Severe Mental Disorders: Schizophrenia and Bipolar, and Treatments

Note to students: The best preparation for taking the reading quiz is to pay close attention to the key terms as you read. Each question in the question banks is directly linked to these key terms and phrases.

Chapter Focus Question:

What are the natures of severe mental disorders and what is done to treat them?

- Suicide

- Major Depressive Disorder (MAD)

- Women vs. men diagnosis

- Deficit of monoamine

- Antidepressant drug

- Effectiveness of antidepressant medication

- Prohibitions to antidepressants

- Advantage of CBT for depression

Section Focus Question:

What is Major Depressive Disorder (MAD), the causes and treatments?

Key Terms:

Major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder are two fundamental clinical problems that capture the extreme highs and lows capable of human mood. While major depressive disorder (MDD) is much more frequently diagnosed, both MDD and bipolar disorder carry the highest estimated suicide statistics of all clinical problems. While schizophrenia is unique among clinical disorders in that it represents a break from the experience of reality, it also has a relatively high suicide rate. All three can cause considerable distress and impairment in functioning. This chapter will consider major depressive disorder and two forms of abnormal behavior often called severe mental illness — bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.

Diagnosing and Treating Major Depressive Disorder

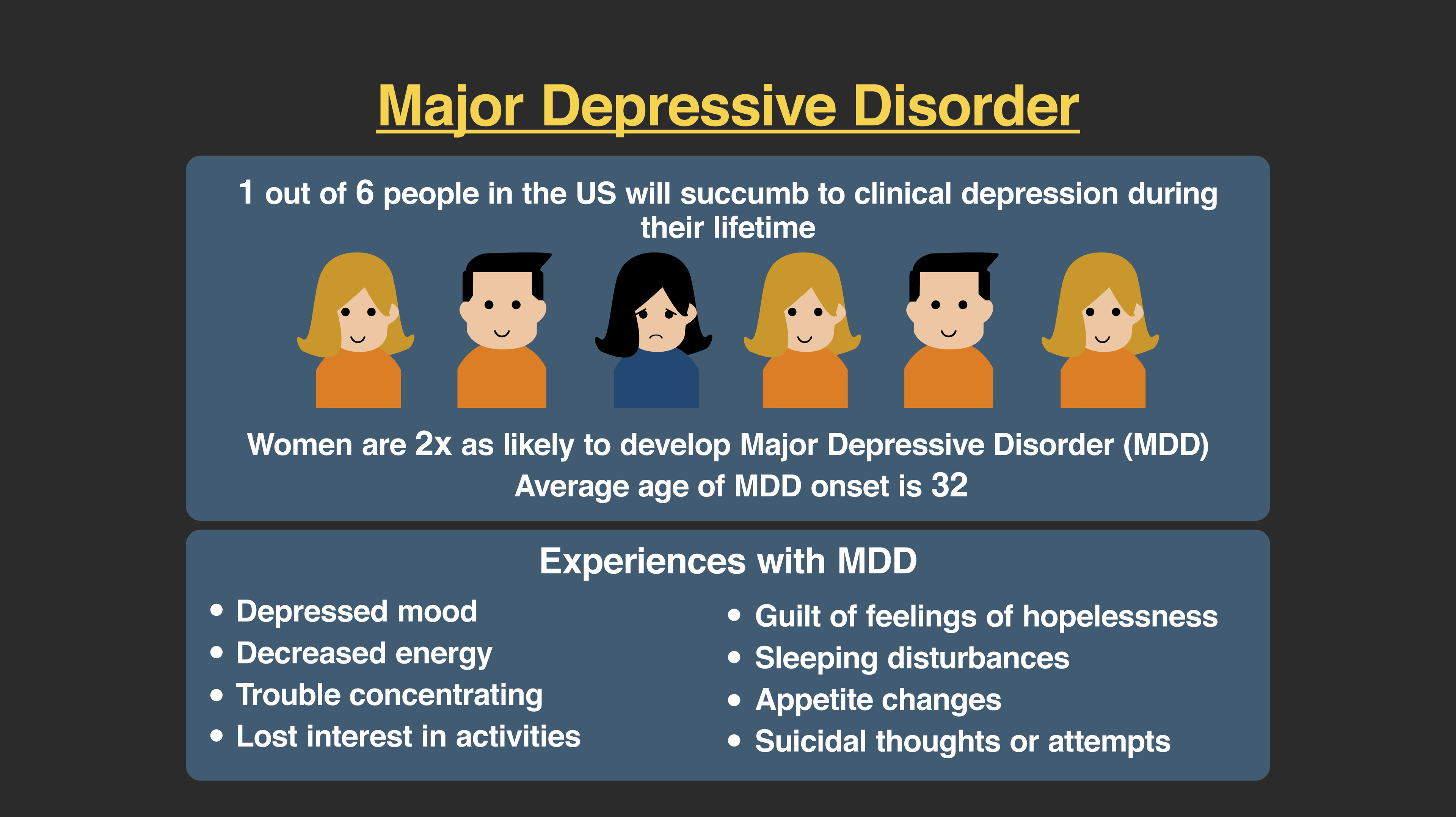

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM ) as a two week or longer period of depressed mood with symptoms including changes in appetite and weight, changes in sleep (including insomnia), loss of interest or pleasure (called anhedonia), fatigue, slowed or agitated behavior, excessive feelings of guilt, and recurrent thoughts of death. MDD has been documented to have a prevalence rate in America between 12 and 20 percent in one’s lifetime. This statistic is especially high given how profound the experience of depressed mood can be. Women are diagnosed with depression at a rate of two to one compared to men. Likely this is due to women being more willing to report psychological distress, while men are statistically more likely to engage in escape and avoidance behaviors related to alcohol or drug abuse. Still, there may be other important gender variables to consider that cause a higher prevalence rate among women including the experience of oppression or sexism.

MDD is the experience of profound sad mood, more than an experience of transient dysphoria or “the blues.” It is historically distinguished from grief (called bereavement in a clinical context) in that grief is a natural response to the loss of someone or something that is very important to us. Grief most often resolves naturally over time. Depression is not always as clearly tied to a specific event the way grief is. Some individuals who function well can become more and more depressed over time. This can be caused by a variety of stressors including work, relationships, or school, but sometimes it is hard to know what brings the feelings for some sufferers. To be diagnosed with MDD, it must cause a significant level of impairment in social role functioning or a subjecting sense of distress.

Research studies on depression show that many people diagnosed with MDD will often resolve on its own within one year. It is important to note that science also informs us that if an individual experiences a first episode of depression and is not treated, he or she will be more likely to relapse into another episode of depression later. This is an even larger concern given the higher rates of suicide that are associated with MDD. Although exact statistics are difficult to determine, the rates for completed suicide with those diagnosed with MDD are estimated to be as high as 15 to 17 percent. Some studies estimate that as high as two-thirds of all suicides are completed by individuals with (often untreated) depression.

