Vietnam and the 1960s

Note to students: The best preparation for taking the reading quiz is to pay close attention to the key terms as you read. Each question in the question banks is directly linked to these key terms and phrases.

Chapter Focus Question:

What was the impact of the Vietnam War on America and the world?

- Ngo Dinh Diem and a Buddhist monk's immolation

- US support of Ngo Dinh Diem and his popularity

- Purpose of the National Liberation Front

- Vietnam War and American troops

- Definition of the "domino theory"

- "Germany first" policy and US entrance into WWII

- Vietcong war tactics

- Assassination of President Diem

Section Focus Question:

What was the conflict between nationalist and Communist forces in North Vietnam and the French- and American-supported South Vietnam during and after WWII?

Kery Terms:

The Vietnam War and its surrounding circumstances are among the most important events in the 20th century. The conflict redefined much of the United States’ internal politics and self-image. In many ways, America’s involvement in Vietnam rattled the consensus politics of the 1950s and was a major driving force in Counterculture and reaction. Further effects rattled the world and helped spark a number of other conflicts and protest movements. Much of American history since has dealt with the complex legacy of the war in Southeast Asia.

Origins of the Vietnam War

The conflict in Vietnam was another example in the decades-long process of decolonization of much of Europe and Africa. Former imperial powers like France, Britain, and Portugal oversaw a number of turnovers to native peoples; some voluntary and others less so. Vietnam’s case was more complicated due to the French colony’s invasion and occupation by Japan in the Second World War.

Local forces led a sharp pushback against Japanese authority. In many ways, the occupation of 1940-45 created a national identity of resistance. Vietnam and wider French Indochina provided key similarities and differences to other states occupied by Imperial Japan.

Much of Vietnam’s society split on the reaction to the Japanese invasion. Some welcomed France’s abrupt exit while many others believed Japanese occupation was more brutal than that of the West. In particular, local militant groups including the Viet Minh led by Ho Chi Minh (1890-1969) remained a major foe of the Japanese efforts. Japan was careful to create an aura of continuation from the Vichy French forces. This ended in early 1945 as Japan sacked any remaining vestiges of French administration and colonial presence and replaced it with a puppet government under Emperor Bao Dai (1913-1997). This allowed a rapid rise of resistance fighters such as the Viet Minh. By the end of 1945, Ho’s forces controlled much of northwestern Vietnam. The Viet Minh expanded into other portions of the country, rapidly gaining in numbers and credibility.

By the end of the war, Ho Chi Minh emerged as a central figure to many Vietnamese. After travels to France, the United States, and Britain, Ho joined a variety of left-wing and socialist movements. Ho’s organization pushed for self-government of Vietnam at the Versaille peace talks but was not considered by the Allied Powers. However, Ho’s stature grew and traveled to the newly formed Soviet Union and aided Chinese Communists before returning to Vietnam in 1941.

In the aftermath of the Japanese occupation, Ho played a shrewd game against other Vietnamese factions. By the end of the 1940s, the Communists emerged as the primary representative of Vietnamese political life. However, France would not grant independence to the fledgling movement, soon to be the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. Ho met with Soviet and Chinese leaders Josef Stalin and Mao Zedong, respectively. The Communist dictators pledged early support to Ho’s movement.

France’s recalcitrance was both a burden and opportunity for Ho. He served as president and prime minister of the People’s Republic, commonly referred to as North Vietnam. French forces battled the Vietnamese during this first phase of the Vietnam War from 1946-54. The French often found themselves unable to adapt to a new style of warfare after the exhausting experience of the Second World War. By 1954 Vietnamese forces sharply defeated the French at the fortress of Dien Bien Phu. With the war seemingly unwinnable, France began its withdrawal from the country.

