The West Looks East, Again

Note to students: The best preparation for taking the reading quiz is to pay close attention to the key terms as you read. Each question in the question banks is directly linked to these key terms and phrases.

Chapter Focus Question:

What were the experiences of European men and women who travelled to the East?

- European-Indian hybrid society

- Ludovico de Varthema

- Henry the Navigator

- Christopher Columbus and the western route to Asia

- Pedro Álvares Cabral

- Portuguese caravels

- Duarte Barbosa,

- Spread of Portuguese Empire

- Goa

Section Focus Question:

What did travels to the Levant and India reveal to Europeans?

Key Terms:

In 1506, after several years of exploring the Levant and parts of Asia before returning to Lisbon in 1508, the Bolognese traveler Ludovico de Varthema (ca 1470–1517) was surprised to discover two Milanese gunners living in Calicut, India. Their delight in meeting a fellow Italian was matched only by their sadness and desperation at being stuck halfway around the world. If they returned to Goa, they feared punishment from the Portuguese on whose ships they had sailed. Any attempt to leave Calicut risked the wrath of the local ruler, who closely guarded them in order to benefit from their ability to cast European weapons to fortify his city, presumably to avoid further onslaughts from the Portuguese during the first decade in which they established their presence in India.

After returning to Goa, Varthema was distressed to discover that the Portuguese pardon he obtained failed to save them from the surveillance and suspicion surrounding the movements of Europeans in Calicut, perhaps especially those employed for their expertise by the king. A household slave warned of their imminent departure, precipitating a riot in which they were killed. Varthema later purchased the freedom of the half-Indian son of one of the men and had him baptized. Young Ludovico died the following year. Such was the tenuous nature of the hybrid, partly European society forming in Asia after the arrival of Vasco da Gama in Calicut on May 20, 1498.

Varthema published his bestselling Itinerary in Florence in 1510, barely a decade after the Portuguese crossed the Indian Ocean. His remarkable voyage of 1504–08 emerged from the desire to see places “the least frequented by Venetians” and write about the experience of travel upon his return. The novelties he wished to see for himself did not belong to the New World, however. Varthema arrived in India shortly after the appointment of the first Portuguese viceroy in 1505. He left before the Portuguese completed their fort in Goa in 1510 to establish this important base of operations. He was an eyewitness to the birth of the Portuguese Empire, and a free agent who traveled with the Portuguese, but he was not beholden to them, making him one of the most interesting kinds of global travelers.

Sailing to the Indies

When the German gunner Hans Staden found employment on Portuguese ships in order “to see India,” he did not especially care whether this meant going east or west since this distinction was largely without a difference until well into the 16th century. Columbus sailed southwest from Seville in search of an alternate route to the Indies for his Spanish patrons, Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile, largely because Portuguese navigators were systematically making their way along the West African coast, establishing trading forts to secure their investments in this part of the world.