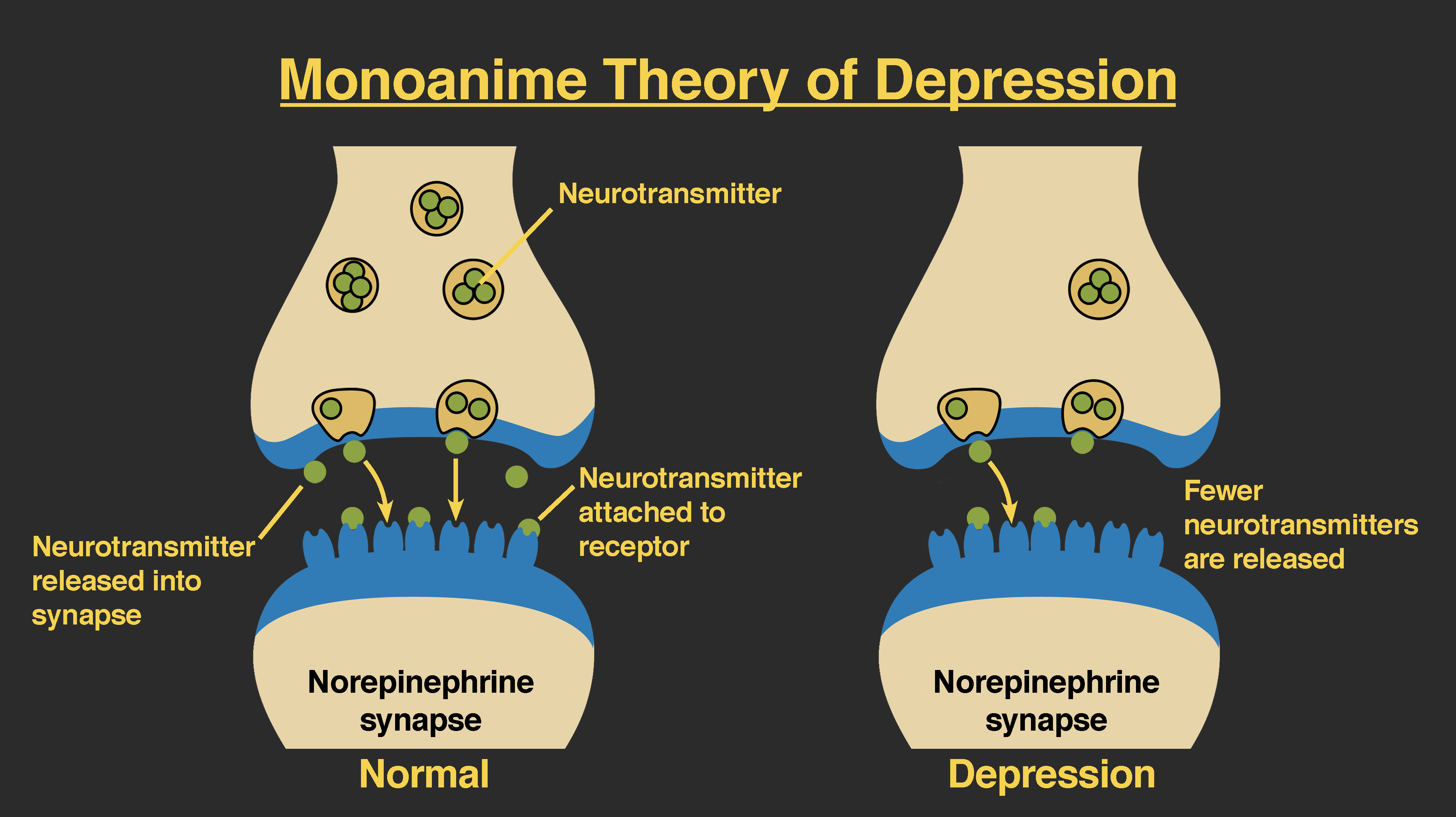

There are two dominant contemporary views on the cause and treatment of an MDD, biological understanding and cognitive-behavioral approaches. From a biological model, depression is caused by low amounts of certain neurotransmitters, chemicals in the brain that facilitates communication between important structures called neurons. The specific neurotransmitters are often identified as serotonin and norepinephrine and are in a group called monoamines (that also includes dopamine). The biological hypothesis suggests that there is a deficit of monoamine activity occurring in critical parts of the brain. This is an important hypothesis as the drug treatments for depression stem directly from this model.

