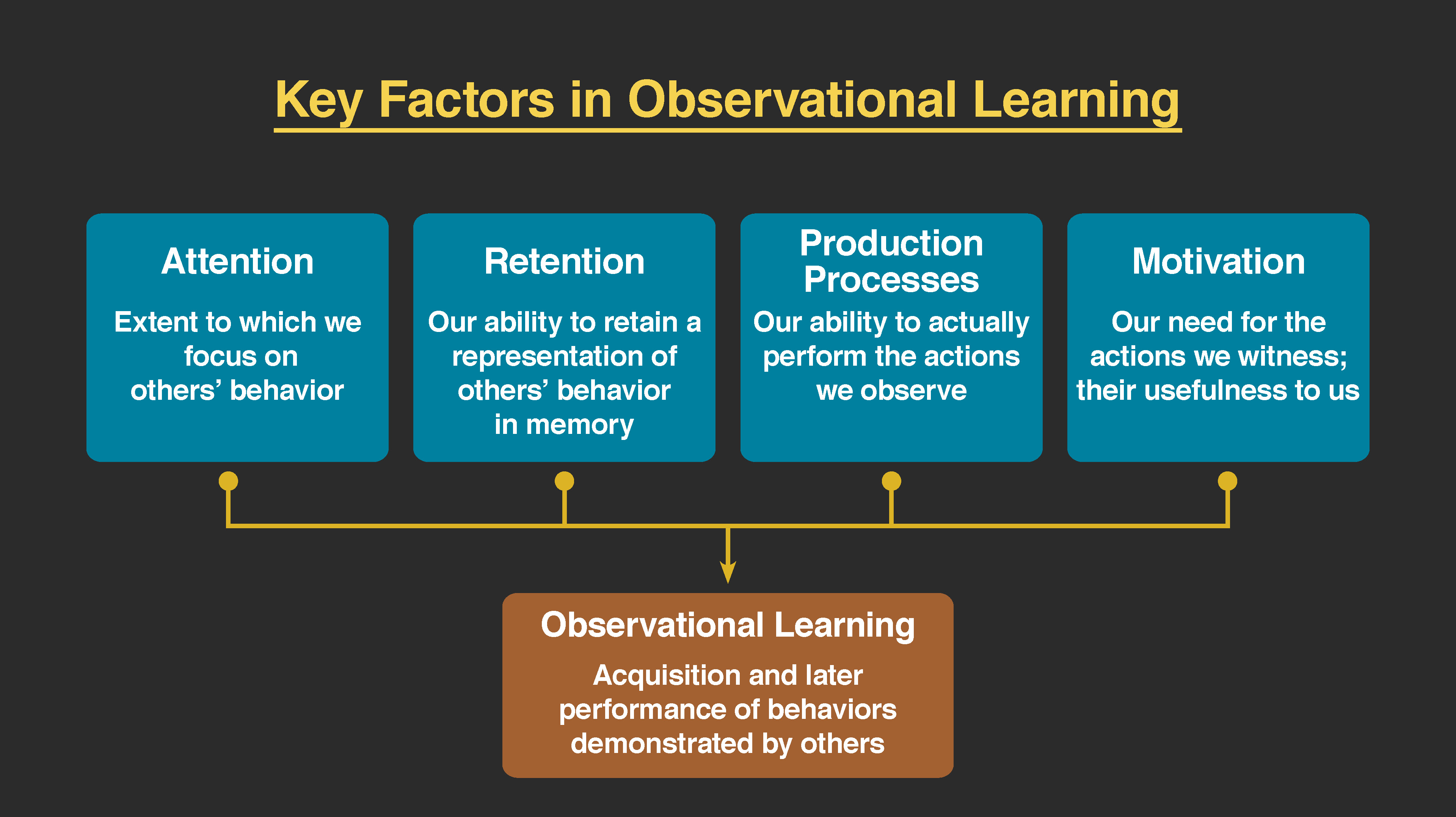

Observational Learning. Bandura’s key contribution to learning theory was the idea that much learning is vicarious. We learn by observing someone else’s behavior and its consequences, which Bandura called observational learning. He felt that this type of learning also plays a part in the development of our personality. Just as we learn individual behaviors, we learn new behavior patterns when we see them performed by other people or models. Drawing on the behaviorists’ ideas about reinforcement, Bandura suggested that whether we choose to imitate a model’s behavior depends on whether we see the model reinforced or punished. Through observational learning, we come to learn what behaviors are acceptable and rewarded in our culture, and we also learn to inhibit deviant or socially unacceptable behaviors by seeing what behaviors are punished. For example, a person might not feel comfortable attending a cross-dressing party if in the past he or she heard friends or family ridicule others who did such behaviors.