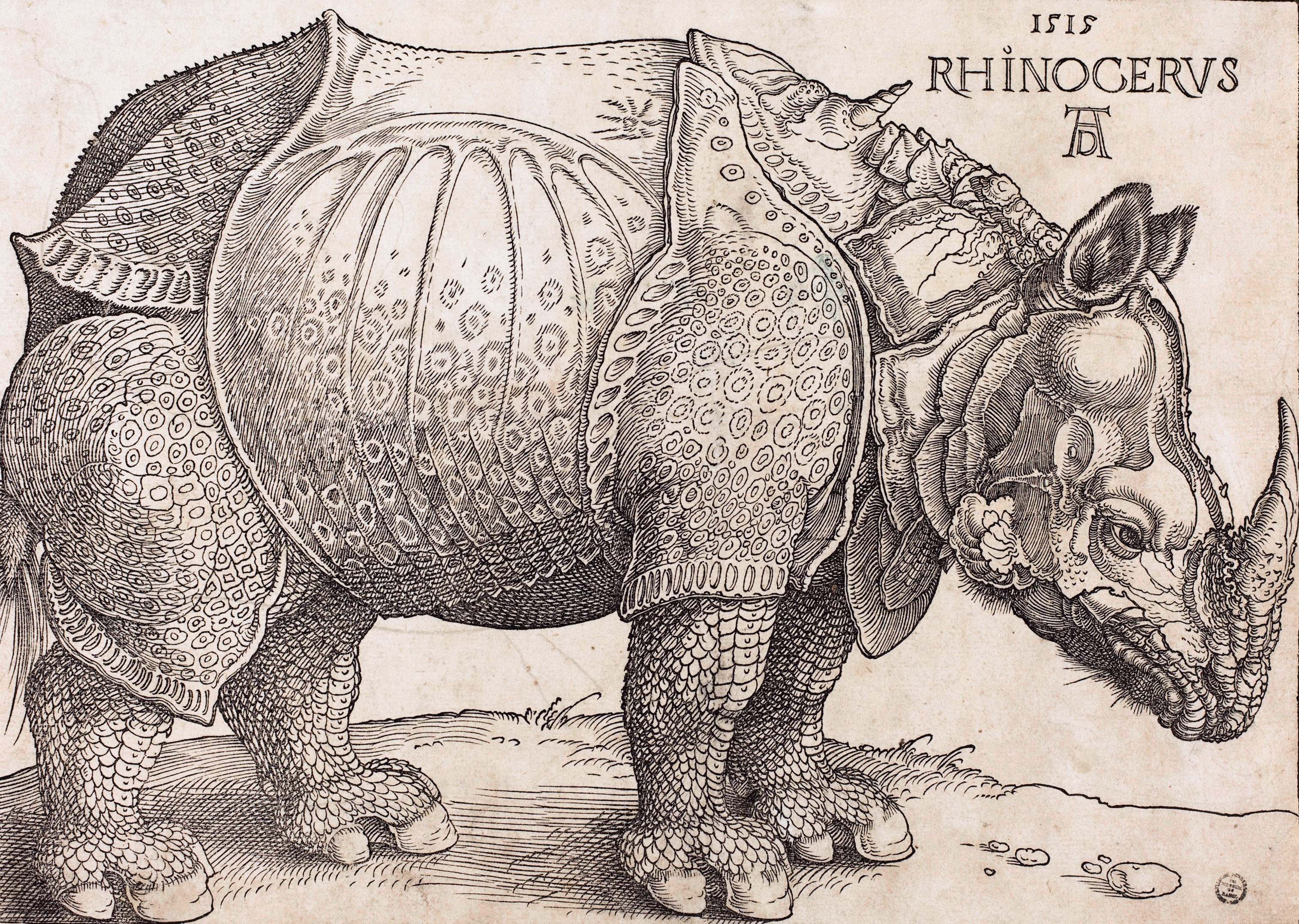

By 1481, Bartolomeu Dias arrived at the Cape, making the prospect of circumnavigating Africa a reality. News of Columbus’s discoveries did not reorient their desire to find an eastern route to Asia. Pedro Álvares Cabral, who commanded the first Portuguese fleet to set sail after da Gama returned to Lisbon in 1499, only touched down briefly in Brazil because his primary objective was India. Once the Portuguese mastered the Indian Ocean, they continued to expand their base of operations in this region with varying degrees of success. In 1514, King Manuel I magnanimously sent an Indian elephant from Lisbon as a tangible demonstration to the pope of just how far Portuguese empire extended. The Rhinoceros that followed a year later died in a shipwreck in 1516 before reaching Rome but lived on in artist Albrecht Dürer’s famous image of an exotic animal he had never seen but drew from a description.

Despite the great publicity proclaiming the discovery of a “New World” in the Americas, many early modern Europeans continued to see Africa, the Middle East, and Asia as more important to their vision of the world. Between 1480 and 1609, Europeans published about four times as many books on the Ottoman Empire and Asia as they did on the New World. Varthema’s Itinerary was among them. Well into the 17th century, the French and the English continued to dream of a Northwest Passage. Samuel Champlain hoped that further exploration of the St. Lawrence River would lead him from New France to China, while a 1634 French map indicated a potential passage to Japan via the Great Lakes. Geography was as much about desire as reality, especially when dealing with the unknown.

During the 16th century, the number of Europeans traveling east increased dramatically. Varthema is a precocious example of a European eager to see Asia. The Portuguese ennobled Varthema for his service as a factor, the agent in charge of a commercial trading outpost. He belonged to the first generation of Europeans who no longer assumed that the primary conduit to the East was a Venetian ship headed to Cairo, Alexandria, Aleppo, or Constantinople. At the beginning of the 16th century, the Genoese had largely departed from the Eastern Mediterranean. The Venetians navigating these waters engaged in a delicate ballet with the Ottomans whose piratical incursions threatened many Italian coastal towns as their empire expanded further west. Portuguese caravels became the primary transportation for successive generations of Europeans to develop a far greater knowledge of and presence in the East, transforming it and themselves in the process.

As Varthema made his way back to Italy, a Portuguese adventurer named Duarte Barbosa (1480–1521) decided to write a careful account of his travels along a similar route. Tellingly, he began his journal as he rounded Cape of Good Hope since he understood that the Guinea Coast was already familiar territory after a half-century of military and economic incursions by the Portuguese in Africa. Instead, the eastern coast of Africa – and fundamentally everything between there and Marco Polo’s legendary Cathay – remained largely unknown. Barbosa carefully described a region of the world undergoing great transformations.

