Atlantic Revolutions and Independence

Note to students: The best preparation for taking the reading quiz is to pay close attention to the key terms as you read. Each question in the question banks is directly linked to these key terms and phrases.

Chapter Focus Question:

What patterns and phases did the revolutions on both sides of the Atlantic take?

- Meaning of revolution

- Coups d’etat

- Age of Revolution

- Wars between French and British

- Kinds of civil wars

- Declarations

- Seven Years’ War

- Cost of colonization

- Royal Proclamation of 1763

- Neglect led to liberty in the colonies

- Patriots vs. Loyalists

- French support for the American Patriots

Section Focus Question:

What precipitated the American Revolution and how important was the role of the American Creole elite?

Key Terms:

Scholars have debated what the term “revolution” means for a couple of hundred years, particularly with regard to political events. The word comes from revolutio, which in Latin means “a turn around.” But some turnarounds are greater than others. A great revolution, such as the French and Haitian Revolutions, completely undoes the prior political power of the society and replaces it with people, usually from the lower ranks of society, who have not held power before. On the other hand, the American Revolution and the Wars of Independence in Latin America were coups d’etat, overthrows of the leadership of a country or in this case colony. Some members of the colonial elites who were of European background and born in the Americas, called Creoles, rebelled and battled the mother country for control and leadership of the colonies. In all cases in the Americas, the rebel Creole elites won. The fifty years from 1770 to 1824 were a period of more than a dozen of these two types of revolutionary struggles on both sides of the Atlantic, which is why this is called the Age of Revolution. There were a few themes that the Atlantic Revolutions share.

International Context

First, the revolts on each side of the Atlantic were definitely connected to one another. It has often been remarked that the European intellectual movement called the Enlightenment, which championed human and political rights, inspired rebel leaders across the Atlantic. But even more important for colonial rebels were the opportunities to break away from Europe that were made possible because of the titanic 18th-century struggle between Great Britain and France for mastery of Europe, first in the Seven Years’ War (1756-63) and then in the Napoleonic Wars (1803-16).

Civil War

Second, all the revolts were civil wars, pitting one faction against another. In France, it was a class struggle between the lower and upper classes. In Haiti, slaves revolted against their masters. In the cases of the Wars of Independence, the rebel Creoles had to battle their colonial compatriots who were loyal to the mother country as well as the European armies. Civil war was most pronounced in the American Revolution and the Wars of Independence in Mexico and Peru, where there were significant numbers of officials from the mother country.

The Leadership of the Creole Elite

Finally, the rebellions were not only opportunistic, none of the leaders had a plan for what would come next or what kind of society they wanted. Many of the declarations and manifestos of independence or human rights came months and years after the rebellions began. The documents were often cries for more justice and equity but not plans for a new way of governing. Rebel leaders often disagreed as to the type of government. Lofty ideas of liberty contested with parochial local interests that involved slavery, land, territorial claims, labor systems, and individuals’ rights to participate in governance. In the end, while there was much rhetoric about liberty and equality, none of the Atlantic Revolutions resulted in an actual democracy. It would take decades before the liberated societies evolved into something like democratic republics for all of the people living in them.

The American Revolution

Up to the mid 18th century, Great Britain hardly attended to its British North American colonies. If anything, the crown’s interests were more focused on its increasingly valuable island colonies in the Caribbean. But in the Seven Years’ War (1756-63), the British waged war with France around the world in the Philippines, India, the Caribbean, and Canada, with the western frontier of the thirteen British American colonies being a major theater of war. The British won victory after victory around the world in these contests including acquiring much of the French colonial lands east of the Mississippi River. They had invested the modern equivalent of millions of pounds in securing that frontier. After more than a century of neglect, British officials and officers returned to Great Britain impressed with the economic potential of the colonies. The British believed it was time for British Americans to become better integrated into the British economy and geopolitical interests of the empire.

