Disorders, Definitions, and Theories

Note to students: The best preparation for taking the reading quiz is to pay close attention to the key terms as you read. Each question in the question banks is directly linked to these key terms and phrases.

Chapter Focus Question:

How do we define and identify psychological disorders and what are the theoretical approaches we use to treat the disorders?

- Properties of abnormal psychology

- Statistical deviance

- Subjective sense of distress

- Impairment of social role functioning

- Indications of abnormal psychology

- Outside the bounds of cultural norms

- Overpathologizing

Section Focus Question:

What are the properties of abnormal psychology?

Key Terms:

Properties of Abnormal Behavior

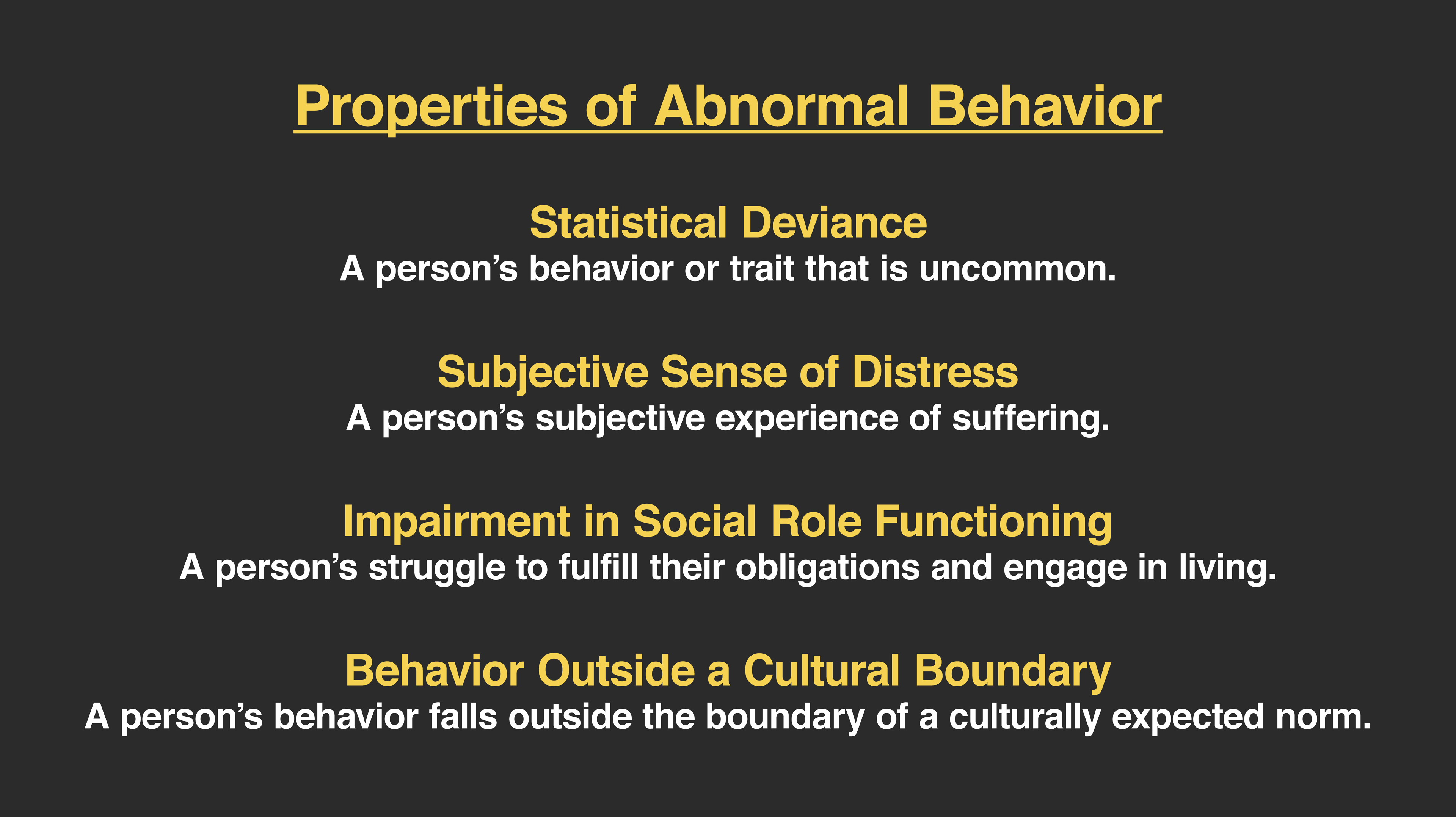

What qualifies behavior as abnormal or psychopathology? Interestingly, there are no specific and set qualities that equate to abnormal behavior. That is, there is no single agreed-upon definition of psychopathology and no single criterion that would determine that a psychological disorder is present. Instead, those who study and work with individuals having psychological disorders, mental health professionals (including clinical psychologists), focus on several properties of the behavior in question.