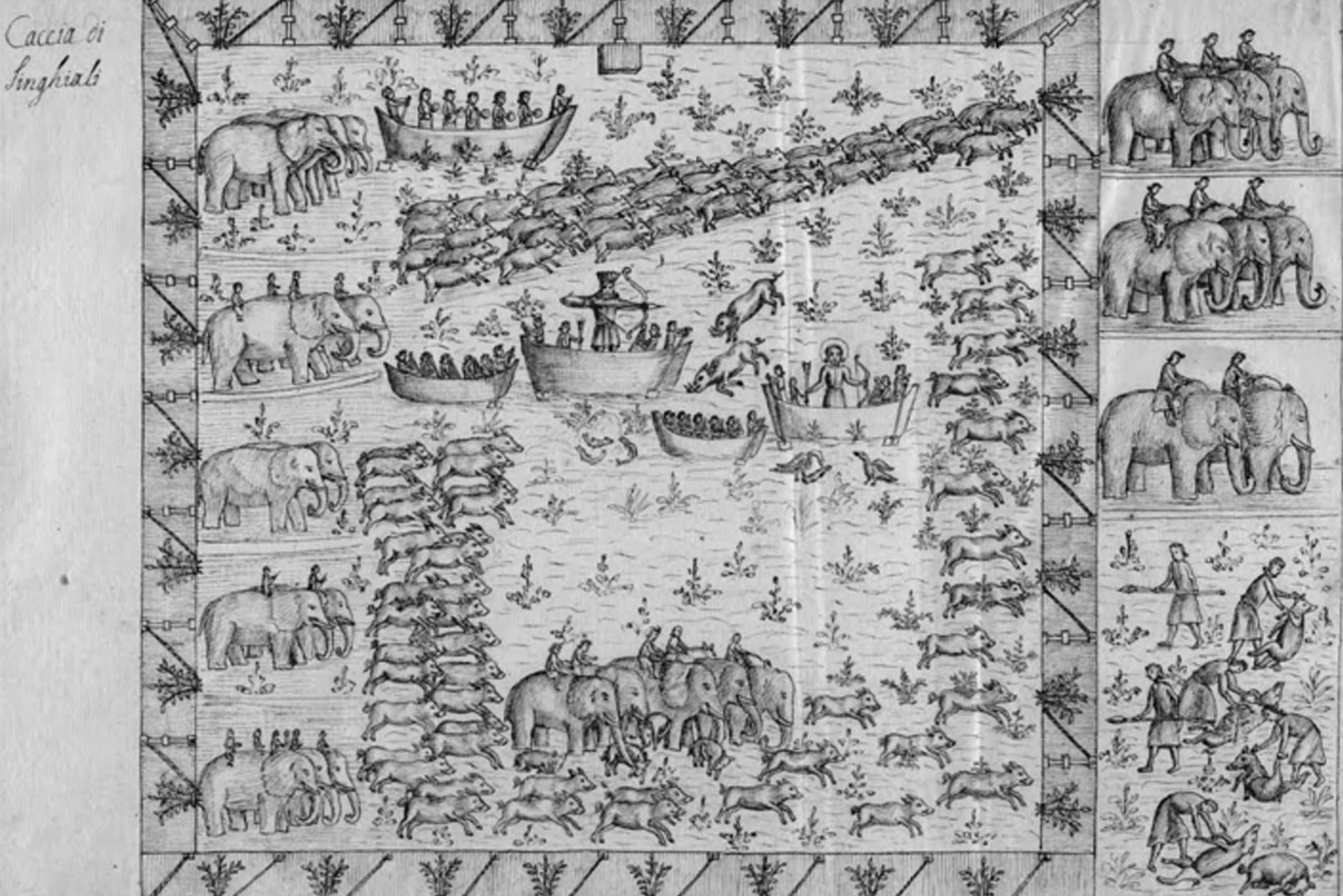

As his ship left Mozambique behind, island hopping until it reached the mouth of the Red Sea, he reflected on how the Portuguese left a wake of devastation and destruction behind them. Barbosa described well the Portuguese technique of fortifying strategic locations to establish a permanent presence, discouraging competition and resistance by military force, and making strategic alliances with local rulers eager to do business with the Europeans at the expense of the Muslim merchants and rulers who preceded them. By the time he reached the island of Hormuz, initially conquered by the Portuguese in 1507 to control trade routes through the Persian Gulf, Barbosa had established the pattern by which the Portuguese advanced from East Africa to the Indian Ocean.