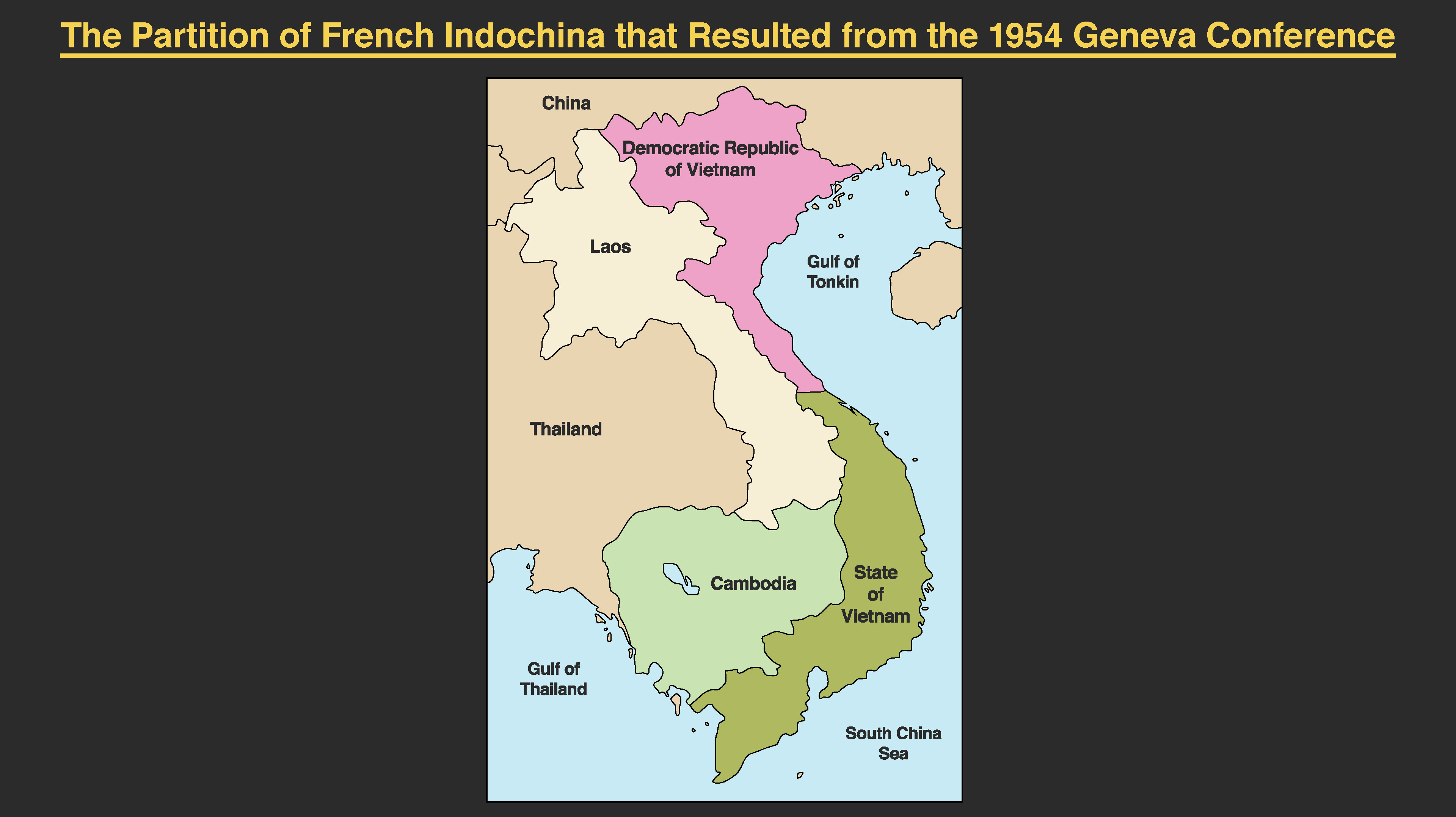

The Viet Minh and France signed the 1954 Geneva Accords, which effectively split the country in two, with the DRV dominating the north from Hanoi and the soon-Republic of Vietnam governing the south from Saigon. From this point on the United States became more involved in the situation especially after an effort for nationwide elections collapsed.

Vietnam’s changing efforts came during an interesting time for the United States. The expansion of Soviet power in Eastern Europe and beyond led to sharper responses from the West. Communist victory in China (1949) and the Korean War (1950-53) further pushed the concept of Containment and the emerging Domino Theory. North Vietnam’s aggressive actions included reprisals against landowners and an invasion of Laos in 1958-59, which led to the supply system known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

Early American Involvement

With Vietnam divided along the 17th parallel, the United States quickly became more involved as the 1950s continued. South Vietnamese dictator Ngo Dinh Diem (1901-63) was a staunch Catholic and anti-communist. His harsh repression of political and religious groups bred contempt among many non-communists in the country. Public order was difficult to maintain, especially after 1960 as the North sponsored the National Liberation Front, better known as the Viet Cong. Under President Dwight Eisenhower (1890-1969) the United States deployed hundreds of military advisors to South Vietnam to train local forces.