The international context. While British Americans were quite proud of the empire’s victories in the war, they were less convinced that they had a role to play in securing those victories. But British leaders did not think it was fair that the colonies paid only one shilling of tax per capita to the empire, while British citizens paid 26 shillings per capita. Moreover, the imperial government needed more revenue to finance the national debt, which had soared from 73 million pounds before the war to 137 million pounds after the war. And more debt was mounting as the British had to station 10,000 troops to garrison the territories they had conquered from the French in North America. A particularly vexing issue was the disposition of those conquered lands. Land-hungry colonists wanted to head out west to survey, sell, and buy the land. Each encroachment into the new territories set off an Indian war that the British army had to quell with more and more soldiers. The crown established a Royal Proclamation of 1763, a treaty with the Native American groups that colonials would not cross the line to settle the new territories. The colonists naturally violated the treaty at every turn, creating tensions not only with the Native Americans but also British colonial officials and Parliament.

The leadership of the Creole elite. Victory in the Seven Years’ War had turned out to be a double-edged sword. On the other side, the British had grown too confidant of the power of their army and navy and could hardly imagine a rebel threat from the colonists. The removal of the French from North America had taken away the common enemy of the British officials and the colonists. They soon began to bicker with one another, particularly over a series of fees or indirect taxes that the British tried to impose after 1770. One must also remember that the years of neglect had allowed the colonists to begin to develop their own local governments, schools, churches, and other institutions. In the Americas, the Creole elite of the British colonies was probably the most effective home-grown leadership. One could even argue that American colonists participated more in self-government than those in the British Isles. A man had to have land to vote in elections at the time. Only one in four men in Britain had the vote, but at least half to two-thirds of British Americans had the franchise. Moreover, the colonies had no natural aristocracy. The elite was simply the wealthier and better educated among the colonists. Therefore, the colonies had as a matter of habit and course, a more democratic style to their political environment.

Civil war. But the elite was not united in support of independence. The rebels called themselves the Patriots and were about 40 percent of the population, while the Loyalists who wanted to stay in the empire represented about 25-30 percent of the colonial population. The battle between these two groups was brutal, particularly along the western frontier and particularly when it involved Native American allies. After the revolution, the Loyalists in many cases were forced to emigrate to Canada and the Caribbean. The war finally ended when the British public fatigued of the high cost of blood and treasure. But international circumstances again played a decisive role — the French navy came up from the Caribbean in support of General George Washington’s land troops, delivering a fatal blow to the British at Yorktown, forcing the British to sue for peace.

The French Revolution (1789-1799)

- France’s war debt from the American revolution

- Drought before the French Revolution

- Estates General

- Rhetoric of liberty

- Reign of Terror

- Estates General

- Thermidorian Reaction

- Napoleon Bonaparte

- Proportion of slave to free

- Issue of manumission and violence in Haiti

- Toussaint Louverture

- French recognition of Haitian independence

Section Focus Question:

How do the French and Haitian Revolutions compare?

Key Terms:

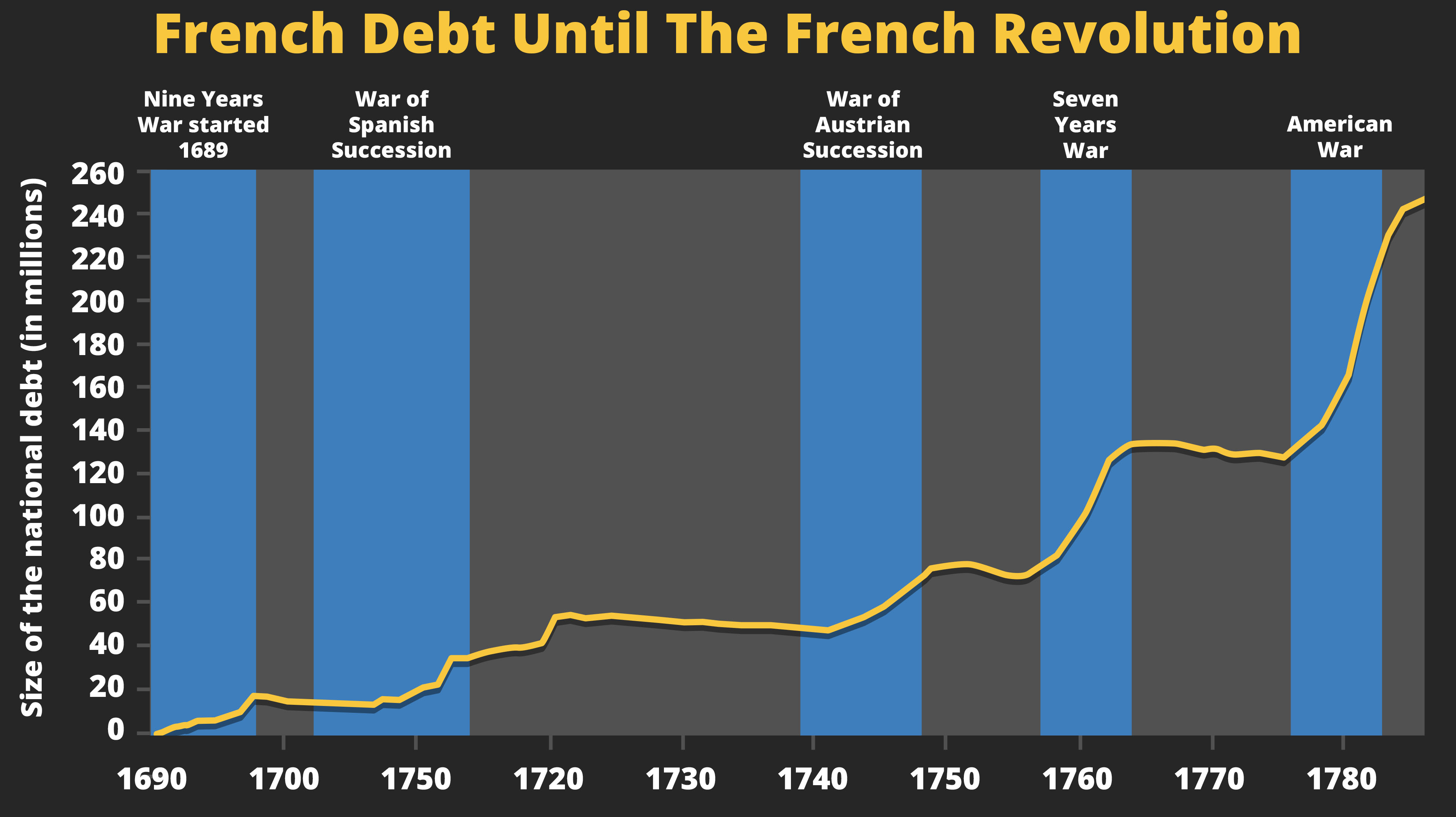

International context. Here again, events across the Atlantic helped set the stage for the French Revolution. The success of American revolutionary political ideas inspired the educated lower classes in France to throw off the yoke of feudal government of the French monarchy and aristocracy, often called the the ancien régime. But even more important, as with Great Britain, the military cost of helping the Americans in 1783 and the lingering debt of the Seven Years’ War forced the French crown to raise regressive taxes on its citizens, the poorer paying a higher rate than the wealthy and more privileged. Aggravating the situation was the fact that France suffered several years of drought in the 1780s and there was famine in the countryside, causing food shortages in the cities.