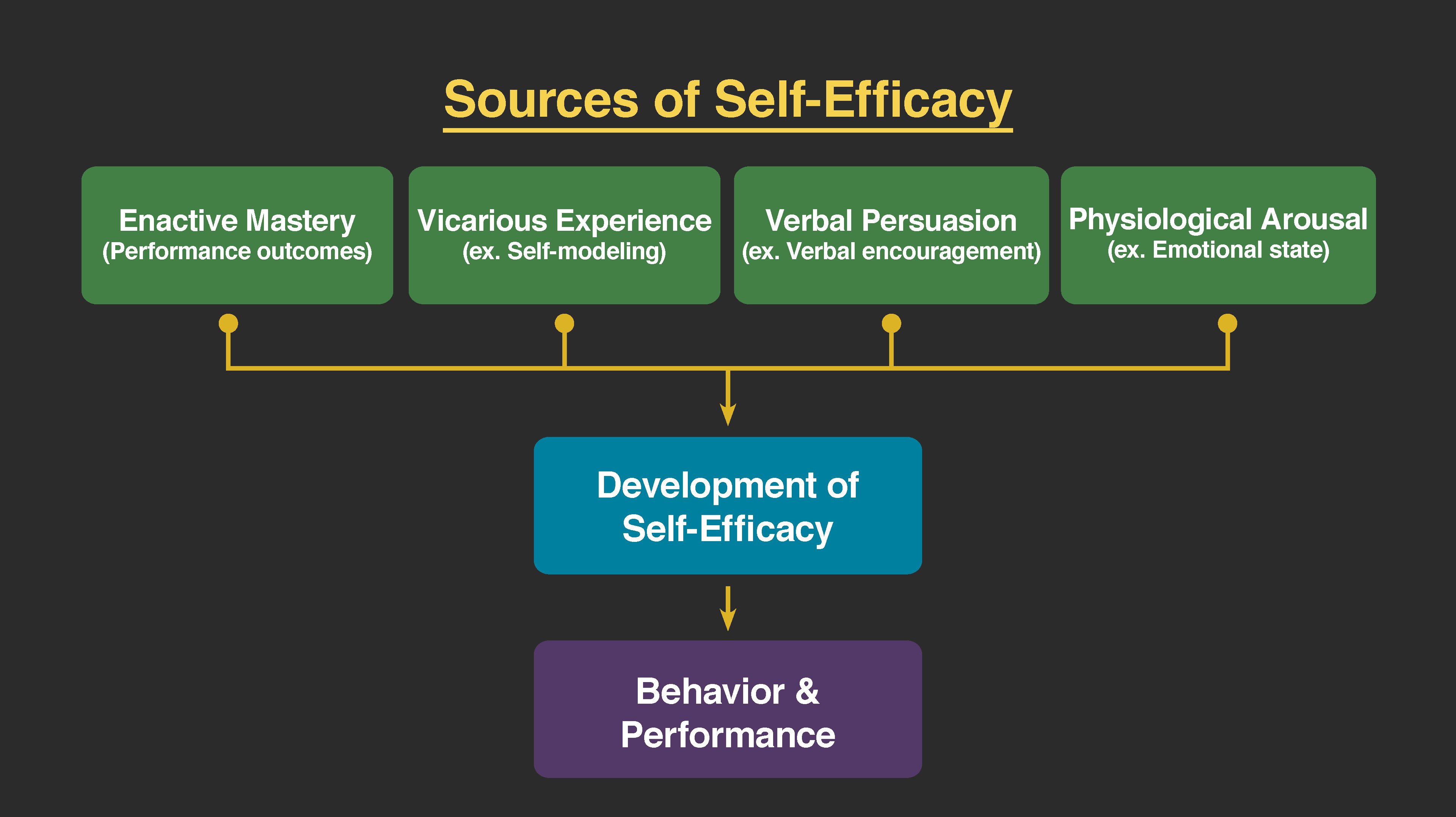

Self-Efficacy. Bandura has studied a number of cognitive and personal factors that affect learning and personality development, and most recently has focused on the concept of self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is our level of confidence in our own abilities, developed through our social experiences. Self-efficacy affects how we approach challenges and reach goals. In observational learning, self-efficacy is a cognitive factor that affects which behaviors we choose to imitate as well as our success in performing those behaviors.