Statistical Deviance

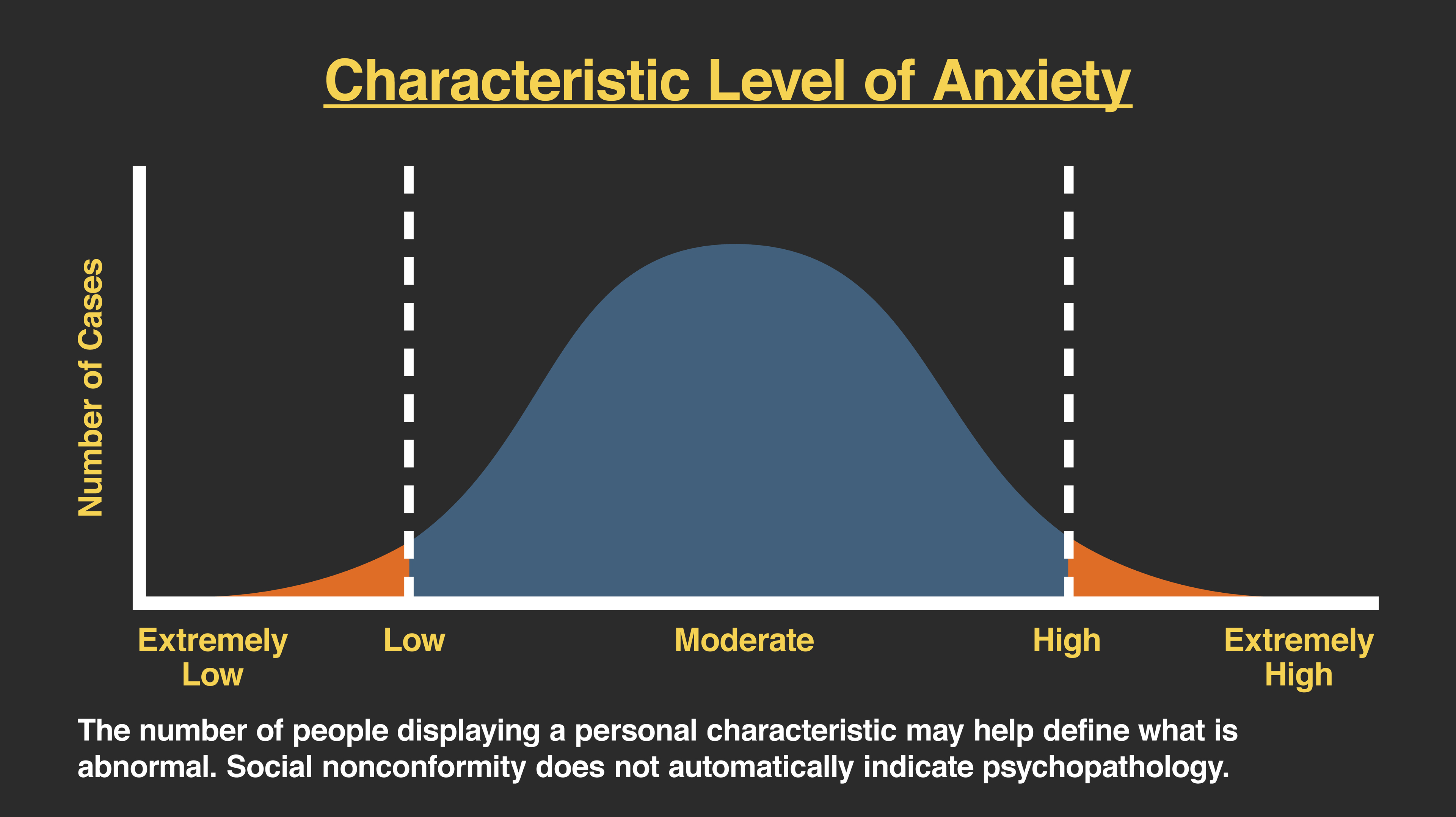

The first of these properties concerns the idea of statistical deviance. In this case, we can look to see how uncommon the behavior is or how much that behavior is different from an average observed in some group or population. If a problem behavior were infrequently observed in the culture, we could state that the behavior is abnormal because it is so statistically uncommon. For example, many people get angry, but very few, statistically speaking, commit murder. In this case, murder is statistically deviant. We can potentially use the same model to determine whether an amount of sadness a person experienced was statistically deviant. It is common for all of us to feel sad, but from this model, an excess amount of sadness may be what we view as depression (a disorder we will talk about in the next chapter).

Although the statistical deviance model has the appeal of being very objective and scientific, there are at least a few challenges to this way of defining behavior as psychopathological. First, to know whether a behavior is statistically deviant, we would need to know the average amount of that behavior in the population. From there, we could specify the extent to which the behavior deviated from that average. This would indicate just how rare that behavior actually is. The problem remains that we simply don’t know most of these averages. For example, what is the average amount of sadness we would expect in a population?

Another challenge with this model is that there is no clear definition for us whether the statistical deviation is abnormal and problematic in both directions from the mean. If there is too little of the trait, behavior, or emotion is that problematic? What if there is too much of that behavior? For example, if someone scores very low on an intelligence test, we would say that trait is abnormal because lower intelligence can have some real challenges in our culture (e.g., with intellectual disabilities). However, would we say that too much intelligence, which is equally uncommon but in the other direction, is also abnormal? In the case of intelligence, we do not say that a statistically high amount is deviant or problematic, and those individuals do not have problems in the culture. In fact, we often use the word genius to describe them.

Subjective Sense of Distress

Another property of abnormal behavior concerns the very personal or subjective experience of emotional distress by the individual. Many clinical psychologists will focus on this property when assessing a person who has psychological problems. Emotional distress is subjective, and different people will feel emotions like sadness, anger, anxiety, and loss differently. In fact, the degree to which one person feels sadness may be quite different from another person, even though both are really struggling with that experience.

The property of emotional distress helps mental health professionals determine whether behaviors are problematic or abnormal. For example, if a person feels anxious, in many situations that is normal. However, if that person feels anxious and he or she is extremely distressed by the thoughts they are having and in addition, the person experiences a racing heart and confusion, we might assess this level of distress as abnormal behavior. As another example, think about someone who is new to a group of people. It would be normal to feel some anxiety or trepidation in that situation. If the person instead felt so anxious that they couldn’t really stand to be around new people and their feelings were overwhelming, we would consider that level of anxiety to be causing subjective distress.

Still, as stated before, there is no single property that will work for all behavior to determine that it is abnormal. Even with the experience of a subjective sense of distress being so important in defining psychopathology, the reality is that this feature is not always present for those who are engaged in genuinely problematic behaviors or diagnosable disorders. Try to imagine someone who bragged so much about what they could do and was so arrogant that others simply never wanted to be around them. That person may get into conflict with people at home and work who didn’t agree with how much he thought of himself. You could probably guess that this kind of behavior, in its extreme, is considered to be abnormal or psychopathological, and you would be right. (It’s diagnosed as narcissistic personality disorder.) Still, you may also guess that the person who has such an inflated sense of self-worth does not actually experience a subjective sense of distress. In this example, the narcissistic person thinks he’s really great.

This sample challenge is also true for those whose mood is so elated or euphoric that they believe they can accomplish anything. When this is part of what we define as mania (part of bipolar disorder), the person does not feel a sense of emotional distress at all. Unfortunately, mania is a profound form of human suffering, and one that can have tragic consequences, even if that aspect of bipolar disorder is not always experienced with distress.

Impairment in Social Role Functioning

Another criterion we can examine to determine the presence of abnormal behavior or psychopathology is if there is an impairment in functioning. In this case, clinicians will look for dysfunction in any chosen social role for that person, be it as employee, homemaker, parent, student, teacher, nurse, member of the church, and so on. If the emotion or behavior we are noticing makes it so the person can no longer engage in their job, stay engaged at school, effectively parent, and so on, then that would be considered an impairment in social role functioning. This can be a useful criterion to use particularly when there is not a subjective sense of distress that is present. In our example of the especially arrogant person who was having job conflicts but was not distressed by his behavior, his work problems would meet this criterion for abnormal behavior.

As you may anticipate, this property of abnormal behavior also may not always be present. Consider someone who is sad enough to be diagnosed as clinically depressed. Even though that person may sometimes be overwhelmed by feeling sad, tired, or even hopeless, he or she may go to work and complete any obligations set by their social role. For this person, he or she may not have social role impairment, but we still see that the person shows a subjective sense of distress. Typically, mental health professionals look for and often find at least one of these two properties present when they are evaluating someone for a psychological disorder.