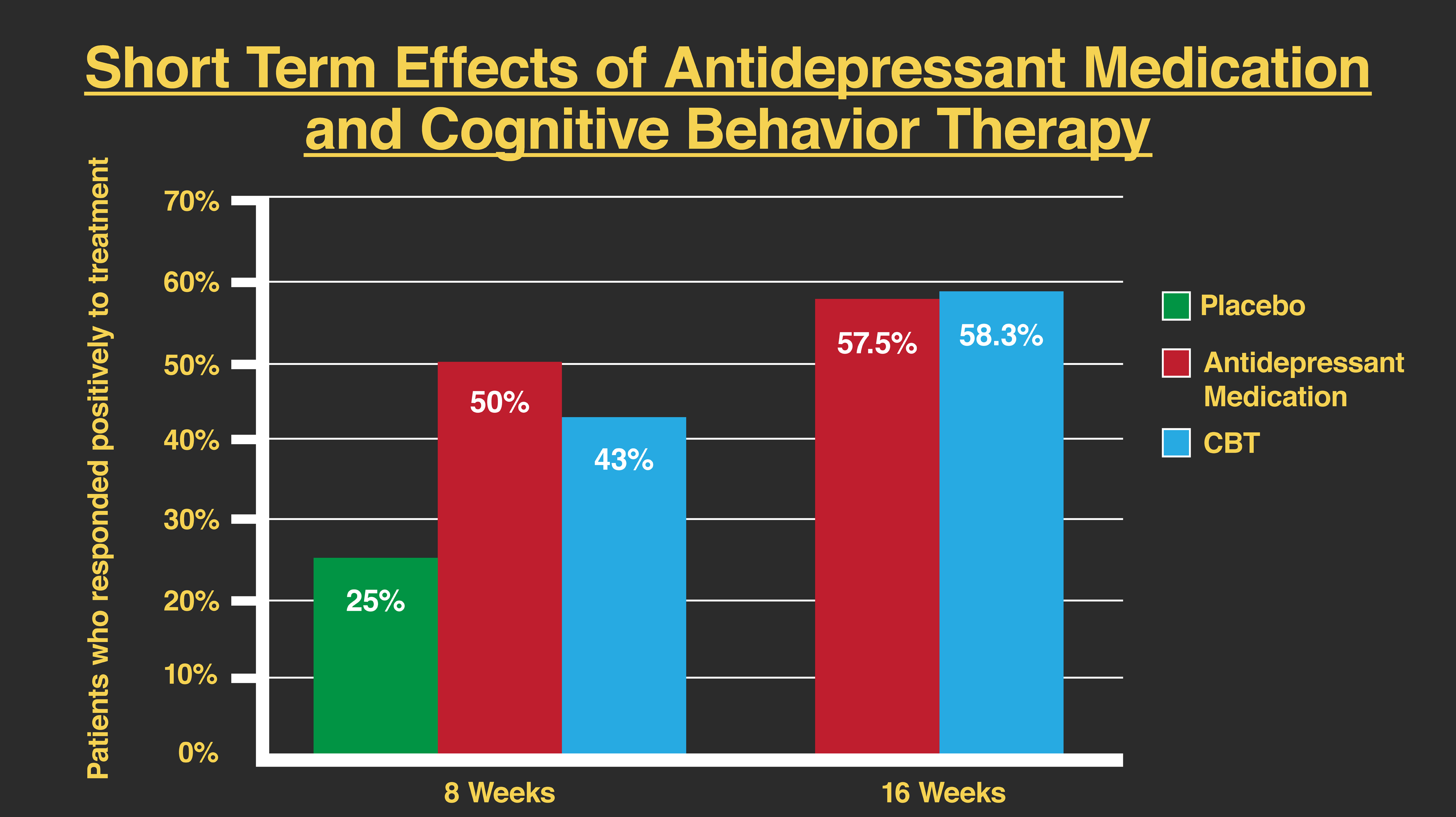

Antidepressant medications remain the most prevalent approach to the treatment of MDD. Drugs like MAOIs (monoamine oxidase inhibitors), tricyclic antidepressants, the SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), and atypical antidepressants (including dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors) all work to increase the levels of monoamines in the brain, assuming that this change will alleviate the depressed mood. However, the scientific data on the effectiveness of antidepressants is complex. On the one hand, we have many studies showing that antidepressants may help those with depression feel less depressed. On the other hand, there are data from other studies showing there is a large expectancy or placebo effect to these drugs. This placebo effect indicates that the improvements that we see with antidepressants may be more about the patient hoping he or she will feel better than the drug making that happening. In addition, there are recent studies showing that these drugs may not really have an impact on depression and that the effect that was shown in the past may have been exaggerated. That is especially important to consider given that there are many barriers to taking these prescription drugs including financial costs and the experience of side effects (including sexual dysfunction).

An alternative model to the biological perspective can be found in cognitive-behavioral theory. From a cognitive-behavioral model, depression is caused by the dysfunctional beliefs that we have about ourselves, others, and the future. In addition, it includes the behaviors that we have learned that get us into trouble (like escape and avoidance behaviors) and those skills we have not learned that would allow us to connect with others and engage in life more effectively. Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) for depression is consistent with those strategies outlined in the previous chapter for anxiety disorders. In this case, the CBT therapist collaborates with the client to identify dysfunctional core schema that contributes to the person’s sad mood. The client may have core beliefs that he or she will be alone forever, is helpless or powerless, or is defective in some way. A client who thinks this way may be more inclined to withdraw and not engage in life very effectively. The client may even push others away. It would be easy to imagine that the person’s mood would be quite depressed.