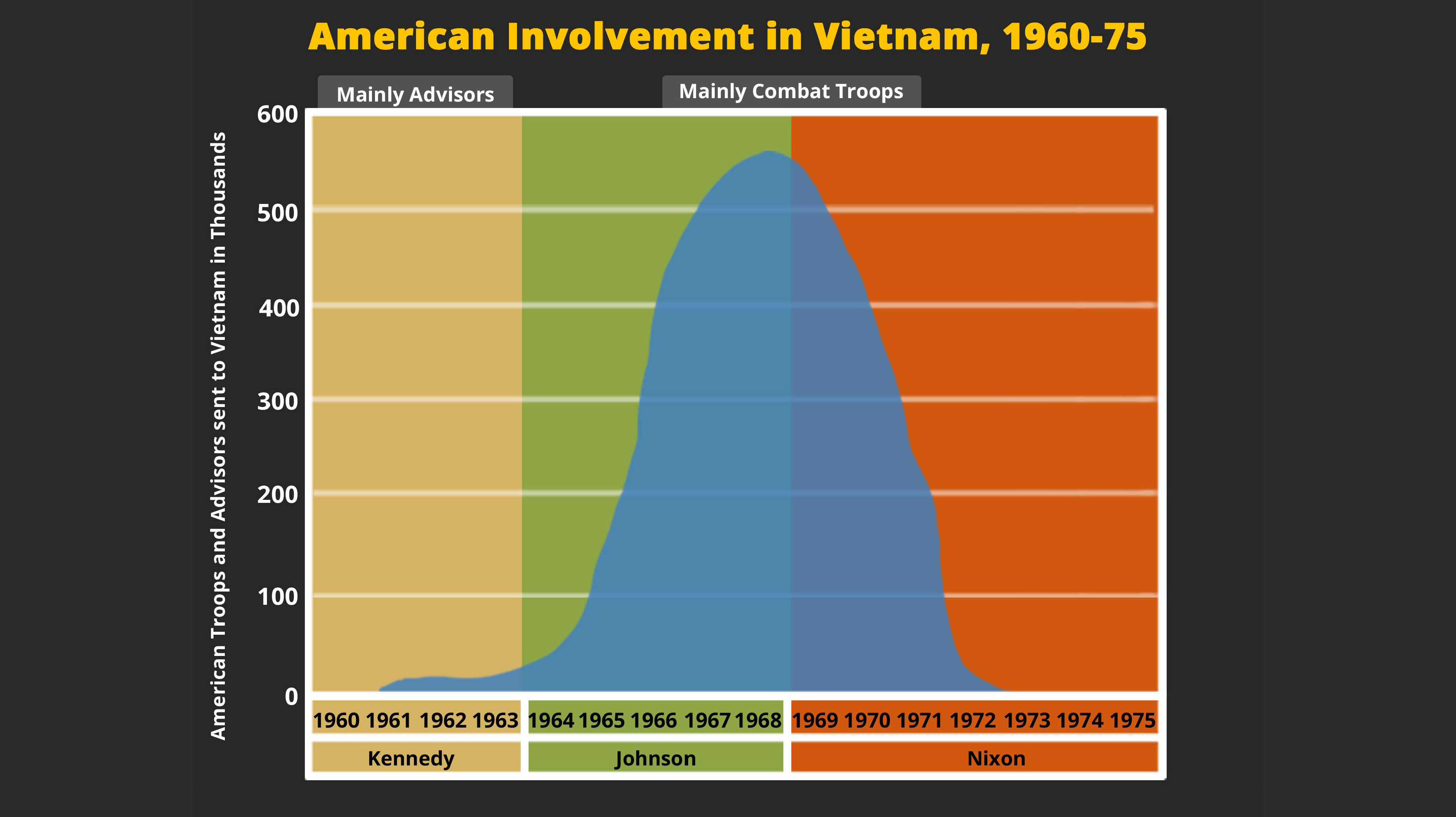

John F. Kennedy (1917-1963) won the 1960 presidential election bringing about a major change in policy. Outgoing President Eisenhower warned Kennedy about escalating issues in Indochina. The Kennedy Administration staunchly backed Diem’s regime at first, including an increase of military advisors. By the time of Kennedy’s death in 1963, this number increased to over 16,000. However, rebel attacks continued while South Vietnam’s government appeared paralyzed.

As the number of American forces increased in the country, tactics changed as well. South Vietnam and the United States forces instituted the Strategic Hamlet Program, which relocated thousands of peasants into separate military-style camps. This program did not achieve its goals to separate the rural population from the Communists. As the conflict continued and South Vietnam’s military and government struggled under pressure, the Kennedy Administration focused on Diem’s leadership. Protests by Buddhists continued apace and violence against religious groups sharpened through paramilitary and government actions. The American government split on the prospect of removing Diem from power, with the decision finally in President Kennedy’s hands. Vietnamese generals in contact with the CIA overthrew Diem on November 2, 1963. Instead of ending the violence, it accelerated, and guerilla activities increased.

Following President Kennedy’s death in November 1963, President Lyndon Johnson (1908-73) rapidly escalated American involvement in the war. South Vietnam’s government remained disorganized and was beset by another coup in January 1964.

