Concepts

Note to students: The best preparation for taking the reading quiz is to pay close attention to the key terms as you read. Each question in the question banks is directly linked to these key terms and phrases.

Chapter Focus Question:

Why are scientists, psychologists, and philosophers intrigued by the idea of “concept,” and how have these disciplines tried to articulate what “concept” is?

- Concept

- Definitional view of concept

- Gettier problem

- Digital computer view of the brain

- David Marr’s tri-level hypothesis

- Mind/Brain separation

- Input/output neural systems

- Embodied cognition

- Embodied simulation hypothesis

Section Focus Question:

How has the notion of “concept” changed over time, and how has embodied cognition affected scientific studies?

Key Terms:

When you see a dog, you know what you’re seeing. How do you know that a dog is a dog, and not a car, or a turnip, or another animal that looks similar to a dog, like a hyena?

The simple answer is that you have a concept, DOG, which allows you recognize dogs and distinguish them from non-dogs. Behind this simple answer, however, lies a set of complex questions that scholars have been trying to answer for over two centuries: What is a concept, and how do people acquire the concepts that populate their minds?

Most cognitive scientists agree that concepts are the building blocks of thoughts, but there is little agreement about what concepts are made of, or how they are learned, stored, and used. The sections below review some of the most influential theories of concepts in the cognitive sciences, and the challenges they face.

Concepts as definitions

The “definitional” or “classical” view of concepts seems so intuitive that no major alternatives were articulated from the time of the ancient Greeks until the mid-20th century. On this view, concepts are defined in our minds much like words are defined in a dictionary. These definitions provide the necessary and sufficient conditions by which a thing in the world can be categorized as corresponding to a particular concept.

One example of a concept that seems amenable to definition is BACHELOR. It is common for researchers to designate concepts in capital letters, to distinguish concepts from the things in the world they correspond to (i.e, bachelors), and from the words that label them (i.e., the word “bachelor”). Arguably, the concept BACHELOR has three necessary and sufficient features. To be a bachelor, one must be (1) a human male, (2) unmarried, and (3) of marriageable age. In theory, anything that meets these three conditions is a bachelor; anything that does not meet all three of them is not. In practice, do these conditions enable people to pick out all and only the bachelors in the world?

The definition appears at first to do some useful work: It explains why Barack Obama was a bachelor before he got married but Michelle Obama was not, and why preschool boys are not considered bachelors. But the theory runs into problems when it comes to many men who fit the definition perfectly: Is the Pope a bachelor? How about a 90-year-old widow, or a man who lives with his partner in a long-term monogamous relationship but is not married? Although these men have all of the necessary and sufficient conditions for bachelorhood, most people would hesitate to call them bachelors.

Is it possible that the definitional theory only applies to concepts that are formally defined, such as those used by logicians or philosophers? This proposal does not appear to rescue the definitional theory. In the early 20th century, many philosophers were convinced that a satisfactory definition of KNOWLEDGE had been found: Having knowledge meant having a belief that is both true and justified (the latter criterion was intended to rule out instances of having a belief that is true, but only by coincidence). In the 1960s, however, the philosopher Edmund Gettier constructed a scenario that showed this definition to be inadequate.

Imagine that you believe your friend Joe drives a green American car. You have a clear justification for this belief: The last time you saw Joe he was driving his green Chevrolet. Unbeknownst to you, however, Joe recently traded in his green Chevy for a green Ford (another brand of American car). According to the accepted definition of KNOWLEDGE, you know that Joe drives a green American car. Your belief that Joe drives a green American car is both justified and true, thus it satisfies the definition of the concept of KNOWLEDGE. And yet, you don’t actually know what car Joe drives! You have the wrong car in mind, and therefore the justification for your belief is problematic, and your “knowledge” would not allow you to correctly identify Joe’s car, or to distinguish it from cars that don’t belong to Joe. The Gettier problem illustrates why “justified true belief” must be rejected as a definition of knowledge.

No unproblematic definition of KNOWLEDGE has been found. Many theorists would argue that the problem does not lie in any particular definition, or any particular concept. Rather, contrary to centuries of common sense theorizing, it appears that few concepts have clear definitions. Therefore, definitions cannot provide an adequate account of human concepts.

- Definition vs. prototype

- Prototypical vs. marginal

- Required traits vs. prototypical traits

- Prototypical features

- Eleanor Rosch/concepts as prototypes

- Jerry Fodor/combinable concepts

- Role of definition vs.error-prone concepts

- Hybrid theory of concept

- Hybrid theory weaknesses

Section Focus Question:

What reasons are there to question the theory of concept-as-a-prototype and the hybrid theory of concepts?

Key Terms:

Concepts as prototypes

Experiments by the psychologist Eleanor Rosch in the early 1970s revealed another problem with the definitional view of concepts, and gave rise to the view that concepts may be prototypes rather than definitions.

Imagine a standard definition of a bird: for example, an animal that is covered with feathers, lays eggs, and has wings. To rule out the possibility of bird-like imposters, we could add that it must have DNA that allows it to breed with other birds. A robin meets all of these criteria; so does a penguin. Yet, they are not equally “birdy” in people’s minds. When asked to verify sentences like “A robin is a bird” and “A penguin is a bird,” people generally judge them both to be true, but they are quicker to make judgments of more canonical birds. This result is incompatible with a definitional view of concepts, since canonical and non-canonical birds are equally consistent with any reasonable definition of birds.