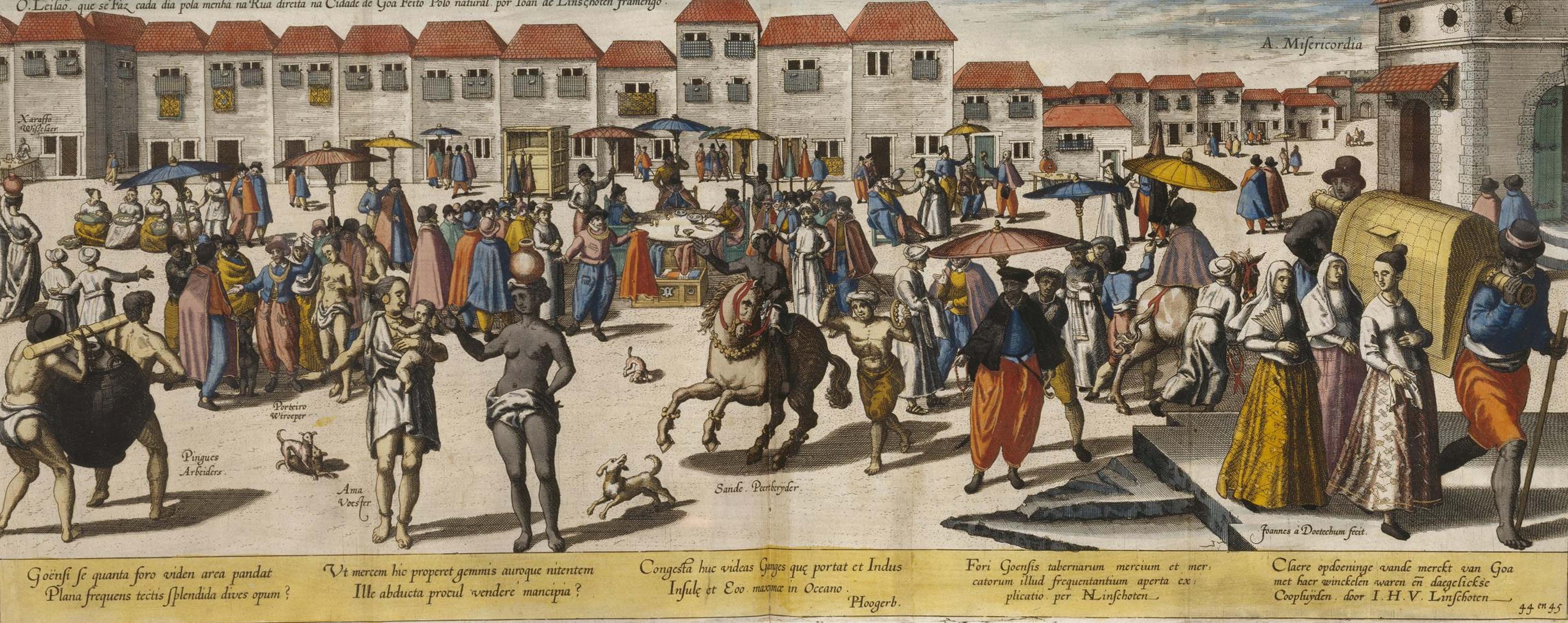

Barbosa served as factor in Cochin and Cannanore and learned Malabari. His described Goa as a polyglot colonial city in the making, filled with “Portuguese, Moors, and Gentiles.” Fascinated by the Brahmins as well as the “Christians of India,” he looked for traces of European merchants and missionaries who had preceded him. At the Cape of Cormory he noticed an Armenian church, containing tombs with Latin inscriptions, now become a place of worship for passing sailors. The cosmopolitanism of the world he found enthralled him; only one remote island struck Barbosa as so uncivilized that it brought to mind “the people of the Canary Islands.” He mistook African yams for American maize, yet ultimately, it was Asia that most interested him. Barbosa’s Book of What I Saw and Heard in the Orient circulated for approximately 40 years in manuscript form among the Portuguese, Genoese, and Spanish.

The Venetian editor Giovan Battista Ramusio finally printed a version in 1554, encouraging the next generation of readers to believe what Barbosa said but certainly had not observed of the Chinese – that they were tall, beardless small-eyed men who dressed and spoke like Germans. Of the Formosans (Taiwanese), he had even less to say because “they have not come to India since the King of Portugal possesses it.” Such was the unreliable but not easily contested nature of global information in an age of contingent, long-distance encounters.

Captivity and Conversion

- Northwest Passage

- Samuel Champlain

- Interest in and novelty of the New World, Amerigo Verspucci

- Accuracy of global information

- Giovan Battista Ramusio

- Leo the African

- Johannes Leo de Medici

- Al-Hasan al-Wassan

- Round Africa to India

- Fernao Mendes Pinto

- St. Francis Xavier and Jesuit missions

- The Great Wall

Section Focus Question:

What were the experiences of al-Wassan and Fernão Mendes Pinto?

Key Terms:

Ramusio published some of the most informative accounts of the regions of the world that greatly mattered to European ambitions in his Navigations and Voyages (1550–59), with each volume focusing on travel accounts of different parts of the non-European world. Tellingly, he began with Asia and Africa before collecting some of the most interesting reports of the Americas. In 1550, he printed a Description of Africa written around 1526 by al-Hasan al-Wazzan (ca 1492–ca 1550). Raised in Fez, he was the learned agent of the sultan of Fez, Muhammad II, and born in the final days of Muslim Granada before its reconquest by the Spanish. In 1518, he was captured by a Spanish pirate while returning from Arabia after he had witnessed the Ottoman conquest of Egypt. Al-Wazzan spent nine years in Italy where he converted to Christianity in 1520. The Medici pope, Leo X (who received the gift of Hanno the elephant,) baptized him with the Christian name of Joannes Leo de Medici, though he would call himself “Leo the African.”