Problematic leadership. But most historians of the French revolution recognize that the rhetoric of liberty and equality swept up the people and provided them with governing aspirations for which they had no practical experience. The French government was a feudal system of monarchy, aristocracy, and clergy; the crown had long ago dismissed the old institution of the people, the French equivalent of Parliament called the Estates General. In the first phase of the revolution (1789), the crown was forced to reconvene the Estates General, which was dominated by representatives from the educated middle class — teachers, lawyers, shopkeepers, and low-ranking military officers — who were inspired by the Enlightenment ideas of liberty and equality but knew little of how to compromise their politics and organize a government. The result was a second phase (1790-94) called the Reign of Terror, in which political factions — from conservative to radical — began to execute political opponents; at least 15,000 and perhaps as many as 40,000 died. The factions were particularly radicalized by reports that conservatives and aristocrats abroad were encouraging the other crowns of Europe to attack France and restore the monarchy. This threat finally led to the imprisonment and execution of King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette.

Civil war averted and replaced with new imperialism. In the third phase, or the Thermidorian Reaction (1795-99), a moderately conservative executive council called the Directory took over the reigns of the state to restore order. But the committee was rife with corruption and autocratic figures. By 1799, one member of the committee, General Napoleon Bonaparte, organized a coup d’etat, and thus the fourth phase of the revolution, the Consulate, began leading to the dictatorship of Napoleon, and then Napoleon crowning himself as emperor in 1803. Of course, after a decade of failed civilian government, the people threw their support behind the institution and the man who delivered them their greatest success — the army. And the French armies were brilliant. They marched across Europe and into the countries of the Mediterranean destroying monarchies and spreading the ideas of the French revolution. But Napoleon and the French had simply replaced an oppressive monarchy with a dictatorship. The French Revolution’s greatest success was that it ended the credibility and stability of the European ancient regime; it did not establish the Enlightenment ideal of a democratic republic. Led by Great Britain, a coalition of crowns across Europe defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo, and France suffered through another 50 years of intermittent despotic monarchies and failed republics.

The Haitian Revolution

The International context. The Haitian Revolution is difficult to imagine without the French Revolution. Haiti is the western half of the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean. The Spanish conceded this territory to the French in 1697, who called it Saint-Dominique. The French colonized it with slaves and sugar plantations that had a reputation for being some of the most brutal in the New World; fully a third of imported slaves died within a few years. While 32,000 whites, or blancs, lived in Saint-Dominique, they were vastly outnumbered by the more than 500,000 slaves, most of whom were born in Africa and retained their African culture. There was also a small but important population of 25,000 free blacks and mulattos, or gens de coleur, many of whom owned slaves. Inspired by the revolutionary events in France in 1789, the gens de coleur began to agitate for more rights. For the next two years the French National Assembly debated both the rights of free blacks and mulattos and the issue of manumission of the slaves. In May 1791, they gave rights to the former but not manumission to the latter.

By August 1791, thousands of frustrated slaves rose in rebellion. Within weeks, the number of slaves who joined the revolt reached some 100,000. In the next two months, as the violence escalated, the slaves killed 4,000 whites and burned or destroyed 180 sugar plantations and coffee and indigo plantations. In September 1791, the surviving whites organized themselves and struck back, killing about 15,000 blacks in an orgy of revenge. Though demanding freedom from slavery, the rebels did not demand independence from France at this point, rightly calculating that the French government would grant them freedom in order to quell the black rebellion in 1794.