Much of the reason for the escalation dates back to the Gulf of Tonkin Incident. On August 2, 1964, the U.S.S. Maddox fired upon several North Vietnamese torpedo boats which were following the American vessel. A similar incident was reported on August 4 between the Maddox and the U.S.S. Turner Joy. Historians still debate whether or not the North Vietnamese fired on American vessels or whether the Johnson Administration lied to Congress and the public. Regardless, the incident led to Operation Pierce Arrow, a bombing campaign, and the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution on August 7, 1964. This act of Congress gave President Johnson a free hand to wage war in and around Vietnam.

Early in 1965, the United States heavily increased bombing in North Vietnam. In March of the same year, the first American combat forces deployed to South Vietnam. By the end of the year, almost 200,000 American forces were in the country.

As American involvement increased, many of the truisms of U.S. military held since the Second World War changed rapidly. Viet Cong guerrilla tactics demoralized the South Vietnamese and damaged the American forces. Under the leadership of General William Westmoreland (1914-2005) direct American military involvement sharply increased. In addition, American allies including South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand sent troops to South Vietnam.

A Full-Blown War

- Rolling Thunder bombing campaign

- Gulf of Tonkin incident and US involvement

- Lyndon B Johnson and Vietnam

- Students for a Democratic Society and Vietnam summer

- Vietnam protests and civil rights tactics

- Tet Offensive and military success

- Lyndon B Johnson and the 1964 election

Section Focus Question:

How did American support for the Vietnamese War collapse and what did Nixon and the Democratic Congress do to bring it to an end?

Key Terms:

American troop levels continued to increase during the Johnson Administration. The Tet Offensive proved to be a major shift in the conflict on either side. On January 30, 1968, North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces broke the traditional truce surrounding the holiday Tet. Communist forces numbering over 80,000 attacked over 100 cities in South Vietnam. Perhaps the most telling visuals for Americans back home was a desperate firefight on the U.S. Embassy in Saigon.

The Tet Offensive was a tactical disaster for North Vietnam. It lost over 30,000 conventional and guerrilla forces and decimated much of the North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong’s organization. However, it proved to be a strategic success and a major component of the “Television War” horrifying Americans watching the nightly news. Over 1,000 Americans were dead across Vietnam, and meanwhile, public doubts about the war grew. By May 1968 Johnson approved peace talks between the US and North Vietnam to be held in Paris. These dragged on for months to no avail. In 1968, American troop numbers peaked in the country at over a half million. This was perhaps the height of American emotional trauma.

The situation rapidly destroyed Johnson’s political career. Originally entertaining a second full term in 1968, Johnson’s policy in Vietnam led to a yawning “credibility gap” between the reality on the ground and casualty figures. Johnson bowed to protest and internal pressure and dropped out of the 1968 race. Former Vice President Richard Nixon (1913-94) won the spirited contest. Nixon’s victory was due, in part, to his vows to reduce American involvement in Vietnam. American troop levels began declining as he took office. Nixon vowed “Vietnamization” and training of local forces. American tactics changed, as well. U.S. and South Vietnamese forces began more aggressive anti-insurgency measures. In addition, Nixon opened relations with the People’s Republic of China in 1972, splitting the two major communist blocs further.

Despite declining American troop numbers and casualties, the war escalated in other ways. In 1970, Prince Norodom Sihanouk of Cambodia (1922-2012) was overthrown by a pro-U.S. government. North Vietnam invaded Cambodia later that year. The United States and South Vietnam retaliated with its own incursion. American bombers carried out massive bombing runs on North Vietnamese forces and supply lines in the country.

These actions caused considerable dissent in the United States. Anti-war protests, declining with the smaller American presence in Southeast Asia, again spiked. Protesters at Kent State University at Ohio were victims of one of the most recognizable moments of the period. National Guardsmen opened fire on the crowd, killing four students and wounding nine. Four million students marched across the country in response to the killings. While the protests did not stop the American involvement in Cambodia, dissent against the war spiked.

In addition, South Vietnamese efforts to prevent communist activities in neighboring Laos were also a disaster. The Republic of Vietnam led a 1971 incursion into Laos to diminish guerillas’ access to the Ho Chi Minh Trail, which ended in sound defeat.

Decline of the Conflict

Nixon’s strategy of Vietnamization continued on track to mixed results. The number of American forces in the region continued to decline, falling below 200,000 in 1971. The South Vietnamese army grew in size but with limited capabilities. American airpower continued apace as a major support for the South’s forces.

The drawdown coincided with several major American domestic political events. The largest was the 1972 election. President Nixon ran on a campaign he would later refer to as “peace with honor.” His administration continued talks with the North Vietnamese government. The negotiations between National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger (1923-) and diplomat Le Duc Tho (1911-90) would eventually lead to 1973’s Paris Peace Accords. Opposing Nixon was Democrat George McGovern (1922-2012), who ran on a platform of immediate withdrawal. A month before the November contest, the United States and North Vietnam reached a tentative ceasefire agreement. Nixon’s victory was overwhelming, winning 49 of 50 states and over 60 percent of the vote.