While improving a prior Latin translation of the Qur’an and writing about Africa, al-Wazzan heard the Portuguese describe their discovery of the kingdom of the legendary Christian ruler Prester John in Ethiopia. Before returning to North Africa and renouncing Christianity, al-Wazzan witnessed the 1527 sack of Rome by imperial troops; he probably experienced Charles V’s conquest of Tunis in 1535, perhaps involving some of the same soldiers. Although al-Wazzan never managed to write about his experience of Europe and parts of Asia, his Description of Africa remained the most important and comprehensive account of Africa read by Europeans for the next two centuries, written by a European-born Muslim who, for a period of his life, was a Christian serving the pope.

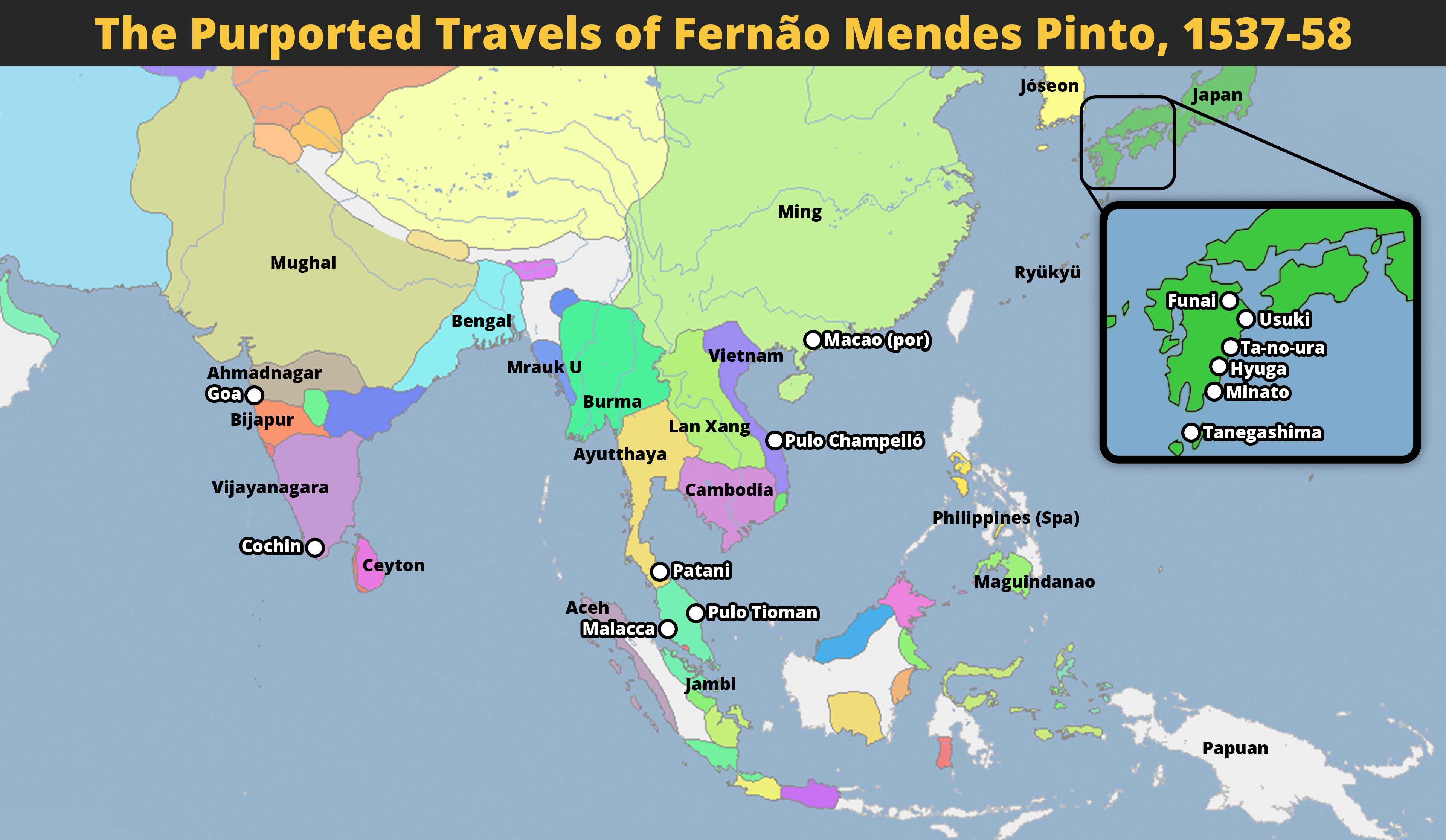

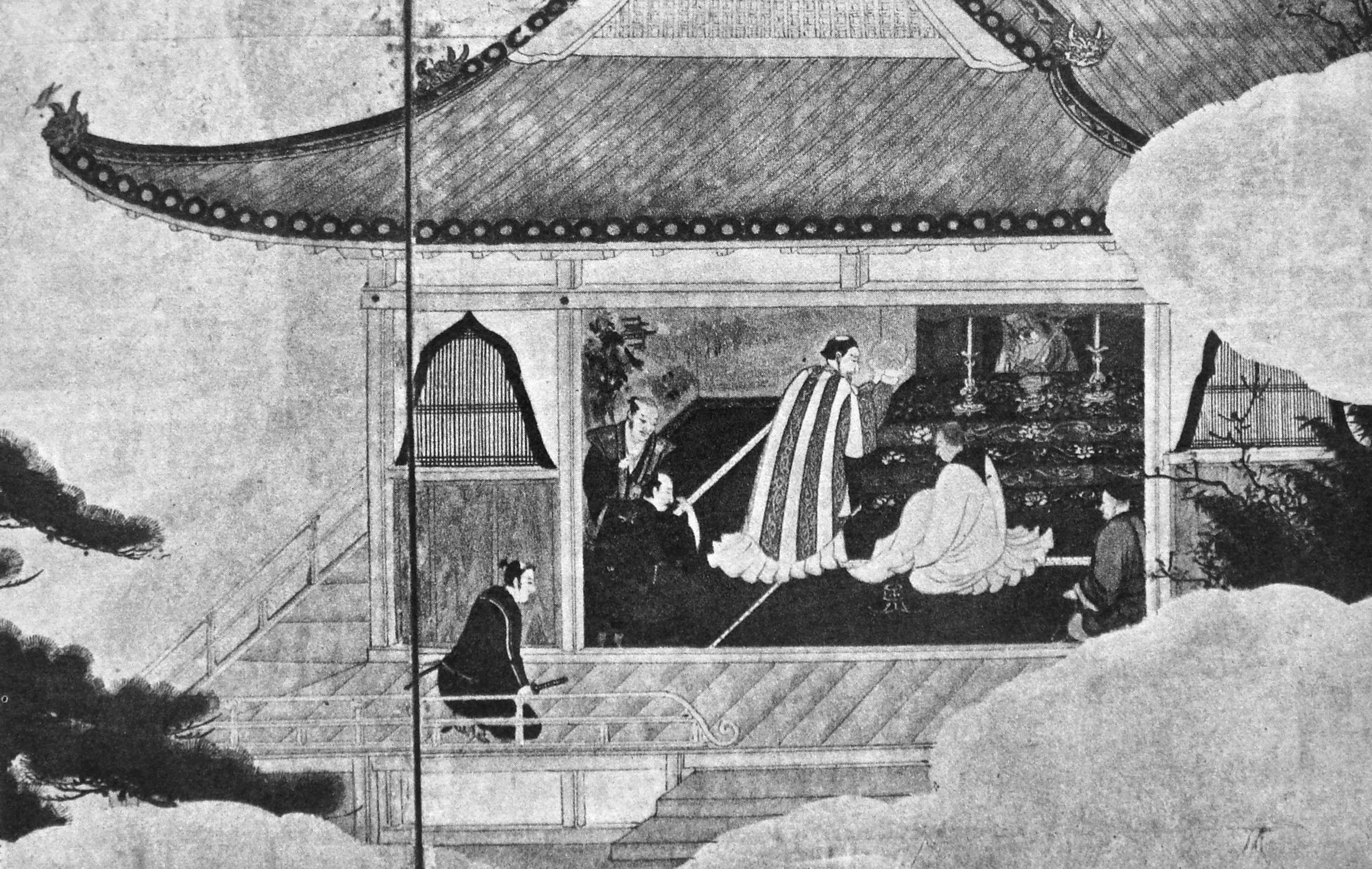

By the mid-16th century, entrepreneurial Europeans ventured beyond the edges of empire. Take the case of the notoriously unreliable Fernão Mendes Pinto (ca 1510–83) who spent two decades in Asia after leaving from Lisbon in 1537. Whether he ever touched ground in Ethiopia or went beyond Canton in his alleged excursions to China is uncertain. His four voyages to Japan did indeed take place – he proudly claimed to be the first European to set foot in Japan when his ship was blown off course to the island of Tanegashima around 1543.

By the time Mendes Pinto’s Travels appeared in print in 1614, he seemed the very embodiment of the kind of opportunistic European whose chameleon-like identity allowed him to assume many guises. Was he captured and enslaved by the Ottomans somewhere between Eastern Africa and the Red Sea? Did he become a pirate between the Gulf of Tongking and the South China Sea who allegedly (and rather improbably) served a year of hard labor working on the Great Wall? Did he fight against the Portuguese viceroy in Burma yet represent him as a quasi-ambassador to the daimyo of Bungo on his final trip to Japan?