A CBT therapist working on cognition would challenge these dysfunctional core schemas and help replace them with more accurate beliefs. From a cognitive perspective, this would give rise to more effective client behaviors and improve the person’s mood. On the behavioral end, the CBT therapist would instruct the client in skills that would be more likely to create effective relationships with people and would increase the client’s activity level. This latter approach, part of an intervention called behavioral activation, has been shown to be very effective in reducing depression; for many people, exercise — simply taking a walk — can help improve mood. By going outside and engaging the world, not only does one's mood improve, but a person has increased chances of interacting with others, and social engagement appears to be important to a person’s positive mood.

There is excellent scientific evidence for the effectiveness of CBT. This therapy performs as well as antidepressants in clinical research, and the relapse rates for those in the CBT condition are much lower than for medications. The data from multiple studies show that up to 80 percent of those patients who take antidepressants relapse within one year of stopping the medication and almost 50 percent who stay on the medication relapse in the same time. These are much higher rates than for those who receive CBT where relapse rates are as low as 10 percent at one year. While neither treatment approach can help everyone with depression, CBT appears to be a much longer-lasting intervention for those diagnosed with MDD.

Bipolar Disorder and its Treatment

- Bipolar disorder description

- Bipolar disorder and suicide

- Reason for depression episode

- Mood stabilizing medications

- Lithium

- Side effects of drugs

- Desire for manic episodes

- Stress

Section Focus Question:

What is bipolar disorder, the causes and treatments?

Key Terms:

Bipolar disorder is characterized by a major depressive episode and mania, a mood experience at the other end of the continuum. A manic episode is characterized by an extremely elevated or elated mood (sometimes by irritability) and increased energy that lasts for at least one week. To be diagnosed with a manic episode, the person would also demonstrate a decreased need for sleep (only needing a few hours per night), a great deal of distractibility, increased desire for pleasurable activities that are risky, an experience of racing thoughts, talking very quickly, or an inflated sense of self-esteem. It is important to note that many of these behaviors or symptoms can accompany intoxication on stimulant drugs like cocaine or amphetamine, and to diagnose a manic episode, those causes for the mood change must be ruled out. A manic episode cannot be caused by drug use.