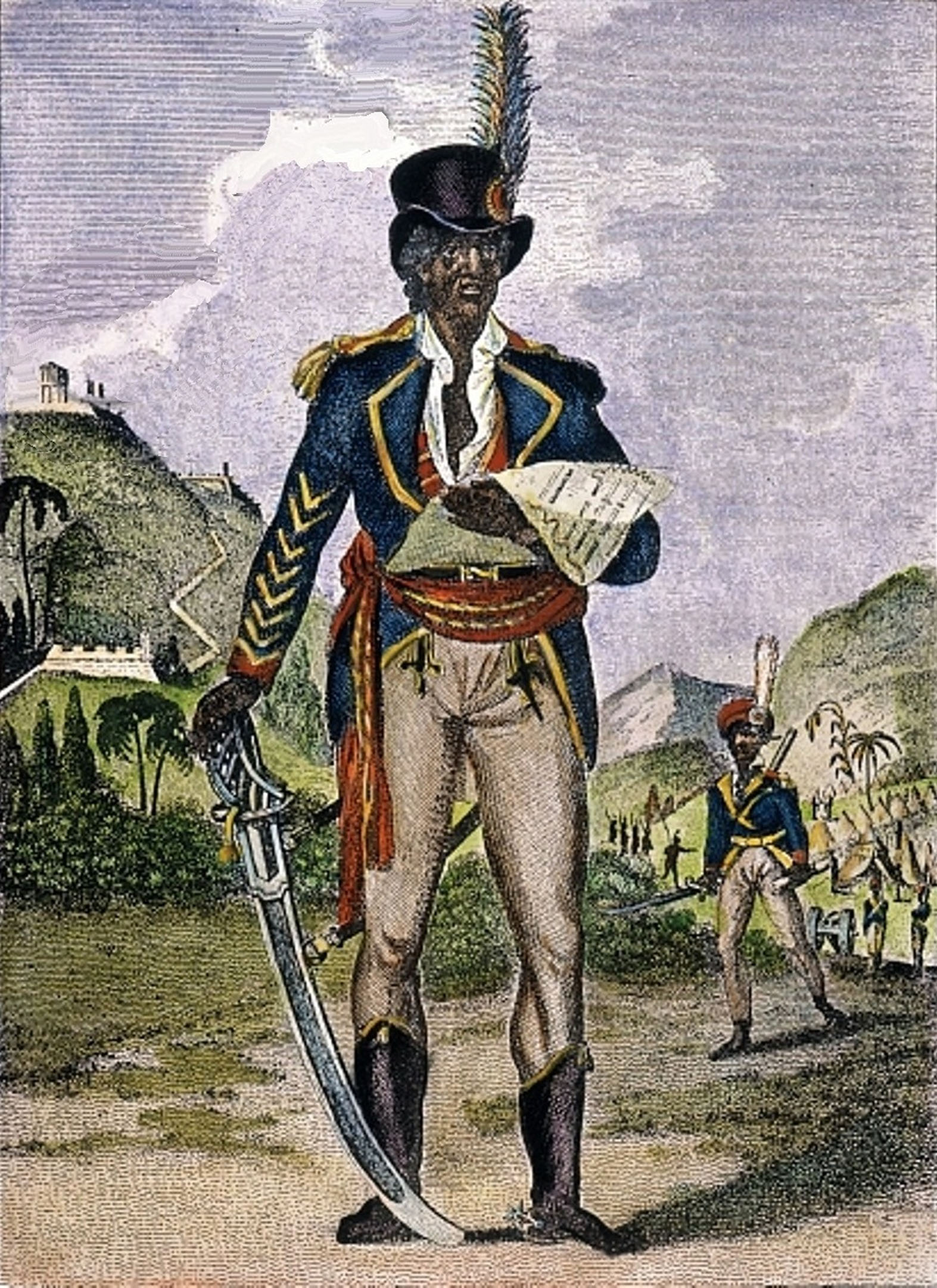

Leadership in the Creole elite. Since 1789, numerous mulatto and black leaders led factions of the revolt, fighting each other as much as the French. The most successful was Toussaint Louverture, a former slave, slaveholder, and a military leader. In the 1790s, he gradually gained control of the whole island from his various rivals and gave nominal allegiance to France while pursuing his own political and military designs. In May 1801 he named himself “governor-general for life.” This would prove to be the pattern with the new Haitian leaders. A military leader would consolidate power through conquest, become the dictator, and eventually become emperor, a plan Louverture had before he died. The homegrown leaders of Saint-Dominique and their formerly-slave citizens felt more acutely the aspirations of liberty and freedom than they understood the making and maintaining of a government of all the people.