North Vietnam leaked the contents of the diplomatic agreement after South Vietnam requested changes. President Nixon responded with Operation Linebacker II, a massive bombing campaign which lasted 11 days in December 1973. This move destroyed much of North Vietnam’s ability to conduct the war. The president also threatened to sign the agreement without South Vietnam if its government did not accept the terms. The following month, on January 27, 1973, the United States and both sides in Vietnam signed the Paris Peace Accords. The Accords called for a cease-fire and a withdrawal of American combat troops. Both sides agreed to release prisoners of war and to respect South Vietnam’s territory. The United States promised to replace material for South Vietnam if needed. The agreement also called for elections in both North and South and an eventual reunification of the country. Both Kissinger and Tho received the Nobel Peace Prize for their efforts.

Despite the agreement in Paris, the end of the Vietnam War did not proceed according to the Accords. The United States removed its final combat forces to the country and left a significant amount of military equipment for their allies. North Vietnamese forces and guerrillas remained in parts of South Vietnam. Instead of causing a collapse of South Vietnam, many of the guerrillas were pushed out of the Republic of Vietnam by local forces.

While North Vietnamese attacks and planning for a full assault continued, American ability and willingness to continue the war was over. President Nixon resigned the White House in August 1974 due to the Watergate scandal and was replaced with Gerald Ford (1913-2006). Between Democrats’ control of Congress and Ford’s newness, little aid was forthcoming to the South Vietnamese. Congress reduced aid to South Vietnam and sharply cut military operations in the region at a time that the Republic of Vietnam was in severe recession. A North Vietnamese offensive in late 1974 and early 1975 showed that the United States was in no position to return in any significant way. President Ford requested aid and supplies for the Republic, but Congress rejected his pleas.

Despite numerical advantages in military hardware, South Vietnam remained at a severe disadvantage. Morale collapsed as American aid ended and North Vietnamese victories seized more territory. By April 1975, North Vietnamese troops were on the doorstep of Saigon. President Thieu resigned from office and fled the country. On April 29, 1975 North Vietnamese forces seized Saigon, effectively ending the war.

Cultural and Political Effects

- Definition of Triangular Diplomacy

- George Wallace and discrimination

- Nixon administration accomplishments

- Watergate and Nixon's resignation

- Break of the "Cold War consensus"

- Content of the Pentagon Papers

- President Nixon 1968 election promise

- Issues that divided the Democratic Party in 1968

- Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers

Section Focus Question:

How did the war delineate a youth culture that influenced national and world events?

Key Terms:

The physical and political effects of the conflicts in Southeast Asia garnered most of the headlines but there was an unmistakable, simultaneous shift in the culture of the United States. The rationale and conduct of American involvement bred a number of reactions, often resistance and cynicism. Youth culture and an emerging counterculture grew as the war and the draft continued. A reaction also emerged, perhaps best exemplified by President Nixon’s November 1969 Silent Majority speech to the nation.

The anti-Vietnam War movement was perhaps the most extensive in American history. The anti-war movement borrowed from multiple strands in society, allowing it to grow in a unique manner. One powerful impetus was the large Baby Boom generation, born in the years after the Second World War. The young population formed the backbone of public protest against the conflict. Many of the protesters resented the draft that sent so many of their number to the jungles of Southeast Asia. Some of the more famous scenes of the era include young men burning their draft cards publicly.