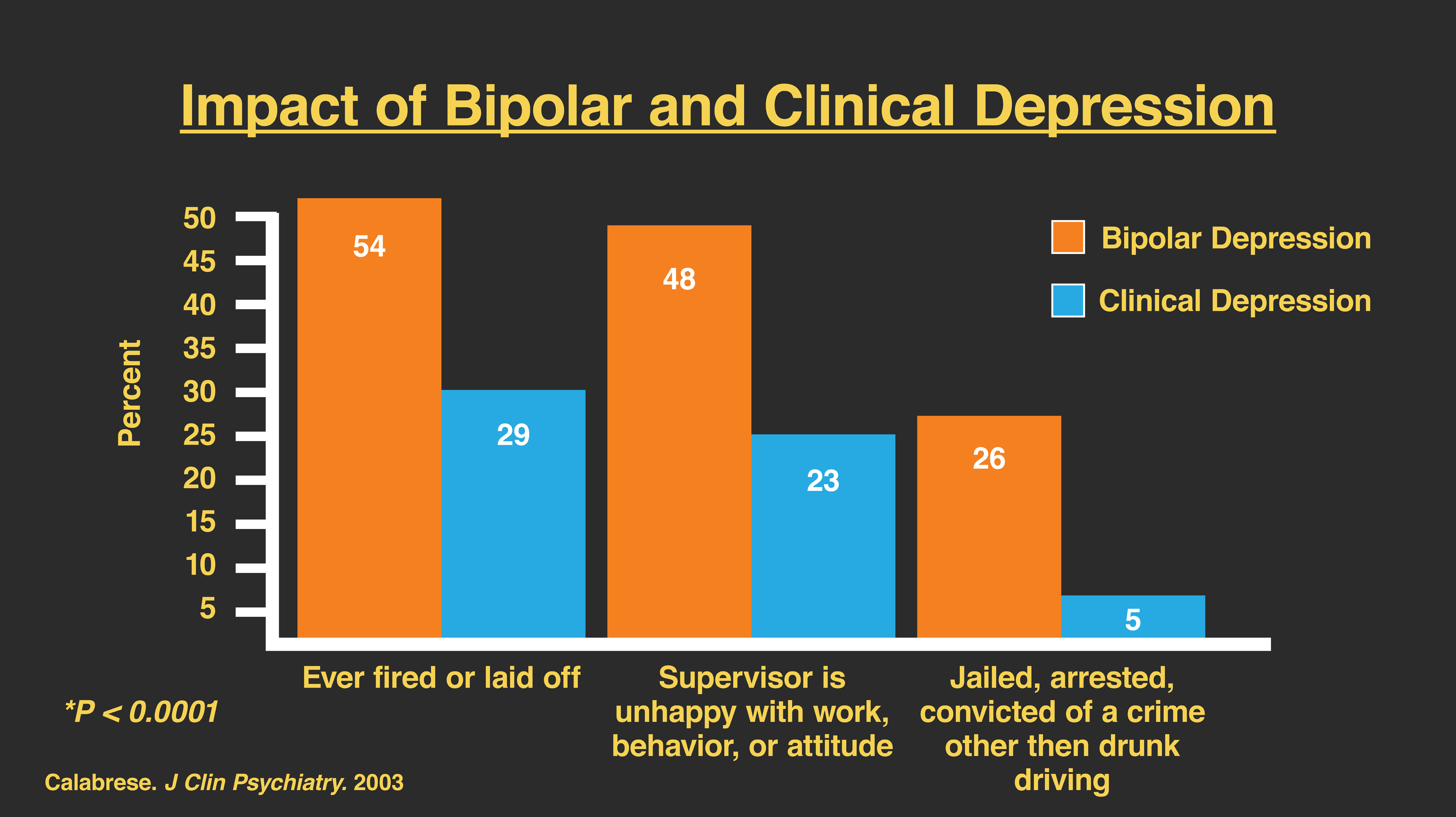

While it remains unclear precisely why a manic episode follows a major depressive episode, it seems reasonable to suspect that the brain and the rest of the body cannot physiologically sustain the experience of mania. The depressive episode is often experienced as profound sadness, in part because of the contrast with the mood that preceded it. As many as 20 percent of those diagnosed with bipolar disorder take their own lives, making it the disorder with the highest frequency of completed suicides. Still, it is not fully known what causes bipolar disorder. Most mental health professionals believe there is a strong (if not central) biological cause to bipolar disorder. From this assumption, the primary intervention for bipolar disorder is the use of what are called mood-stabilizing medications.

The most commonly prescribed and most effective drug treatment for bipolar disorder is lithium. Lithium is a simple salt that effectively reduces mania and future manic episodes for as many as 60 percent of patients. Lithium acts more as an antimanic than an antidepressant, and often patients are prescribed several medications to manage the disorder. Unfortunately, while effective for many, lithium is difficult to take and damages the kidneys, problems that gave rise to other drug treatments. Other medications used to treat bipolar disorder include those called anticonvulsants (originally developed for seizure disorders like epilepsy) and antipsychotics (discussed later in the section on schizophrenia). All of these medications can help improve the lives of those diagnosed with bipolar disorders, but they also have numerous side effects and can be very hard to tolerate, making compliance with treatment harder. In addition to the difficulties with side effects, patients diagnosed with bipolar often times will stop taking medications because they miss the experience of a manic episode and report that life feels “boring” without that experience.