When Napoleon Bonaparte consolidated his power in 1801, he attempted to restore the old regime, slavery, and European rule by sending an army to Saint-Domingue that included his own brother-in-law. Toussaint tried to arrange an armistice in May 1802 but ended up in a French prison, dying in April 1803. In his absence, his lieutenants, Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Henry Christophe led a black army against the French in 1802. They defeated the French commander and a large part of his army. Debilitated by yellow fever and malaria, the French withdrew from Saint-Dominique but maintained a small presence in the eastern part of the island until 1809.

Civil war. On January 1, 1804, the entire island was declared independent. Dessalines renamed the country Haiti from an older indigenous name. It was the first nation of former slaves in world history and the second independent republic in the Americas. Many European powers and their Caribbean surrogates ostracized Haiti, fearing the spread of slave revolts. More important, nearly the entire population was utterly destitute—a legacy of slavery that has continued to have a profound impact on Haitian history. Moreover, Haiti was plagued by factionalism. Regions of the island often would continue to break out in open revolt. The ”gens d’ coleur” refused to submit to the rule of former slaves-become-dictators (and emperors).

In October 1804 Dessalines assumed the title of Emperor Jacques I, but in October 1806 he was killed while trying to suppress a mulatto revolt, and Henry Christophe took control of the kingdom. Civil war then broke out between Christophe and Alexandre Sabès Pétion, who was based at Port-au-Prince in the south. Christophe, who declared himself King Henry I in 1811, managed to improve the country’s economy but at the cost of forcing former slaves to return to work on the plantations. In 1820 his soldiers mutinied, and he committed suicide. It was not until 1825 that France recognized Haiti’s independence, and then only in exchange for a large indemnity of 100 million francs.

The Wars of Independence in Latin America (1807-1824)

- Bourbon reforms

- Trouble alliance between Spain and France

- Juntas of Creole and peninsular elites

- Bolivar

- San Martin

- Iguala Plan

- Post-revolutionary governments

Section Focus Question:

What precipitated the wars of independence in Mexico and South America?

Key Terms:

After three centuries of colonial rule, independence came rather suddenly to most of Spanish and Portuguese America. Between 1808 and 1826 all of Latin America except the Spanish colonies of Cuba and Puerto Rico slipped out of the hands of the Iberian powers who had ruled the region since the conquest. The rapidity and timing of that dramatic change were the result of a combination of long-building tensions in colonial rule and a series of external events.

The international context. Even before the British in the 1770s began to integrate the thirteen colonies into the larger empire, the Spanish government instituted reforms in the 1740s.

Many Creoles felt Bourbon crown policy to be an unfair attack on their wealth, political power, and social status. Creoles reacted angrily against the crown’s preference for Spanish-born officials, peninsulars, in administrative positions. After hundreds of years of proven service to Spain, the Creole elites felt that the Bourbons were now treating them like a recently conquered nation. In cities throughout the region, Creole frustrations increasingly found expression in ideas derived from the Enlightenment. Still, these ideas were not, strictly speaking, causes of independence. Rather, European diplomatic and military events provided the final catalyst that turned Creole discontent into full-fledged movements for Latin American independence.

When the Spanish crown entered into an alliance with France in 1795, it pitted itself against England, the dominant sea power of the period, which used its naval forces to reduce and eventually cut communications between Spain and the Americas. In 1808 Napoleon turned on his Spanish allies and imprisoned both King Charles IV and his son Ferdinand. The Spanish political tradition centered on the figure of the monarch, yet, with Charles and Ferdinand removed from the scene, the hub of all political authority was missing. The Spanish in Spain tried to set up a government more or less in exile in southern Spain beyond the reach of the French army. While some Creole leaders came to Spain to join in the Cortes, or new Spanish government, they found that the peninsular Spaniards were not willing to given them the autonomy they wanted.

Interestingly, Spanish troubles had already led to Brazilian independence. In 1807 the Spanish king had granted passage through Spanish territory to Napoleon’s forces on their way to invade Portugal. The immediate effect of that concession was to send the Portuguese ruler, Prince Regent John, fleeing in British ships to Brazil. Arriving in Rio de Janeiro with some 15,000 officials, nobles, and other members of his court, John transformed the Brazilian colony into the administrative center of his empire.