Behavior Outside a Cultural Boundary

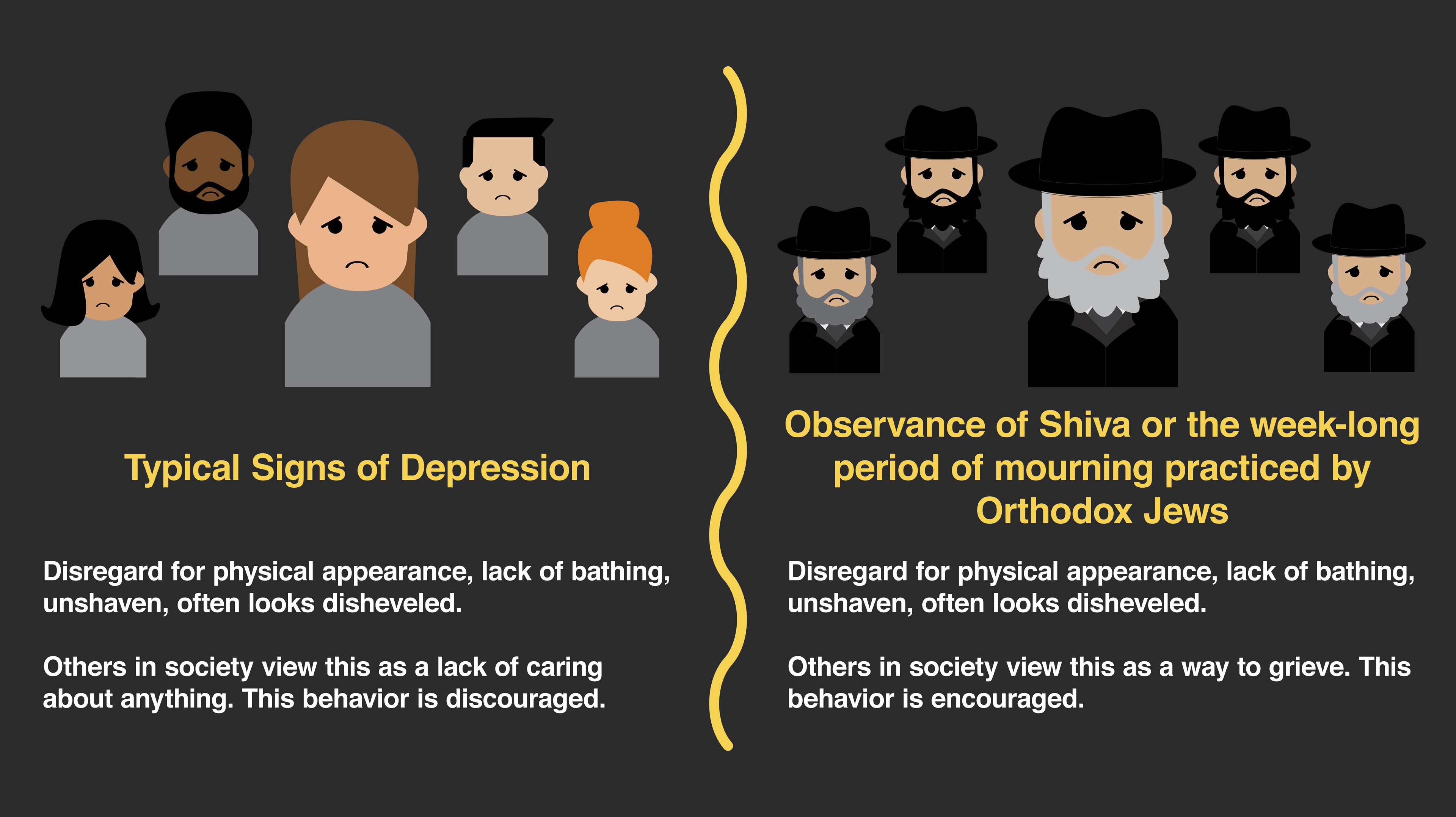

There is a final property of abnormal behavior to consider. It is very important but sometimes hard to fully appreciate. When a behavior falls outside the boundary of a culturally expected norm, it can help us understand whether the behavior is abnormal. As you can imagine, this is difficult to assess because there are so many different cultures. For someone evaluating a particular individual’s behavior as abnormal, he or she needs to appreciate what the expectations of that person’s culture are. The added difficulty here is deciding how one defines the term, culture. Is it the person’s ethnicity, is it the family culture in which the person was raised, is culture defined by the experience of gender or sexuality, and so on?

Although this is a complex property, considering cultural norms in evaluating behavior as normal or abnormal is essential. If a person expresses sadness that is viewed by a mental health professional as excessive, it is essential that we know the expectations for that person’s culture for expressing sadness. Are those expectations the same as the professional’s, in which case the behavior may be outside of the boundary set by the culture? Or is this expression of sadness consistent with how that emotion is experienced in that culture? In the latter case, when the reaction is how the person is expected to behave, we would want to be very careful not to label the behavior as psychopathological or abnormal.

When mental health professionals do not consider the cultural norms of the individuals they are evaluating, they can sometimes over-pathologize that person. It is not acceptable to label a behavior as abnormal simply because we perceive it differently from our own cultural experiences. Certainly, if the behavior possesses the properties we defined earlier — causing a subjective sense of distress and impairment in social role functioning — then we may find the behavior to be abnormal or meet the criteria for a psychological disorder. It is very important to remember that different is not necessarily deviant or pathological.

Classification of Psychological Disorders

- Assessment of abnormal psychology

- Drug effects

- DSM-5

- Disadvantages of DSM-5

- Source of the disorder

- Classifications of disorders in DSM

- Drapetomania

- Homosexuality

Section Focus Question:

What is the DSM and what are the problems associated with classifying psychological disorders?