People who have high self-efficacy believe that their goals are within reach, have a positive view of challenges, seeing them as tasks to be mastered, and develop a deep interest in and a strong commitment to the activities in which they are involved, quickly recovering from setbacks. Conversely, people with low self-efficacy avoid challenging tasks because they doubt their ability to be successful, tend to focus on failure and negative outcomes and lose confidence in their abilities if they experience setbacks. Feelings of self-efficacy can be specific to certain situations. For instance, a student might feel confident in her ability in English class but much less so in math class.

Julian Rotter and Locus of Control

- Julian Rotter

- Self-efficacy and locus of control

- Internal locus of control

- External locus of control

- Internal locus of control examples

- Depression and external locus of control

- Internal locus of control and achievement

Section Focus Question:

What is the theory of the locus of control and its impact on personality?

Key Terms:

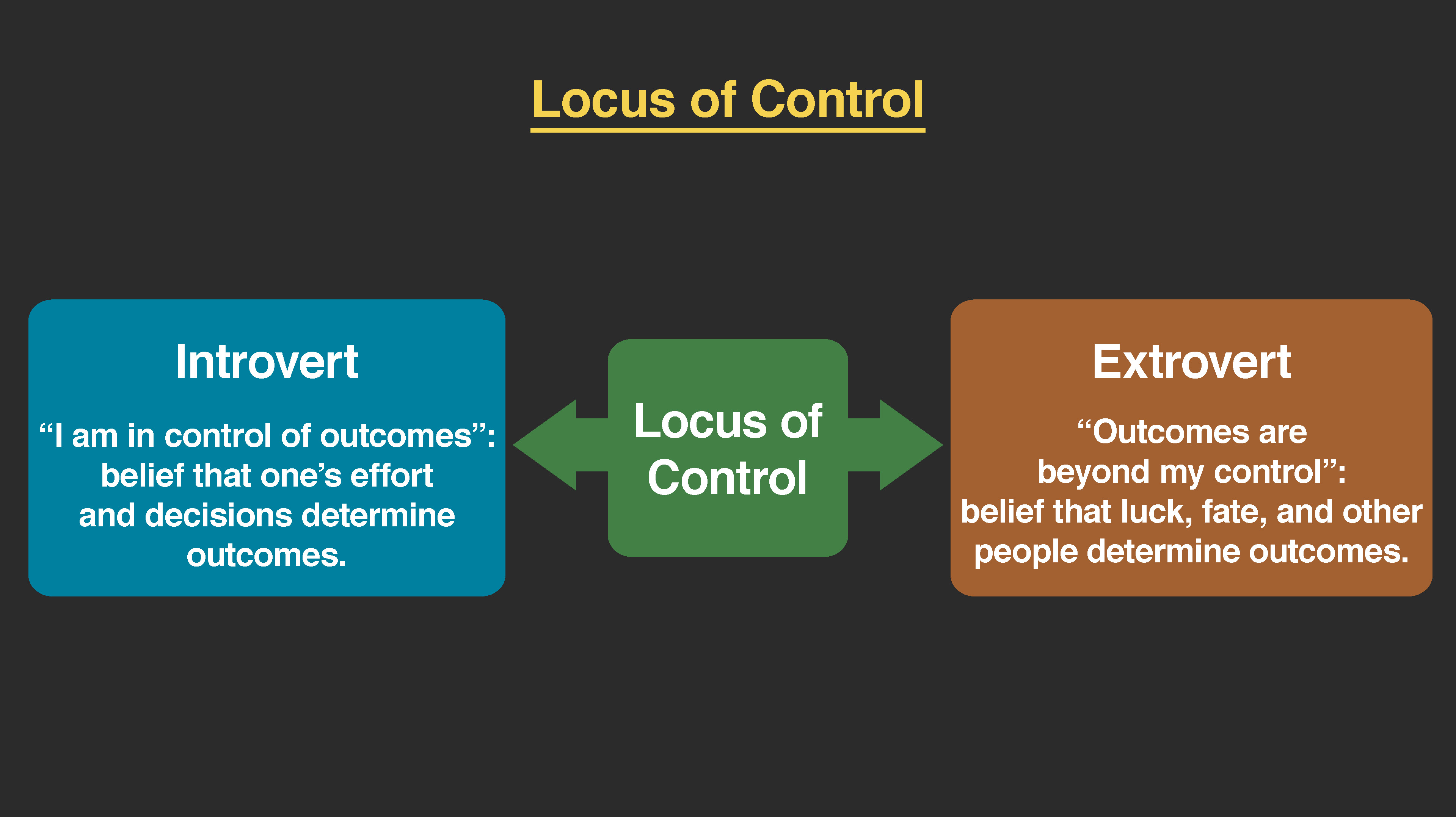

Julian Rotter proposed the concept of locus of control, another cognitive factor that affects learning and personality development. Distinct from self-efficacy, which involves our belief in our own abilities, locus of control refers to our beliefs about the power we have over our lives. In Rotter’s view, people possess either an internal or an external locus of control. Those of us with an internal locus of control (“internals”) tend to believe that most of our outcomes are the direct result of our efforts. Those of us with an external locus of control (“externals”) tend to believe that our outcomes are outside of our control. Externals see their lives as being controlled by other people, luck, or chance.

For example, you wanted to buy a car. You save some money, but you chose to go on an expensive vacation, went out to dinner frequently and bought a new computer and some sound equipment. You did not have enough money for a new car and were forced to buy a used car. If you possess an internal locus of control, you would most likely admit that you have to deal with the problems of used car ownership because who did not save, and you would resolve to forgo unnecessary purchases in favor of purchasing a better car next time. On the other hand, if you possess an external locus of control, you might blame the car as a “lemon” or blame the person who sold it to you, therefore, and keep spending money on unnecessary purchases. Researchers have found that people with an internal locus of control perform better academically, achieve more in their careers, are more independent, are healthier, are better able to cope and are less depressed than people who have an external locus of control.

Walter Mischel and the Person-Situation Debate

- Walter Mischel’s finding about personality

- The Marshmallow Test

- Self-regulation as will power

- Children’s goals in the Marshmallow Test

- Longitudinal research in the Marshmallow Test

- Person-situation debate

- Cognitive processes in the person-situation debate

Section Focus Question:

How did Walter Mischel research and resolve the person-situation debate?

Key Terms:

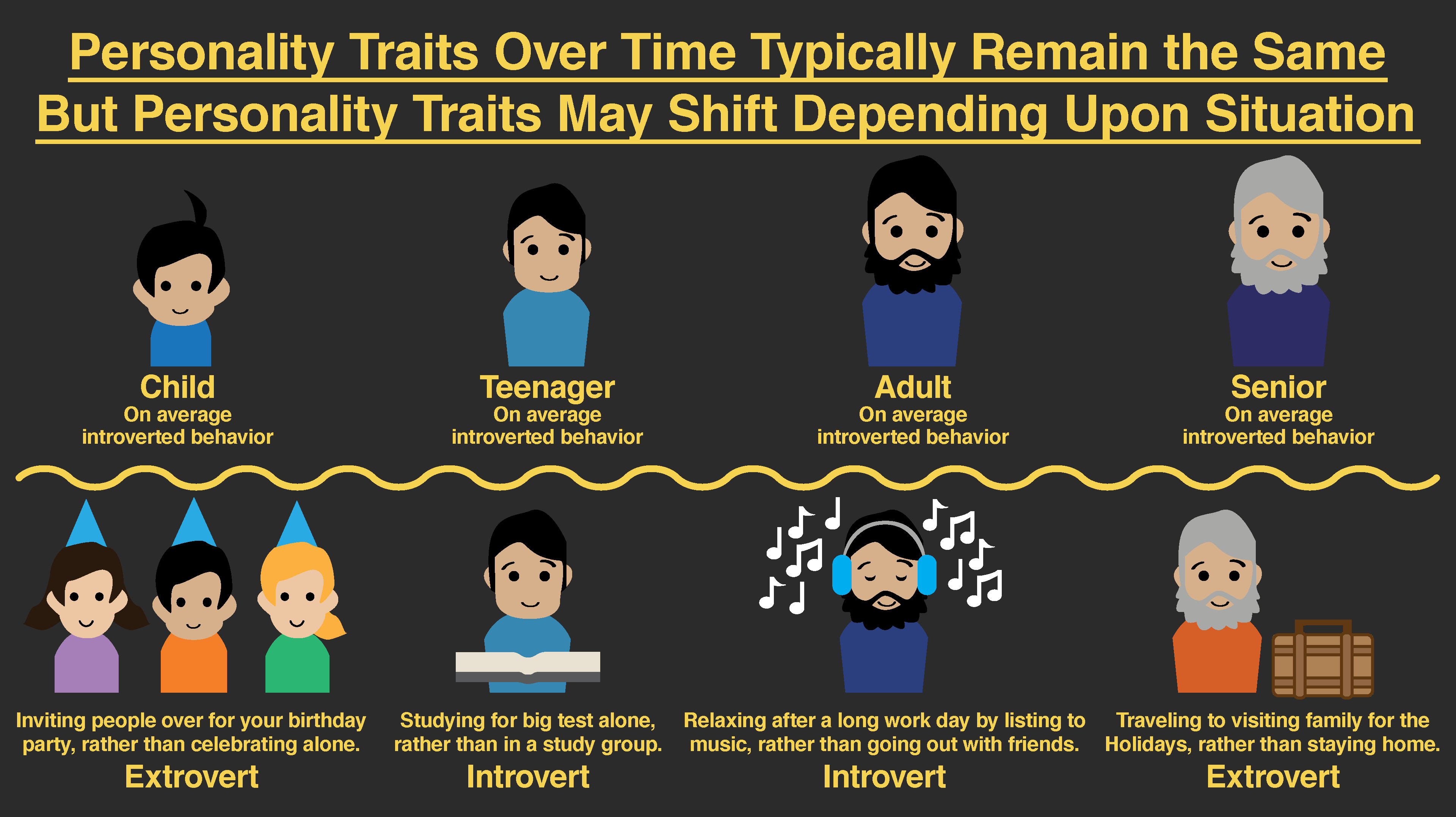

Walter Mischel was a student of Julian Rotter and a colleague of Albert Bandura. Mischel surveyed several decades of empirical psychological literature regarding trait prediction of behavior, and his conclusion shook the foundations of personality psychology. Mischel found that the data did not support the central principle of the field — a person’s personality traits are consistent across situations. His report triggered a decades-long period of self-examination among personality psychologists, known as the person-situation debate.

Mischel suggested that perhaps we were looking for consistency in the wrong places. He found that although behavior was inconsistent across different situations, it was much more consistent within situations — so that a person’s behavior in one situation would likely be repeated in a similar one. And behavior is consistent in equivalent situations across time. He demonstrated this observation in his famous Marshmallow Test with very young children, which explored the role of self-regulation in the development of personality. Self-regulation is also known as willpower. When we talk about willpower, we tend to think of it as the ability to delay gratification. In the case of the children and the marshmallows, could they delay gratification and refrain from eating the marshmallow set in front of them for a period of time, in order to get another marshmallow.

What Mischel and his team found was that young children differ in their degree of self-control. Mischel and his colleagues continued to follow this group of preschoolers through high school, and what do you think they discovered? The children who had more self-control in preschool (the ones who waited for the bigger reward) were more successful in high school. They had higher SAT scores, had positive peer relationships and were less likely to have substance abuse issues; as adults, they also had more stable marriages. On the other hand, those children who had poor self-control in preschool (the ones who grabbed the one marshmallow) were not as successful in high school, and they were found to have academic and behavioral problems.

Today, the debate is mostly resolved, and most psychologists consider both the situation and personal factors in understanding behavior. For Mischel, people are situation processors. The children in the marshmallow test each processed, or interpreted, the rewards structure of that situation in their own way. Mischel’s approach to personality stresses the importance of both the situation and the way the person perceives the situation. Instead of behavior being determined by the situation, people use cognitive processes to interpret the situation and then behave in accordance with that interpretation.