Leadership in the Creole elite. During 1808–10, juntas, committees of temporary governance, emerged all across the Spanish colonies to rule in the name of the king. But the aspiring leaders were either groups of peninsulares or combinations of peninsulars and Creoles who did not always trust each other. In Mexico and Uruguay caretaker governments were the work of loyal peninsular Spaniards eager to head off Creole threats. In Chile, Venezuela, Columbia, and other colonies, by contrast, it was Creoles who controlled the provisional juntas. By 1810, however, the trend was clear. Without denouncing Ferdinand, Creoles throughout most of the region were moving toward the establishment of their own autonomous governments. By 1812 a British-Spanish insurrection and military expedition dislodged Napoleon from Spain. Ferdinand VII came back to power and sent Spanish troops to take back control of the colonies. Over the next decade and a half, Spanish Americans had to defend with arms their own movement toward independence.

Perhaps the most famous of these Creole military and independence leaders and heroes was Simon Bolivar of Venezuela, also called the Liberator. From Argentina proceeded another powerful force, this one directed by José de San Martín. After difficult conquests of their home regions, the two movements spread the cause of independence through other territories, finally meeting on the central Pacific coast. From there, troops under northern generals finally stamped out the last vestiges of loyalist resistance in Peru and Bolivia by 1826.

The independence of Mexico, like that of Peru, the other major central area of Spain’s American empire, came late. As was the case in Lima, Mexican cities had a powerful segment of Creoles and peninsular Spaniards whom the old imperial system had served well. Between 1808 and 1810, peninsulars had acted aggressively to preserve Spain’s power in the region by taking over the government. Nevertheless, homegrown independence movements emerged under two radical priests, the Creole Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla and the mestizo José María Morelos y Pavón. Each appealed directly to the indigenous and mestizo populace, which sufficiently frightened the Creoles in Mexico City into joining peninsulars to suppress the revolts.