Key Terms:

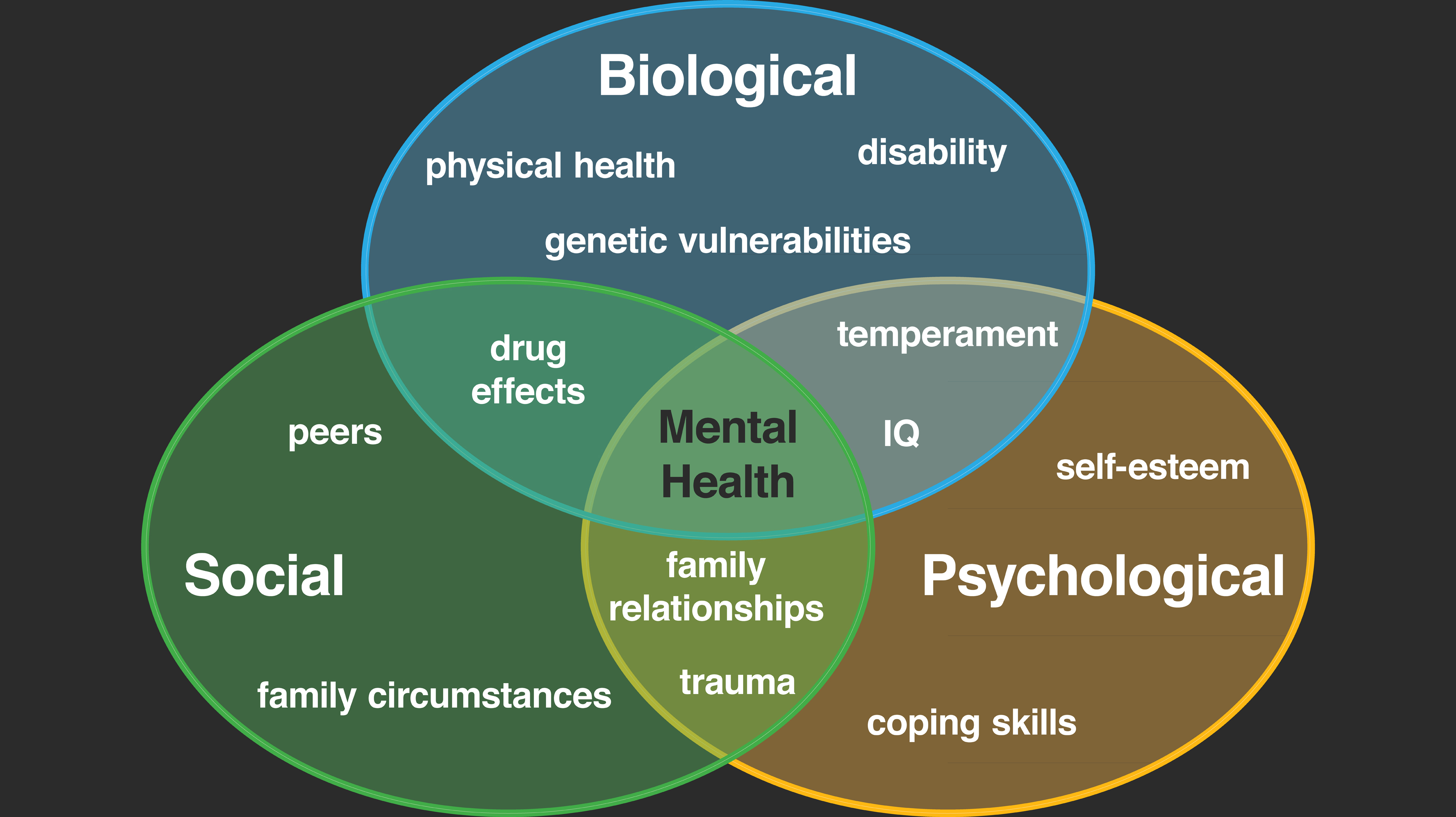

Assessment is the process of determining whether someone meets the criteria for abnormal behavior. Psychological assessments can be for a variety of issues. They can be for intellectual skills, emotional problems, difficulties with thinking, for personality traits, and many other issues. Here, we are focusing on psychopathology or abnormal behavior, so assessments are often used to focus on specific behavioral problems. Assessment is often a comprehensive evaluation of many aspects of an individual’s problems. A mental health professional may focus not only on abnormal behavior but on the context of the problem, including environmental factors or important relationships. The assessment may try to detail current and family histories that participate in the problem behavior. It may also focus on the severity or intensity of emotional distress and the thoughts that surround that experience.

Diagnosing and the DSM

A very specific outcome of an assessment for psychopathology can be determining whether the behavior meets the criteria for a psychological disorder. In this case, we make a distinction between the broader process of assessment and this focused task of the classification of behavior. As with many sciences, psychology has adopted a system of classification to name specific phenomena, in this case, problematic behaviors. The system that is currently used to classify abnormal behavior is the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM-5. The DSM-5 was developed by the American Psychiatric Association, the majority of whose members are trained medical doctors. Because the DSM-5 comes from a medical system, it classifies abnormal behavior based on symptoms that stand for some presumed underlying pathology. It can be noted that the DSM-5 is used primarily in the United States while the International Classification of Diseases (or ICD-10) is used more globally. Both the ICD-10 and DSM-5 use a symptom-based approach to classify abnormal behavior.

There are both strengths and weaknesses to using a medical model to define psychological problems. It is valuable and arguably necessary to have a consistent way to talk about psychological problems. If we did not, mental health professionals could have real problems communicating with each other. Creating a classification or taxonomic system allows researchers to investigate specific problems and gather scientific data.

The challenge with any taxonomy of psychological behavior lies with assuming that the label we use for one person means the same thing for another person. That is, one person’s extreme sadness (diagnosed as major depressive disorder) may be very different and even caused by very different things than another person’s extreme sadness. This is not necessarily the case in much of medicine. Appendicitis, for example, is the same problem from one person to another, and factors like the person’s history and current context may not matter in its diagnosis and treatment; in fact, the intervention for appendicitis will likely be consistent across the population.

That isn’t the case for psychological distress. Sadness that is caused by job loss may be very different in nature than that caused by the loss of a loved one, or the result of political oppression, or even from bullying at school. The intervention around that sadness would depend on the cause and the context of the individual. It is important to note that the diagnosis of a psychological disorder does not capture these differences. That being said, the DSM-5 (and ICD-10 worldwide) is the classification system that is used most frequently, and we will frame the next two chapters around this way of defining abnormal behavior.

In the DSM-5, psychological disorders are defined by specific criteria. Each disorder is assumed to be unique and has its own correspondingly unique course, outcome, and treatment. Remember that disorders are only diagnosed when the specific behaviors (labeled here as symptoms) either cause a subjective experience of distress or the behavior interferes with the individual’s social role functioning. Each disorder will have criteria for how long we expect it to occur (e.g., four weeks) and a number of symptoms that would have to occur to meet criteria for the disorder. For example, to be diagnosed with major depressive disorder, a person would need to show those behaviors for a minimum of two weeks and have five of nine of the listed symptoms (e.g., depressed or sad mood, loss of interest, changes in appetite, feelings of worthlessness).

There are over 150 distinct psychological disorders in DSM-5 (some counts put this over 260). The disorders are broadly organized into major categories like eating disorders, psychotic disorders, sexual disorders, and so on. The next chapter will focus on anxiety disorders (including trauma-related and obsessive-compulsive disorders). The following chapter will cover mood disorders and schizophrenia, a psychotic disorder defined as a major break from the experience of reality.

Theories of Pathology and Therapy for Disorders

Section Focus Question:

What are the most common treatment approaches today?