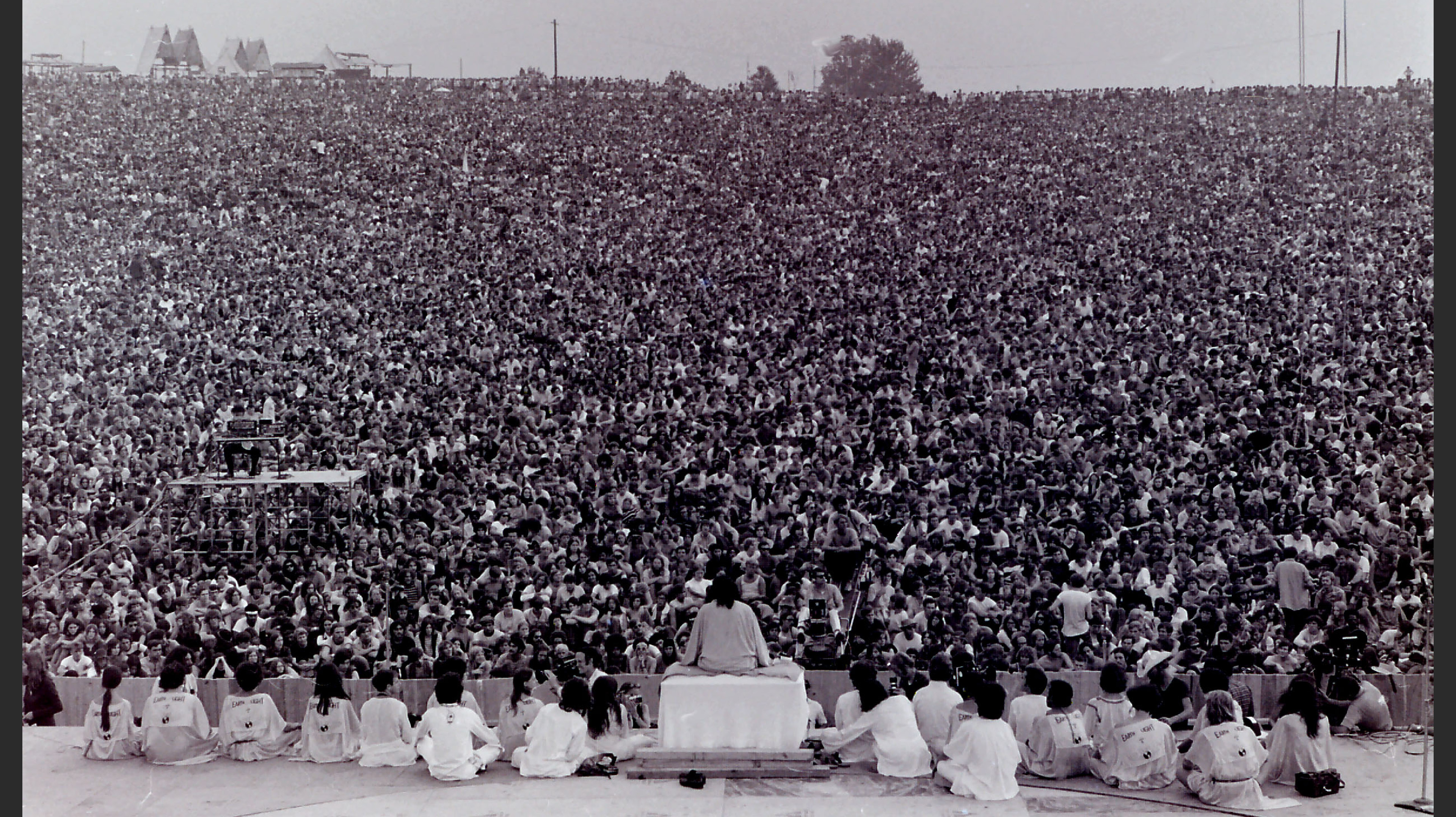

The anti-war effort also dovetailed with the nascent Counterculture in the United States and beyond. Many of the protesters were also members of the rapid cultural changes, including the rise of hippies and opponents of the American version of capitalist democracy. Opposition to the war as a common cause accelerated hippies’ communes, protest music, poetry, and 1969’s Woodstock music festival, which drew over 400,000 young people.

The crescendo of both movements came together in the protests around the Democratic Party’s convention in Chicago in 1968. Riots by the protesters were met with a crackdown by Chicago police. The messy violence outside the convention and the obvious split in the Democratic Party itself contributed to Republican Richard Nixon’s victory over Democratic nominee Hubert Humphrey (1911-78).

Despite the vociferous outcry of anti-war protests, there was a significant pushback. Many Americans ended their support of the conflict after the 1968 Tet Offensive yet did not align themselves with the anti-draft or pro-North Vietnam tenor of some of the protests. Part of this is seen in the large shift toward Richard Nixon’s 1968 Presidential campaign and during his administration. Many World War II veterans, union employees, and working class members swung their support towards Nixon’s gradual withdrawal and “law and order” approach. By the time of Nixon’s Silent Majority speech many geographic and demographic segments of the nation stood behind his approach. The end of the draft also severely reduced the number and intensity of the anti-war protests. By the 1972 election, Nixon actually carried the youth vote over George McGovern.