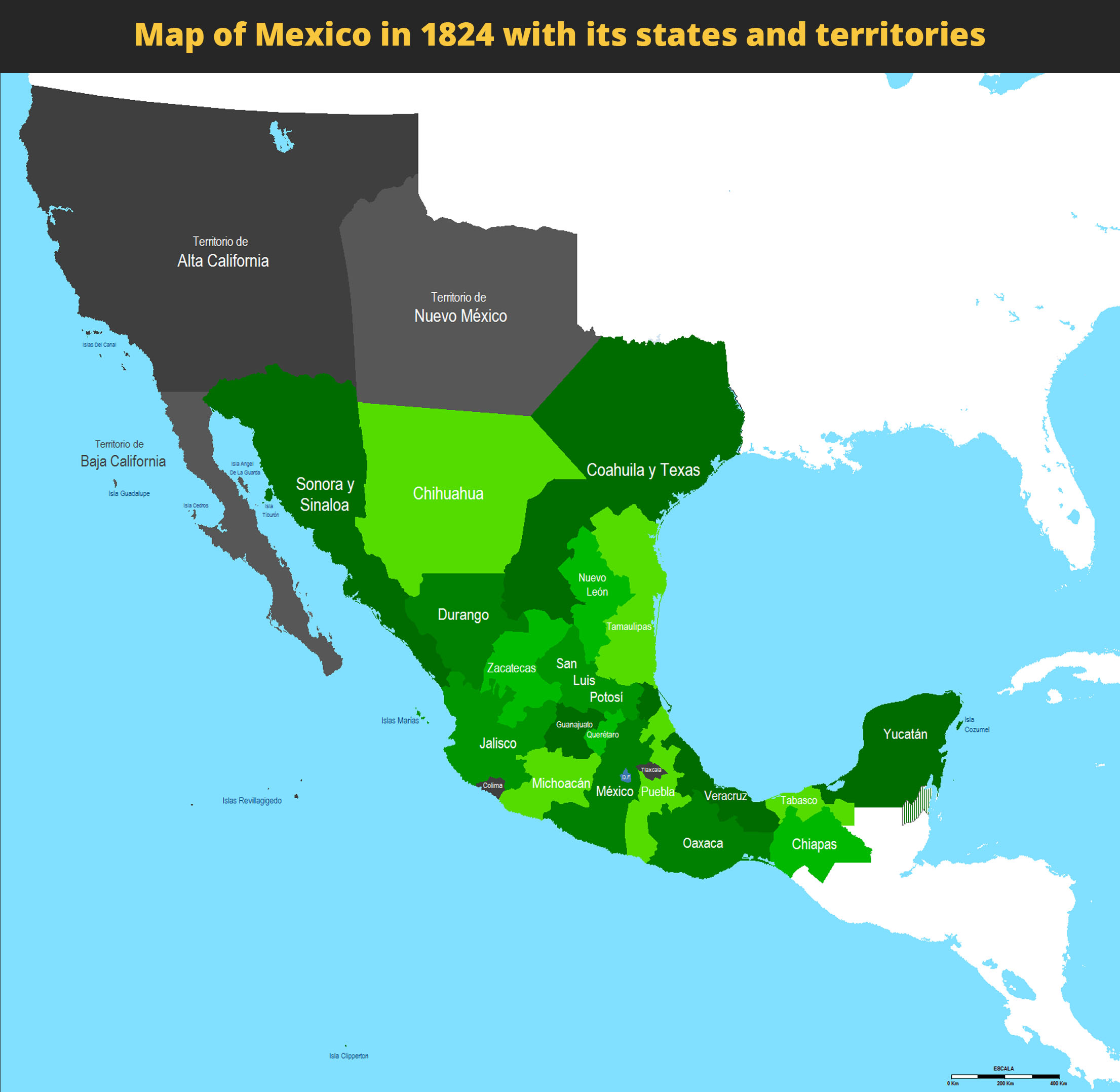

Final independence, in fact, was not the result of the efforts of Hidalgo, Morelos, or the forces that had made up their independence drive. It came instead as a conservative initiative led by military officers, merchants, and the Roman Catholic Church. Confident in their ability to keep popular forces in check, Creoles finally turned against Spanish rule in 1820–21. Two figures from the early rebellion played central roles in liberating Mexico. One, Vicente Guerrero, had been an insurgent chief; the other, Agustín de Iturbide, had been an officer in the campaign against the popular independence movement. The two came together behind an agreement known as the Iguala Plan. Centered on provisions of independence, respect for the church, and equality between Mexicans and peninsulars, the plan gained the support of many Creoles, Spaniards, and former rebels. Unfortunately, Iturbide tried to install himself as Agustín I, Emperor of Mexico. Guerreron joined another former insurgent Guadalupe Victoria and overthrew Iturbide, establishing a republic in 1824.

Civil wars. In all of the wars of independence there was a struggle between the peninsulars, the Creoles, and the popular masses, including indigenous people, slaves and free blacks. Civil war generally raged when two of the three banned together to fight the third. In Mexico it was the temporary alliance of Creoles and peninsulars against the indigenous, blacks, and poor whites. In Venezuela, Bolivar’s armies were led by both Creoles and some mulatto leaders. The troops included Creoles, free blacks, and some former slaves and indigenous people. They fought Spanish troops and loyalists. Creole elites generally emerged as the leaders of post colonial societies but even then most liberal leaders like Bolivar,expressed strong doubts about the capacity of his fellow Latin Americans for self-government. “Do not adopt the best system of government,” he wrote, “but the one most likely to succeed.” Thus, the type of republic that he eventually espoused was very much an oligarchic one, with socioeconomic and literacy qualifications for suffrage and with power centered in the hands of a strong executive. Across Latin America, independent republics formed that were consistent with colonial administrative centers and districts. Local Creoles in the major cities dominated and government was oligarchic in nature, not particularly enlightened and not democratic.