Key Terms:

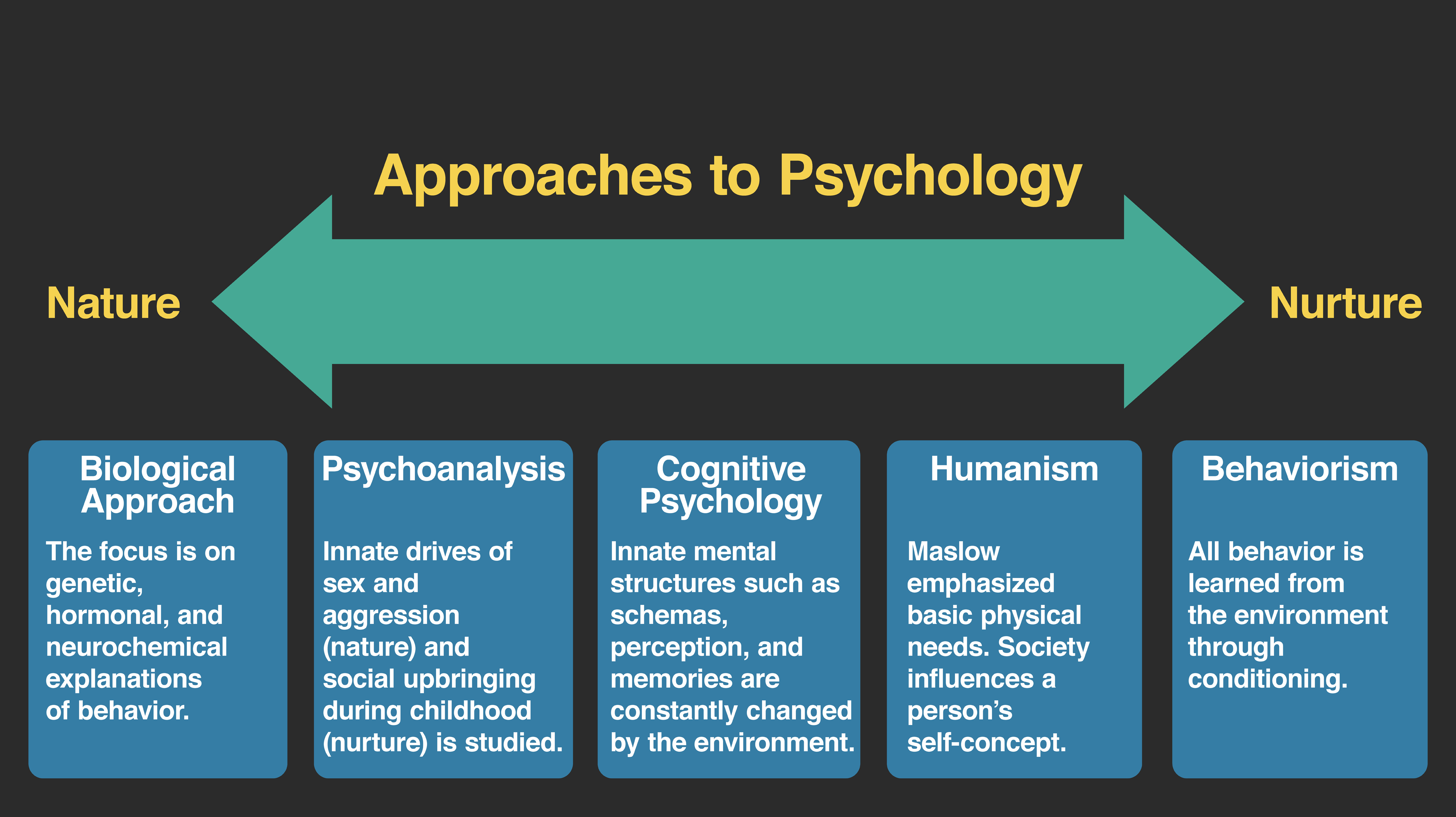

- Nature vs. nurture

- Drug effects

- Dysfunctional belief/negative thought

- Dysfunctional core beliefs

- Learned associations

- Operant conditioning

- Cognitive Behavior Therapy

- Dominance of CBT

Section Focus Question:

What are the most common treatment approaches today?

Key Terms:

It is important to remember that a diagnostic system is used for the classification or naming of psychological conditions. The DSM (and ICD) is intended to provide objective, measurable criteria for diagnosing disorders. Neither the DSM nor ICD discusses possible causes of these disorders, nor do they provide suggestions for psychological interventions or treatments. From a mental health practitioner’s perspective, the classification of a psychological disorder is useful only inasmuch as it helps provide some way to alleviate the problem.

A variety of psychological theories exist for why people experience abnormal behavior. Theories of psychopathology are important because they provide a blueprint to understanding the origin of the problem behavior and provide a way to alleviate that problem. It is important to remember that theories provide hypotheses about how the abnormal behavior originates. These hypotheses are valuable in psychopathology because they can give ideas about how the behavior might be changed. We understand these ideas as mechanisms of the problem (how the behavior comes about) and mechanisms of change (how to change the behavior).

Theories of psychopathology are numerous and range from Sigmund Freud’s classic psychoanalysis, focusing on the concept of the unconscious mind and early childhood attachment, to more modern approaches that focus on our thoughts and learned behaviors. The next two chapters go into more detail about specific psychological disorders and focus on contemporary treatments with scientific evidence for their effectiveness. These treatments fall under the broad heading of cognitive behavior therapy, and we will discuss both the cognitively focused interventions as well as those aimed at creating more effective behaviors.