CBT and other interventions bring psychological strategies to the medical management of bipolar disorder. These treatments provide psychoeducation to help the client learn more about the disorder, the importance of being compliant with medications, and when to present for treatment and support at the onset of either a depressed or manic episode. In addition, family-based interventions have been shown to be successful for bipolar disorder when the focus of the treatment is to help decrease stressful, critical, and hostile interactions between patients and loved ones. These treatments when combined with mood-stabilizing medications can effectively decrease relapse and hospitalization rates.

The Diagnosis and Treatment of Schizophrenia

- Prevalence of schizophrenia

- Psychosis

- Delusion

- Hallucinogenic

- Delusional experience

- Onset of schizophrenia

- Excessive dopamine

- Schizophrenia and violence

Section Focus Question:

What is schizophrenia, the causes and treatments?

Key Terms:

Even with the complexities and problems associated with bipolar disorder, one of the most profound diagnosable disorders remains schizophrenia. Schizophrenia is part of a group of diagnoses called psychotic disorders. Clinically, psychosis refers to a state where a person is no longer connected to or experiencing the reality shared by most people. Of all the clinical disorders, this is often the most difficult for people to understand because it is not part of most human experience. Unlike remembering or imagining feeling sad to help understand depression or the idea of being extremely nervous to understand some anxiety disorders, psychosis is unlike most people’s life experiences. In fact, schizophrenia, the most frequently diagnosed of the psychotic disorders, is very rare itself with an estimated prevalence rate in most countries of 1 percent(or less) of the population.

The experience of schizophrenia can include having delusions and hallucinations. Delusions are defined as false and fixed ideas that the person believes despite being presented with evidence to the contrary. Examples of delusions can include beliefs that the CIA or FBI is pursuing the person, that the person is a reincarnated god, or that he or she is receiving special signals from outer space. The challenge with determining if something is delusional lies with the criterion used to define psychopathology (as explained in the previous chapter on disorders and theories), that of the behavior lies outside an acceptable boundary set by the client’s cultural group. For example, if a client stated that he or she is a “child of God,” this might be completely normal in a specific religious culture and would likely not be considered delusional. However, in many cultures, if the client said he or she was the “child of God,” that would be considered delusional.