His admiration for St. Francis Xavier (1506–52), who pioneered the Jesuit mission to Japan, was quite sincere. Xavier inspired him to support Jesuit efforts to convert the Japanese to Christianity, including funding to build the first Christian church, but whether Mendes Pinto actually entered the Society of Jesus in Goa in 1554 for two years is open to doubt. Amerigo Vespucci, the smooth-talking Florentine who transformed his real and imagined voyages to the Americas into a bestselling book that earned him a continent, was not the only early modern traveler to tell a tall tale – or be celebrated and mythologized by others simply for having gone the distance.

Writing to the East

- Queen Elizabeth I's outreach to Russia and Persia

- Moroccan embassy to Queen Elizabeth

- Forces against Spain

- Mughal emperor Akbar

- William Harborne

- The Northwest Passage

- George Weymouth

- Queen Elizabeth I's letters

- Susenyos

- Jesuits

- Ambrosio Bembo

Section Focus Question:

What do journals and letter-writing reveal about the changing world to Europeans?

Key Terms:

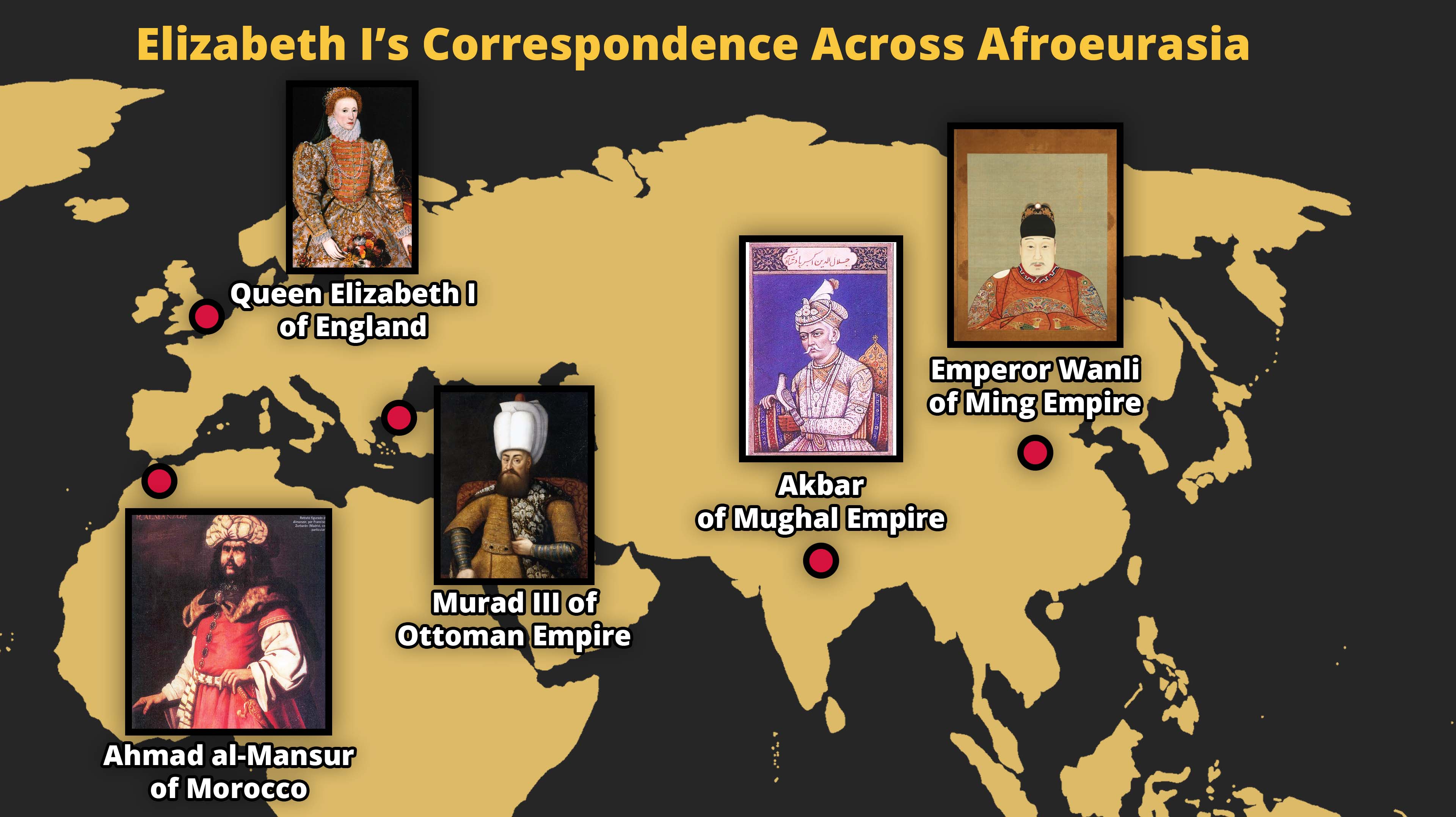

In 1561, Queen Elizabeth I wrote the first of multiple letters to rulers in the East, requesting that the Russian tsar and Persian shah offer her emissary, Anthony Jenkins, safe-conduct as he sought to gain trading privileges for the English. The shah knew a few things about the Spanish and the Portuguese but nothing of the English. Instead, in the 1570s the Moroccan and Ottoman sultans both wrote the English queen, seeking an alliance. The Moroccan sultan Ahmad al-Mansur’s efforts to court “sultana Isabel” was far more serious, as an independent North African nation vulnerable to both European and Ottoman ambitions. In 1589 a Moroccan embassy to London charged with encouraging the English to join a campaign to take Portugal from the Spanish floundered. A second embassy in 1600, the year al-Wazzan’s Description of Africa appeared in English, yielded no further commitments on the part of the English.

In 1583, William Harborne traveled through Persia with more royal letters, now addressed to the Mughal emperor Akbar and an unnamed “King of China.” However, Elizabeth I did not count on only one route for her message to reach her counterparts in Asia. In 1602 she wrote a new letter to the “great, mighty, and invincible Emperor of Cathay.” It was a description possibly inspired by the recent English translation of Marco Polo and reports about Matteo Ricci (1552–1610), invited to Beijing by the Wanli emperor in 1601 after years of working to develop the Jesuit mission in China.

The newly formed East India Company entrusted the queen’s second letter to George Weymouth (1585–1612), a captain employed to seek out the Northwest Passage. The letter was written in English but translated into Latin, Spanish, and Italian in the hope that a Jesuit such as Ricci might translate the contents for the emperor. It made it almost to Hudson’s Bay before Weymouth prudently decided he should go no further. Finally, in 1984, a British archivist delivered a copy of the letter to China. Hoping that this voyage would succeed where earlier ones failed, Elizabeth I warmly predicted, “By this means our countries can exchange commodities for our mutual benefit and as a result, friendship may grow.” It took another century for this desire to become a reality.