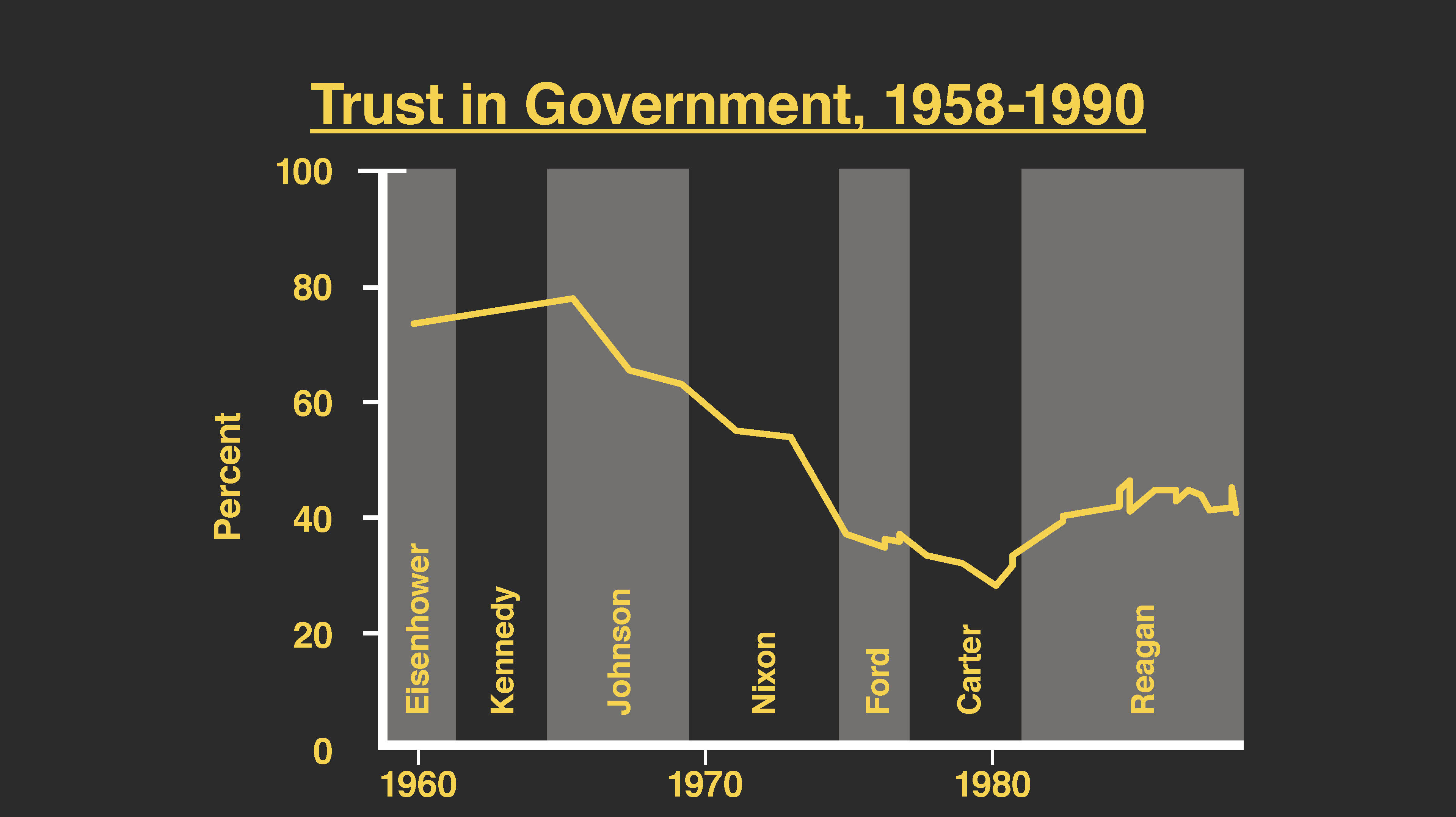

The Gulf of Tonkin incident, President Johnson’s justification for American involvement in Vietnam, and the course of the war deeply harmed faith in the federal government. These, combined with a number of scandals such as Watergate and missteps of the Carter Administration changed the way Americans of every demographic saw Washington’s power. Many in Congress gave Johnson the benefit of the doubt surrounding the Tonkin Resolution and the initial deployment of combat troops. Over time, more and more Congressional leaders and other public figures spoke out against the war.

Furthermore, President Nixon’s oversight of the conflict further bred skepticism. America’s involvement in Laos and Cambodia deeply countered stated goals of transparency in the region. One of the prime examples is the conflict over the Pentagon Papers. In 1971 the New York Times published a Department of Defense history of American involvement in Vietnam up to 1967. The papers discussed the Johnson Administration’s movement toward intervention in the conflict, bombing raids in Cambodia and Laos, and other elements not released to the general public. The Nixon Administration attempted to prosecute the Times' author, Daniel Ellsberg, claiming he committed a felony for publishing classified documents. The charges were later dropped. The White House also pressured the Times to stop such publications, but was halted by the Supreme Court’s 6-3 decision in New York Times Co. v. United States. The case showed an important distinction of press freedom and changed public perception of succeeding administrations’ handling of the situation in Vietnam and beyond.