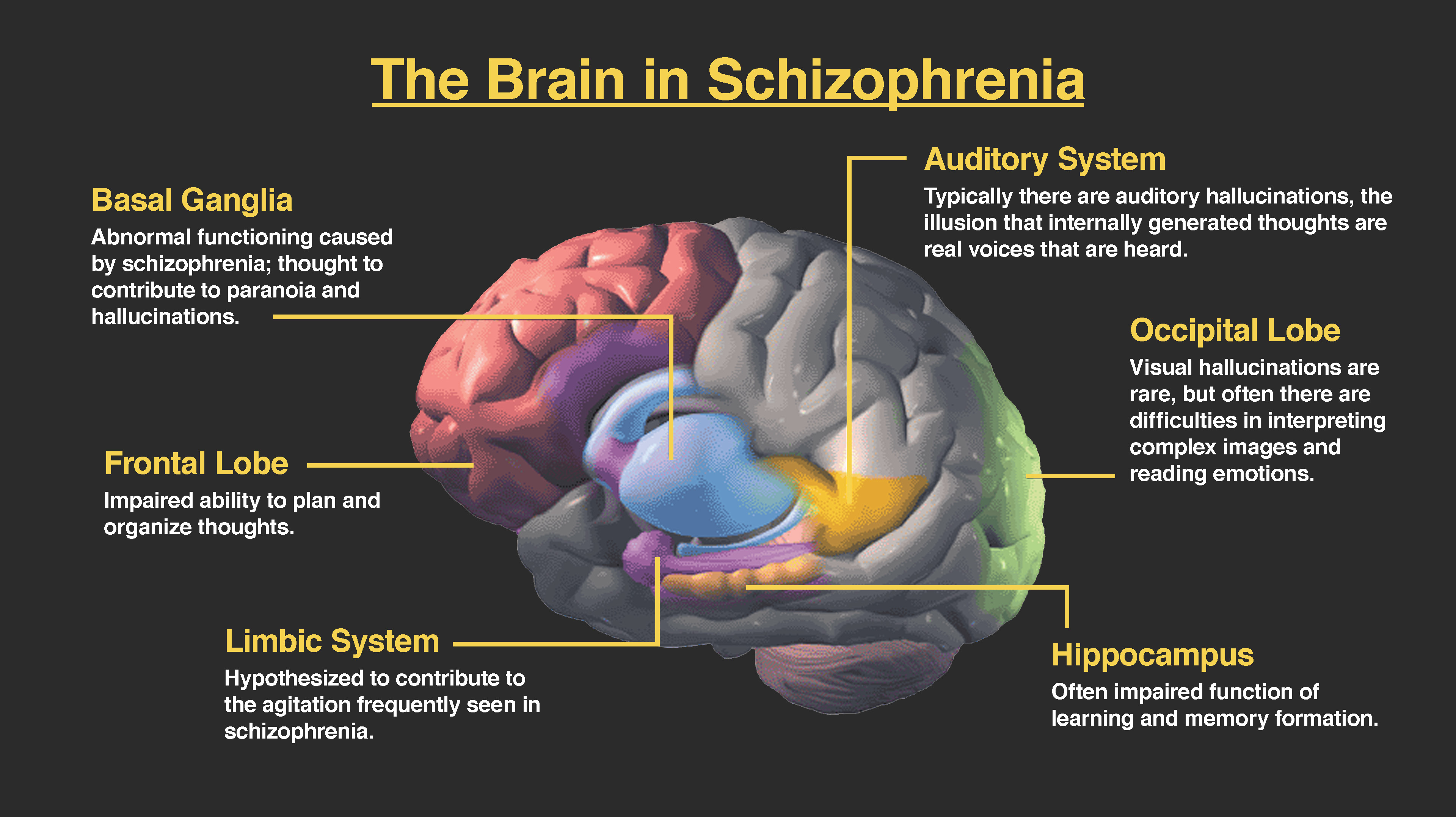

Hallucinations are defined as a perceptual experience in the absence of a real stimulus, for example, hearing a sound that does not actually exist. The most common type of hallucination observed in schizophrenia is auditory, hearing sounds that do not actually occur. These hallucinations can be of sounds like breaking glass or crying, and they can be specific voices talking to the person. Unlike when we talk to ourselves, auditory hallucinations are perceived as external to the person who experiences them. Despite the fact that movies often depict schizophrenic hallucinations as visual, these are much less common in this disorder and are more frequently caused by drugs or sometimes injury or damage to the brain.

Other problems observed with schizophrenia can include incoherent or disorganized speech where it is difficult to follow the content or meaning of what the person is talking about. The behavior of the person can also be considered disorganized, making its purpose hard to understand, or it can be catatonic. Catatonic behavior oftentimes refers to times when the person engages in a specific pose and does not move or displays repeated patterns of behavior that, again, appear without purpose. Finally, there is a group of problems called negative symptoms which characterize the absence of behavior we would expect to see. For example, we may see a lack of emotional expression, a decrease in caring or concern, or diminished goal-directed behavior. Diagnostically, schizophrenia lasts for at least one month and must include two of the problems outlined above.

Schizophrenia typically occurs for individuals in their late teens and early twenties. Men and women are diagnosed equally often, though males are more often diagnosed at a younger age than women. The course of this disorder can be quite varied. For some, the onset of psychosis is quite sudden, while for others it can come only much more slowly, even over several years, before a full episode is diagnosable. Moreover, not all individuals manifest schizophrenia for life. Research evidence suggests that a very small percentage of individuals has a single episode and never returns to normal functioning. Instead, most diagnosed with schizophrenia have multiple psychotic episodes throughout their life, but many can have periods of very high functioning.

As we saw with bipolar disorder, the cause of schizophrenia is not yet fully understood. There are several hypotheses, but the most commonly accepted is from a biological perspective. The hypothesis from this framework holds that schizophrenia is caused by an excessive amount of dopamine activity in the brain, particularly in structures related to higher order thinking and making associations (the frontal and parietal lobes). Some evidence to support this hypothesis comes from the finding that high doses of amphetamine (a drug that causes a great deal of dopamine to be released in the brain) can also cause some psychotic behaviors in people not diagnosed with schizophrenia. The dopamine model has some support, but many modern scientists believe that schizophrenia is a complex disorder that is likely caused by multiple factors and probably involves many neurotransmitter systems other than dopamine.