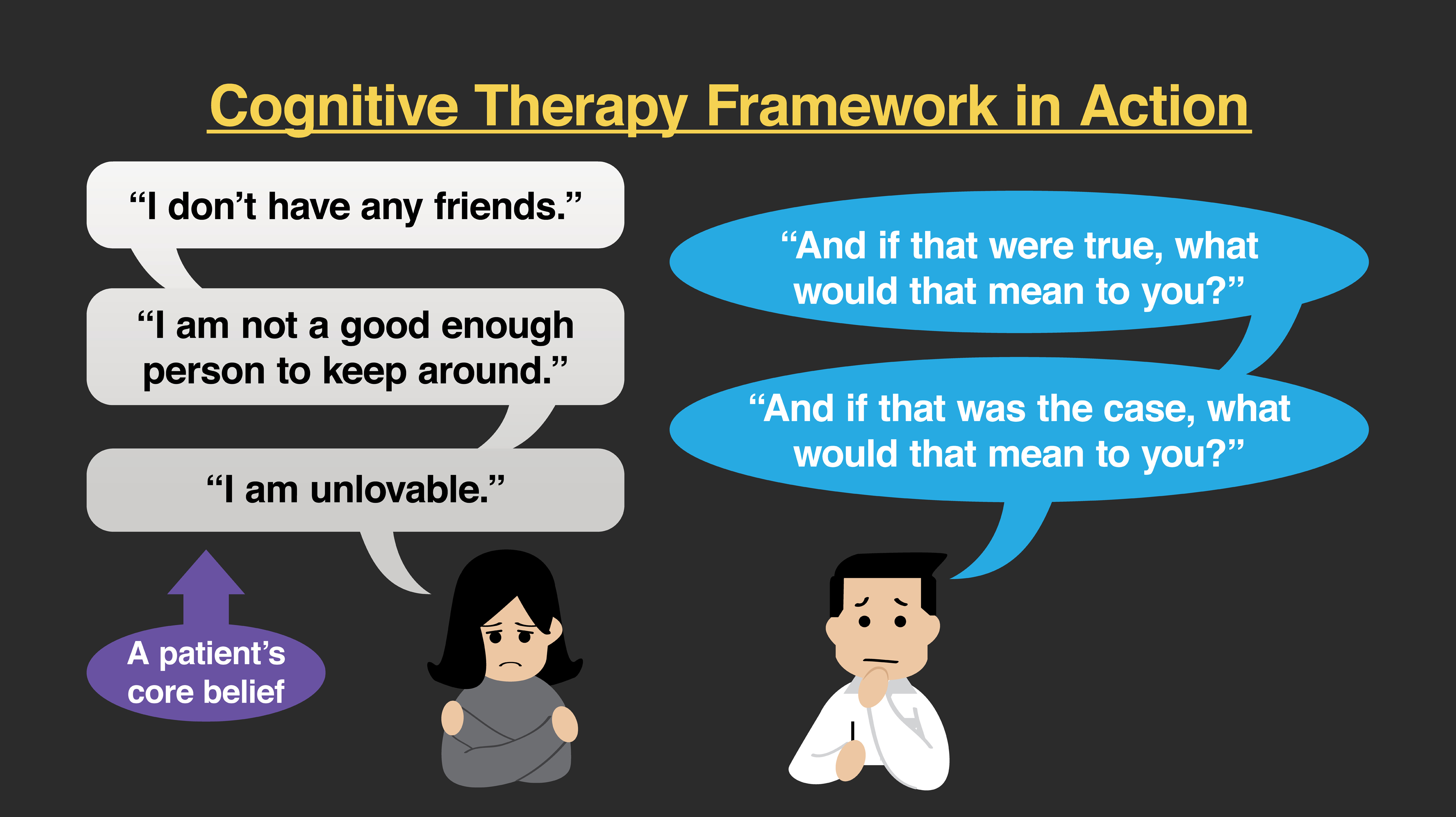

Cognitive Theory and Therapy

From a cognitive perspective abnormal behavior is caused by problematic thinking, specifically problems with core beliefs about others, the future, and oneself. When core beliefs cause difficulties, cognitive therapists regard these thoughts as dysfunctional core schemas. From a cognitive perspective, when these schemas are combined with the challenges that all humans have with making logical errors in their thinking (sometimes referred to as automatic thoughts or cognitive distortions) they produce abnormal behavior and emotional distress. The key is to notice that from a cognitive model, thoughts will cause the person to behave erroneously or feel distress.

Consider someone who is very sad. While sadness is a natural feeling that all people experience, from a cognitive therapy framework if that feeling is combined with a dysfunctional core schema, that person is more likely to be depressed. This person may have beliefs like, “I am unlovable,” or “I don’t deserve to be successful.” These dysfunctional beliefs can then be combined with negative automatic thoughts like “it’s all bad” or “I’m going to fail at this.” For a cognitive therapist, that combination of dysfunctional core beliefs and automatic thoughts will cause the person to feel depressed. They would also cause the person to withdraw from people, to want to stay in bed all day, or to engage in other behaviors we associate with the diagnosis of major depressive disorder.

Given that the mechanism of the problem here is problematic thoughts, the mechanism of change for cognitive therapists is to change those dysfunctional schemas by replacing them with more accurate beliefs. The therapist helps the client recognize his or her cognitive distortions or automatic thoughts, to challenge them, and then to replace them. In our example of the person who is depressed, the therapist would ask the client to identify his or her thoughts when feeling sad. The client and therapist work collaboratively to find what the core belief is about the person’s self. If the client and therapist arrived at the schema, “I am unlovable,” the therapist would look for evidence where that is not true and help the client recognize that he or she has been loved or cared for in the past and there are very good qualities about that person that others could find loveable. The therapist might suggest an alternative schema like, “I have challenges like everyone, but I am a respectable person worthy of love.”

It is important to note that the therapist will look to replace dysfunctional core beliefs with more accurate ones, not just happier-sounding thoughts. If a client had a dysfunctional core schema that “the world is unsafe” following a traumatic event, the therapist would not want the client to develop a belief that the world is always safe. However, the therapist would want the client to develop a more accurate schema such as, “the world has both safe situations and those that can be unsafe.” The client can learn to notice when it is better to be more thoughtful and more vigilant about one’s safety while also learning that not every situation requires being on guard at all times. Ultimately, from a cognitive therapy perspective, altering the core schema will produce more effective behaviors, and the client will feel better.

Behavioral Theory and Therapy

A behavioral framework approaches human suffering by examining how behavior was learned and what maintains that behavior. For psychopathology, a behavioral therapist focuses on those behaviors that are less effective in helping the individual reach his or her goals. From this approach, behaviors can be less effective for a variety of reasons. First, the client may have learned ways of doing things that no longer work as well. For example, a student may have learned one way to study for tests in high school that then have to be modified for college to be effective. Other times, a person may just not have learned a skill that is required in a new situation. For example, being in a long-term relationship often requires multiple skills that need to be developed but are rarely taught.