In the next decades two Ethiopian monarchs, Za Dengel (r. 1603–04) and Susenyos (r. 1606–32), wrote letters to the pope and King Philip III of Spain declaring their decision to embrace Roman Catholicism in lieu of Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity and asking for military support against their enemies. Paul V responded with the promise to send Amharic and Ge’ez type to print the Catholic version of the word of God in Ethiopia. In 1613, Susenyos attempted to send an embassy with the Jesuits to Madrid and Rome. It failed because of internal hostility from Ethiopian Christians and external pressures from the Ottoman Empire. Undeterred, he converted to Roman Catholicism and declared it the religion of his empire in 1624. This led to a succession of revolts that ultimately brought him to rescind this decision in 1632 while retaining his own religious conviction. His successors expelled and persecuted the Jesuits, and with them the Portuguese who traded in this region. By 1640 they neither wrote nor received letters from Catholic popes and kings.

In the 1670s, a young Venetian named Ambrosio Bembo (1652–1705) traveled through the Levant and India to see how much this part of the world had changed. He observed the decline of Portuguese Empire and thwarted Spanish ambitions in light of the growing presence of the Dutch, French, and the English. Each merchant flew the flag of his country on the top of his palace in Surat, and a seemingly infinite array of goods flowed in and out of the port cities. In Mumbai he ate an Anglo-Italian meal on Chinese porcelain with the half-Venetian Enrico Gay and his Indian Christian wife; he drank wine from the Canary Islands with the head of the English East India Company. While Bembo found “European things” costly in India, he was nonetheless able to purchase an elegant French suit. The world that Elizabeth I and her contemporaries hoped to encounter was now within their grasp.

Bembo marveled at the speed and variety of European news he was able to receive in Persia and India. It came from many different sources – Catholic missionaries, Protestant merchants and soldiers, and a wide variety of people making a living in this interconnected world who were in regular communication despite the distance. He jokingly observed that wherever he went, people asked if he was a physician. He did not mention meeting another Venetian, Nicolò Manuzzi (1638- ca 1720), who lived most of his life between Madras and Pondicherry and seems to have been a self-taught surgeon. Certainly, Manuzzi was an excellent example of why Italians were considered healers, and not only by resident Europeans.

Manuzzi is best remembered today for his History of the Mughal, a manuscript he sent to Venice in the early 18th century written in an eclectic mixture of Italian, French, and Portuguese. Manuzzi explicitly addressed his history to “the Europeans” – a category that became more meaningful to him after many decades in the melting pot of late 17th-century India where he could not see himself as exclusively Venetian. He was a European living in an East that was no longer mythical or vague because it had come into focus over the past two centuries. Sending and receiving letters, sharing news, living, intermarrying, and doing business in a complex world reshaped by European ambitions, he epitomized the European who wrote from the East and, unlike Marco Polo, chose not to return home.