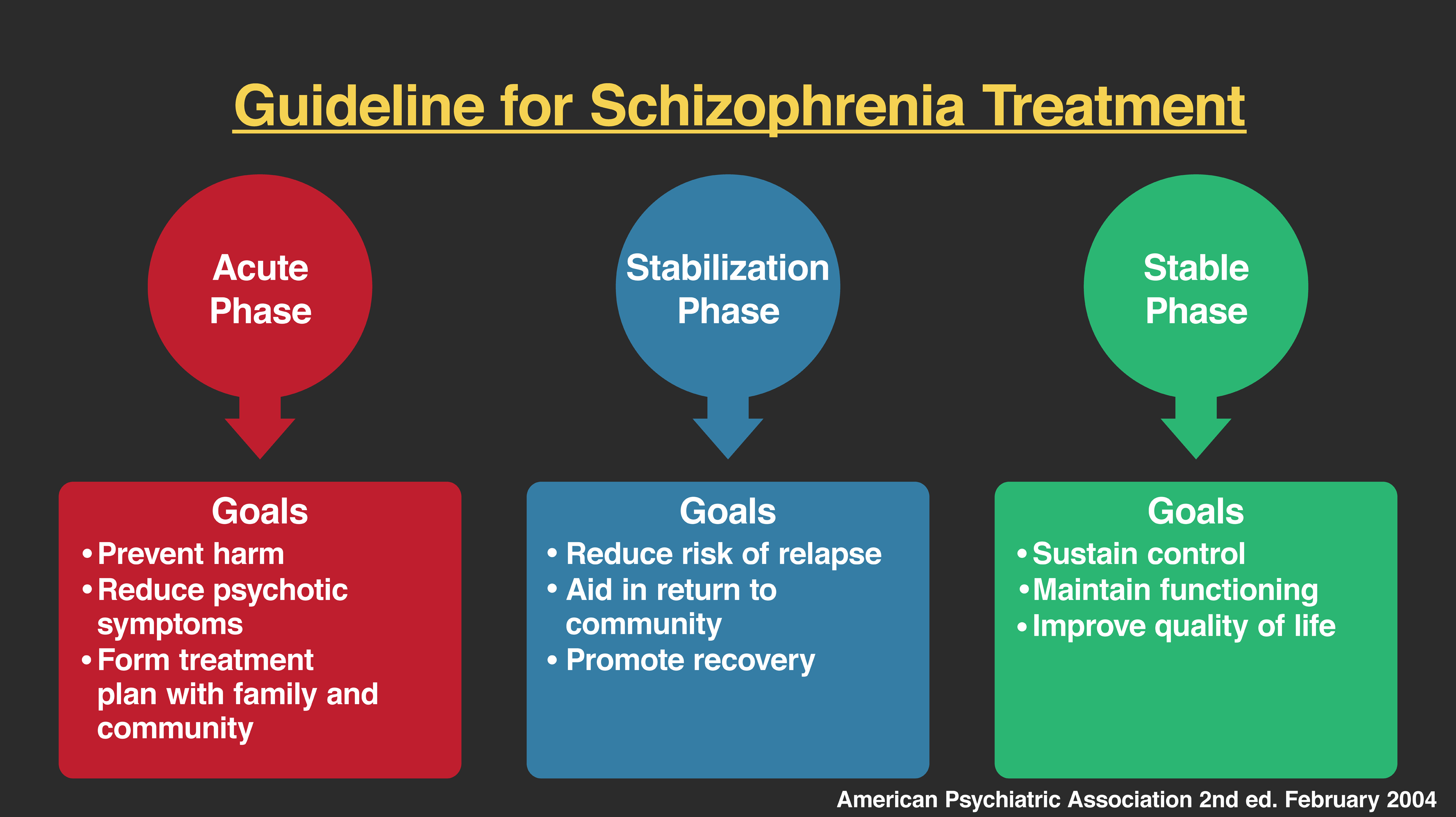

That said, the dominant intervention for schizophrenia is the use of antipsychotic medications that decrease dopamine activity, called dopamine blockers. Antipsychotics have been shown to decrease hallucinations and delusions in some patients. However, a percentage of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia do not respond to these drugs, and the drugs have major side effects. The difficulty with blocking dopamine in the brain is that some parts of the brain, including the motor cortex, rely heavily on dopamine and are easily damaged. This can produce one of the common side effects for antipsychotic medications, the appearance of physical problems like tremors and spasms that resemble Parkinson’s disease that can become permanent, in this case a set of symptoms called tardive dyskinesia.

Biological interventions can reduce psychotic symptoms and decrease relapse rates for patients by as much as 50 percent. This is considerable given how debilitating the problem can be for many people diagnosed with schizophrenia. The addition of psychological interventions such as those discussed with bipolar disorder can further decrease relapse rates. Psychoeducational interventions that focus on medication compliance, learning about the disorder, and the importance of seeking medical help when symptoms become worse are each helpful in reducing relapse and rehospitalization rates. In addition, family-based interventions that decrease factors like blaming, hostile interactions, and isolation in a family can be very helpful and further lower relapse rates similar to bipolar disorder.

It is worth noting that because schizophrenia is such a unique experience and so difficult for many to understand it has been misunderstood and misrepresented in the media. In fact, many films portray people diagnosed with schizophrenia as murderers and serial killers. While this depiction makes for exciting movies, it does not accurately represent the low rates of violent behavior seen with the disorder. There have been a few infamous people who committed murder who may have been psychotic, but the majority of homicides are committed by individuals who are not diagnosed with schizophrenia. In fact, research shows that on average, schizophrenic patients are less likely to commit violent crimes than those not diagnosed. Conversely, those diagnosed with a psychotic disorder are more likely to be the victim of a violent crime. This last statistic coincides with the fact that many of America’s homeless population suffer from severe mental illness including schizophrenia. This points not only to a need to better understand and treat this problem but also to the need to address the care and treatment of those psychological disorders at a societal level.