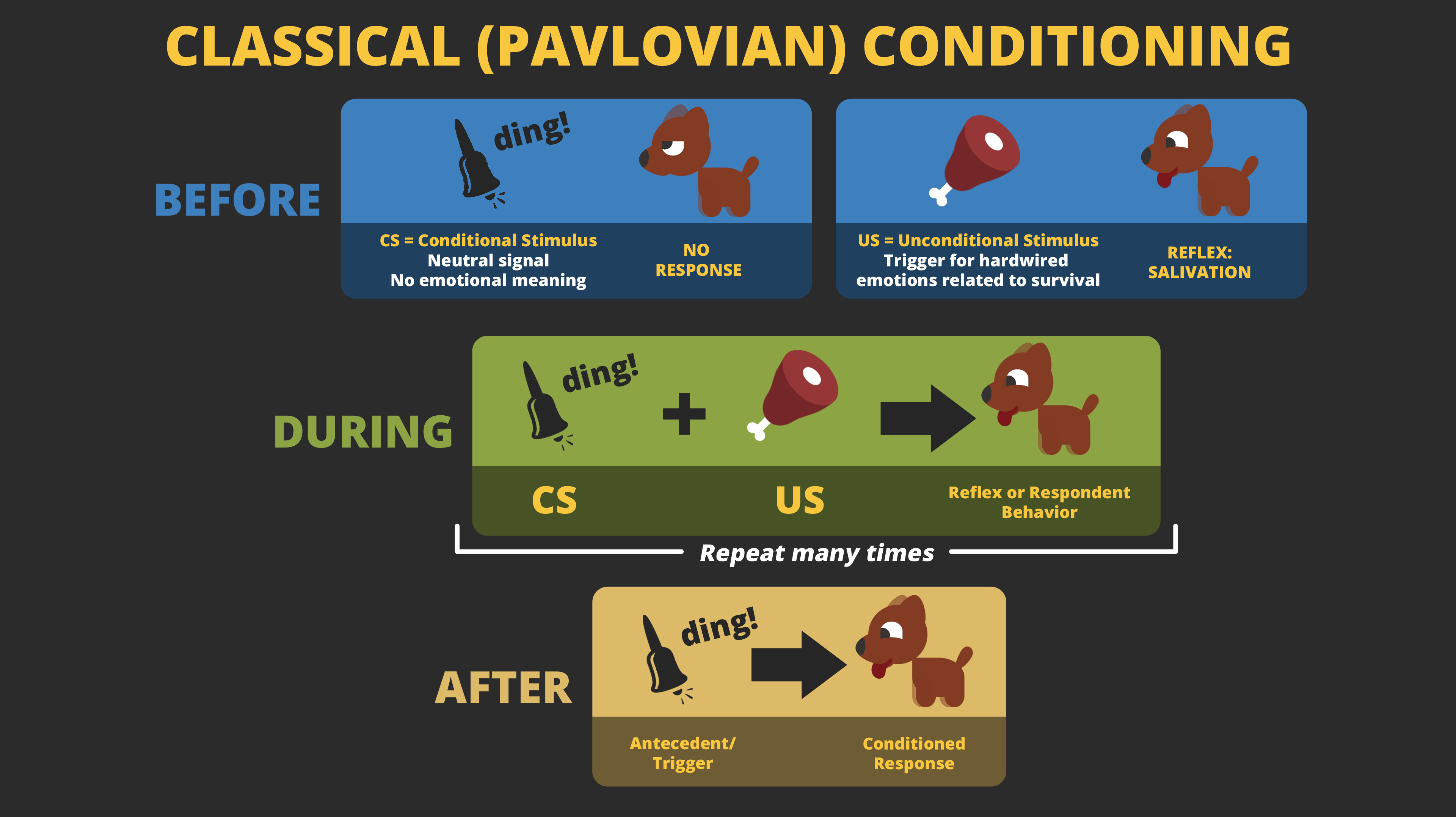

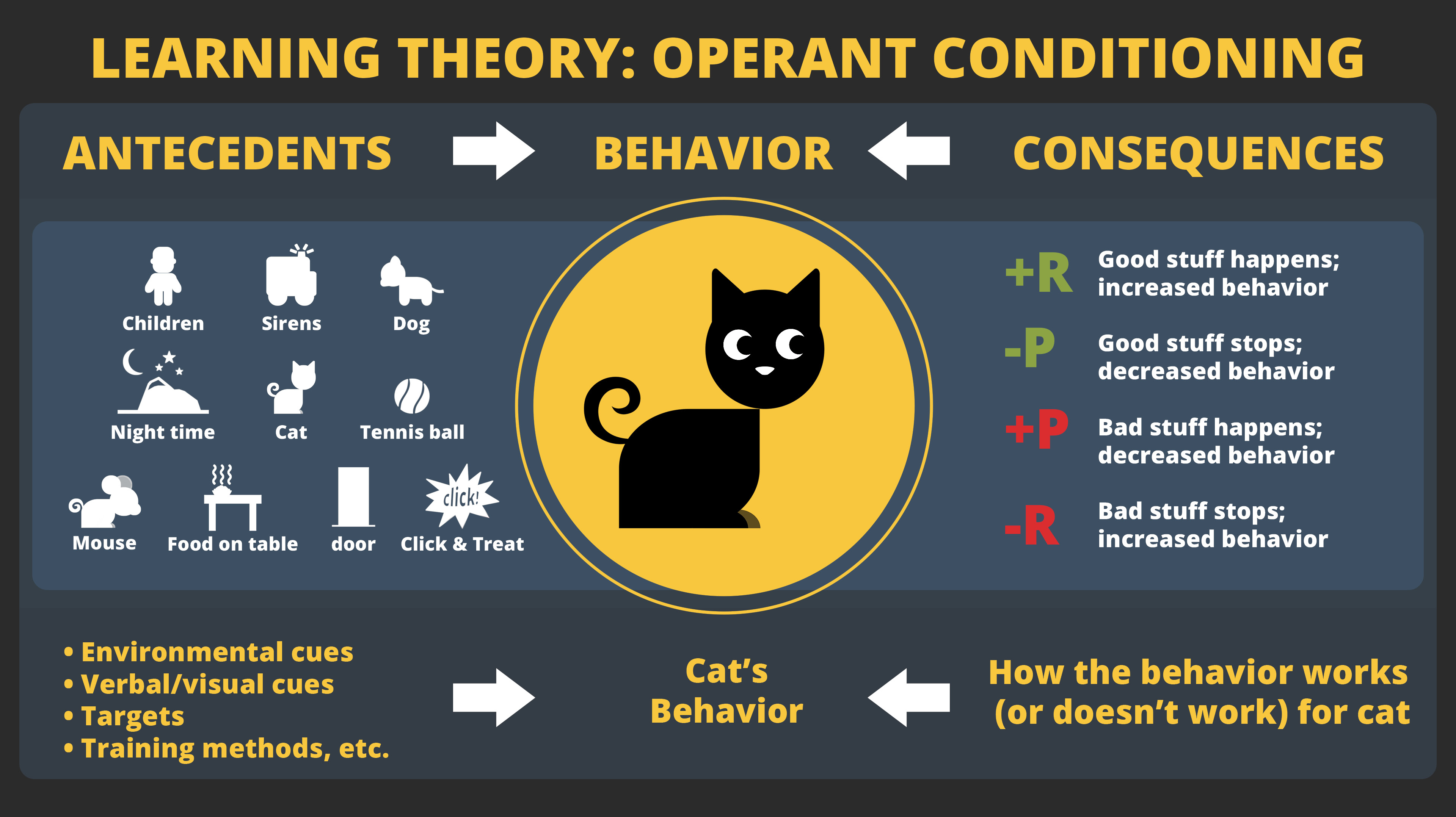

The behavior therapist understands the mechanism of the problem using basic learning principles. There are associative processes of learning found in classical conditioning, and there are operant principles where a behavior produces a consequence in the environment. For example, we may be afraid of bees because a bee stung us in the past. From a classical conditioning perspective, the unconditioned stimulus (bee sting) is paired with the unconditioned response (pain, fear, and so on). The conditioned stimuli associated with the pain of the sting in that moment include all of the properties of the bee (the sight, sound, and feel of the bee on our skin). Those conditioned stimuli (e.g., seeing the bee) will make us anxious in anticipation of the pain of a sting. This is the way classical conditioning is used to explain how many phobias are acquired.