Through much of the Johnson and Nixon presidencies, media coverage of the conflict played an increasing role. Vietnam is commonly referred to in popular culture as the first “television war.” Families watched footage of the war on their televisions each night, adding a visceral and realistic backdrop to fighting thousands of miles from home. Increasing attention also led to discovery of war crimes. The My Lai Massacre on March 16, 1968 was the most prominent. U.S. army soldiers opened fire on civilians in My Lai, South Vietnam, killing between 300 and 500. News of the slayings were published in the Associated Press in November 1969, leading to a major investigation and courts-martial but only one conviction. Further investigations by the U.S. government and the press uncovered dozens of similar yet smaller incidents. Both North and South Vietnam carried out large-scale killings.

In the aftermath of the war, the ghosts of the conflict haunted American policymakers. Vietnam veteran and future Secretary of State Colin Powell crafted the later-termed “Powell Doctrine” as a reaction to American involvement in Southeast Asia. Elements of overwhelming conventional military force was also used in the 1991 Persian Gulf War. In the aftermath of the swift victory with minimal American casualties, President George H.W. Bush said, “by God, we've kicked the Vietnam syndrome once and for all." Vietnam veterans Bob Kerrey, John Kerry, and John McCain all sought the White House. McCain, in particular, had been imprisoned by the North Vietnamese for five years.

World Effects

The Vietnam War and the reaction to it also affected youth movements across the world. The United States was not alone in having a large population of young people born since the end of the Second World War. The protests and discontent in the United States acted as both a microcosm and an impetus of larger protests around the world.

The protests had far and wide effects with large-scale movements across both Eastern and Western Europe. The two largest examples were the uprisings in France and Czechoslovakia.

In the former, two months of protests from May to June 1968 shook French society to its core. A number of protests, often led by young people, enveloped the country, including opposition to traditional capitalism, the French government, and American foreign policy. During the protests, over 10 million took to the streets or participated in workers’ strikes. The general strike shut down the ability for President Charles de Gaulle (1890-1970) to act decisively. Police enforcement instead led to larger protests. At one point President de Gaulle fled to a military base and called for early parliamentary elections. While de Gaulle’s allies won these elections handily, the tumult of the protests weighed heavily on him personally and politically. He resigned the presidency the following year and died in 1970.

a List of Their Demands in the Background, June 1968

In the case of Czechoslovakia, moderate reforms initiated by First Secretary Alexander Dubcek (1921-92) sparked an invasion by the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact. Czech non-violence emerged against Soviet domination, and several major communist movements across the world opposed the invasion.

The end of American involvement also carried a number of major effects on Southeast Asia itself. The Khmer Rouge communist movement came to power in Cambodia, communists seized power in Laos, and threatened to do so in Thailand. In Cambodia’s case, the Khmer Rouge massacred millions of civilians and precipitated a North Vietnamese invasion in 1978. This led to a punitive yet short Chinese invasion of Vietnam in March 1979.

Further Reading

- William Thomas Allison, My Lai: An American Atrocity in the Vietnam War, (JHU Press, 2012).

- David Anderson, ed. The Columbia History of the Vietnam War, (Columbia University Press, 2010).

- Kieth Beattie, The Scar that Binds: American Culture and the Vietnam War, (NYU Press, 2000).

- George H.W. Bush, “Remarks to the American Legislative Exchange Council,” (March 1, 1991).

- Department of the Army, Report of the Department of the Army Review of the Preliminary Investigations into the My Lai Incident, (1970).

- Department of Defense Vietnam Task Force, Report of the Office of the Secretary of Defense Vietnam Task Force (colloquially known as the Pentagon Papers), (Washington, D.C.: Office of the Secretary of Defense, 1969).

- David E. Kaiser, American Tragedy: Kennedy, Johnson, and the Origins of the Vietnam War, (Harvard University Press, 2000).

- Henry Kissinger, Ending the Vietnam War: A history of America’s Involvement in and Extrication from the Vietnam War, (Simon and Schuster, 2003).

- Mark Atwood Lawrence, The Vietnam War: A Concise International History, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

- Guenter Lewy, America in Vietnam, (Oxford University Press, 1980).

- Fredrik Logevall, The Origins of the Vietnam War, (London: Routledge, 2001).

- Robert S. McNamara, James G. Blight, Robert K. Brigham, Thomas J. Biersteker, and Herbert Schandler, Argument Without End: In Search of Answers to the Vietnam Tragedy, (New York: PublicAffairs, 1999).

- Kelly Moore, “Political protest and institutional change: The anti-Vietnam War movement and American science.” How Social Movements Matter (1999): 97-118.

- Mark Moyar, Triumph Forsaken: The Vietnam War, 1954–1965, (Cambridge University Press, 2006). James E. Westheider, The Vietnam War, (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2007).

Matthew Avitabile is an adjunct lecturer at the State University of New York at Oneonta and Cobleskill. He earned a master’s in European history from the State University of New York at Albany in 2010. He specializes in late 19th- to early 20th-century European nationalism and geopolitics.