The principles of operant conditioning are used to explain why the person would run from a bee or avoid situations where bees might exist when he or she is anxious. In this case, the bee and the anxiety give rise to the response of running or escaping from the bee. Once the bee is no longer around, there is a decrease in the aversive experience of anxiety. Running from the bee decreases that aversive state and the running response is negatively reinforced and is more likely to occur in the future.

Negatively reinforced behavior is called escape and avoidance learning. If we encounter a scary or aversive situation, and we leave that situation, that is considered an escape response. If we are able to prevent that anxious or aversive situation from occurring at all, it is considered an avoidance response. It is important to remember that no behavior from a learning or behavioral perspective is inherently psychopathological; behavior is simply more or less effective in helping a person meet a goal. If a person were allergic to bee stings and ran from a bee, then that would be a very effective (and healthy!) response. If a different person avoided going to parks for fear of seeing a bee, and that person enjoyed the outdoors, then that avoidance behavior may prevent him or her from living the values they have chosen.

From a behavioral perspective the mechanism of change, the way to help relieve suffering, is to learn more effective behaviors. This happens through directly instructing a new response, through role-playing a new behavior, and through trial and error – just trying to see what might work differently. Often times there is a considerable amount of exposure and extinction that occurs. These principles require a person to experience the conditioned stimulus or situations that give rise to anxiety, sadness, or other emotions in a safe environment and not to engage in escape or avoidance behaviors that have been so strongly reinforced. This ultimately extinguishes the classically conditioned aversions, and the person learns new more effective ways to encounter and engage difficult situations and emotional experiences. We will discuss exposure therapy in more detail in the next chapter.

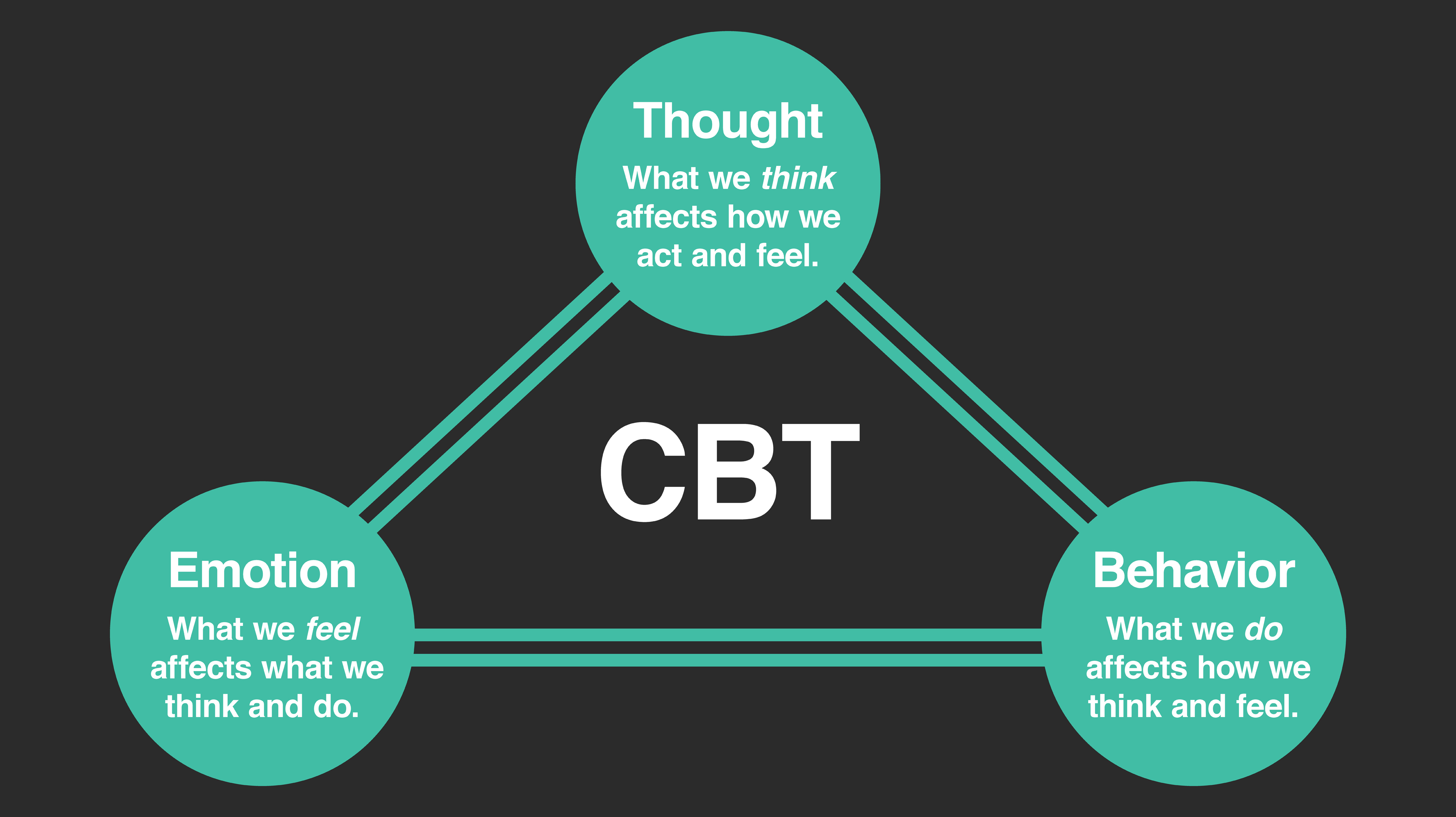

Cognitive Behavior Therapy

Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) is one of the most common interventions for psychological disorders. It is a combination of working on problems from a cognitive approach by addressing dysfunctional thoughts and a behavioral approach through exposure and learning more effective ways to respond. CBT is used for many psychological disorders and has a great deal of research to support its effectiveness. We will see in the next chapters that CBT is used to help problems like posttraumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and major depressive disorder. The list of problems that CBT is effective in treating grows every year, making it the dominant form of evidence-based psychological treatment for behavioral problems.