The difference in judgment times does not arise from any difference in how completely robins and penguins exhibit some defining set of features, but rather in how many prototypical features of birds these animals have. In addition to features like feathers, which are sine qua non for birds, robins also have attributes like “small in size,” and “lives in trees,” which are prototypical of birds, but not required. The more prototypical features a bird has, the birdier it seems. This principle holds for many other categories as well: Apples are prototypical fruits (sweet in taste, eaten for dessert), whereas olives are marginal fruits; Football is a prototypical sport (requires running, played by teams), whereas weightlifting is a marginal sport, etc.

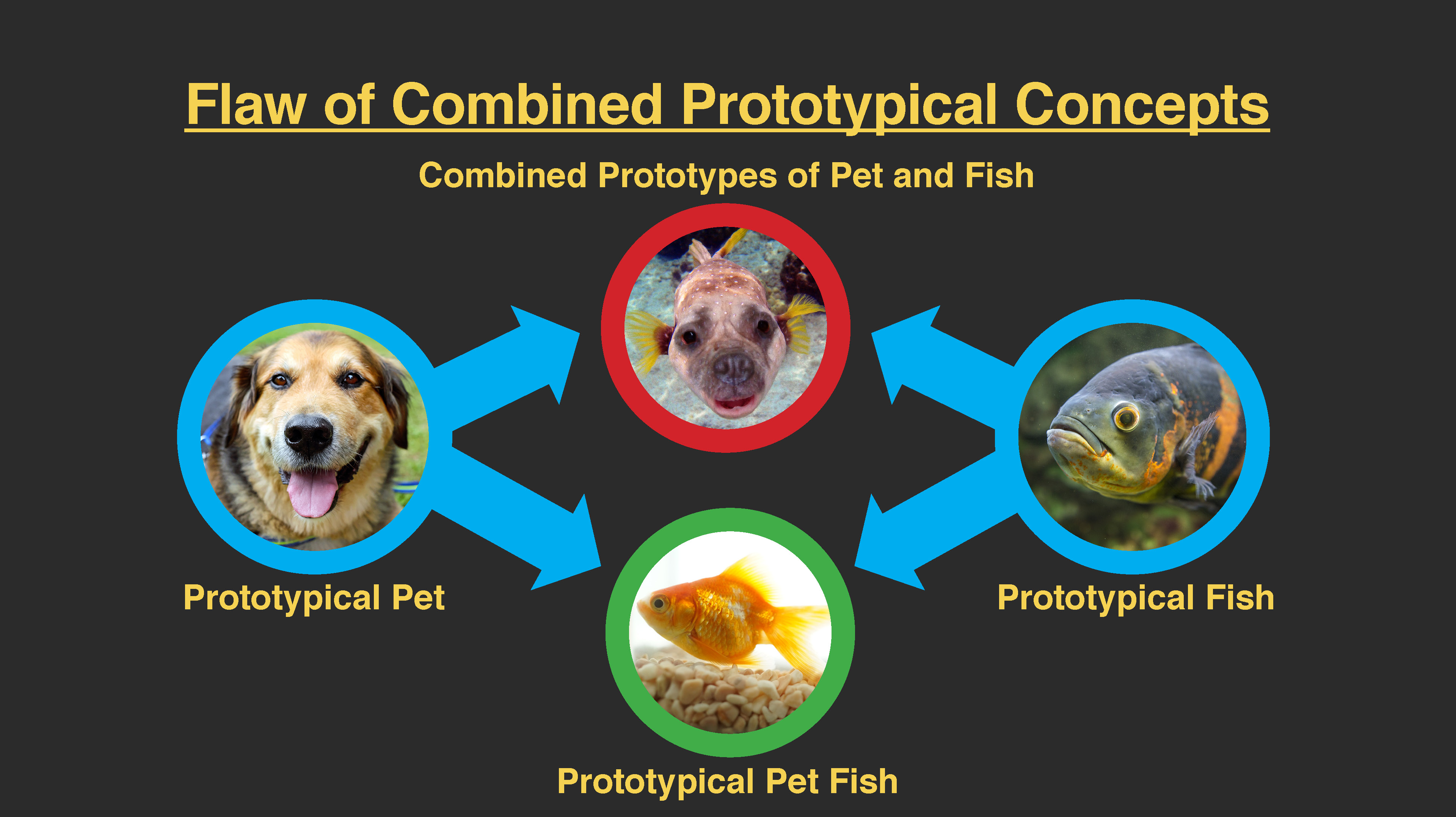

So, are human concepts prototypes? The philosopher Jerry Fodor offered one of the most influential critiques of this view based on the idea that concepts must be combinable. Compound nouns like “houseboat” and “pet fish” are common in many languages, and they label concepts that are composed of the concepts named by their constituent nouns: a houseboat is a boat you can live on; a pet fish is a fish that’s a pet. But imagine what would happen if you tried to compose a prototypical pet fish out of a prototypical pet (e.g., a dog or cat) plus a plus a prototypical fish (e.g., a trout or sunfish). The prototypical pet is likely to be four-legged, furry, cuddly, etc. The prototypical fish is scaly, wet, and delicious when fried. When we combine the pet prototype with the fish prototype we do not arrive at a prototypical pet fish (e.g., a goldfish in a bowl). Instead we get a furry, four-legged, finned monstrosity.

Fodor’s “pet fish” argument, among others, convinced many researchers that although concepts exhibit prototype-like structure, prototype theory is unlikely to provide an adequate description of what concepts are.

- Atomic view of concept

- Conceptual atomism

- Plato’s theory of concepts

- Modern theory of innate concepts

- Flaws of atomic conceptualism

- Concepts and words

- Stability of concepts

- Concepts and context

Section Focus Question:

How does the atomic view of concepts explain newly created ideas, and what roles do language and context play in the stability of concepts?

Key Terms:

Hybrid theory of concepts

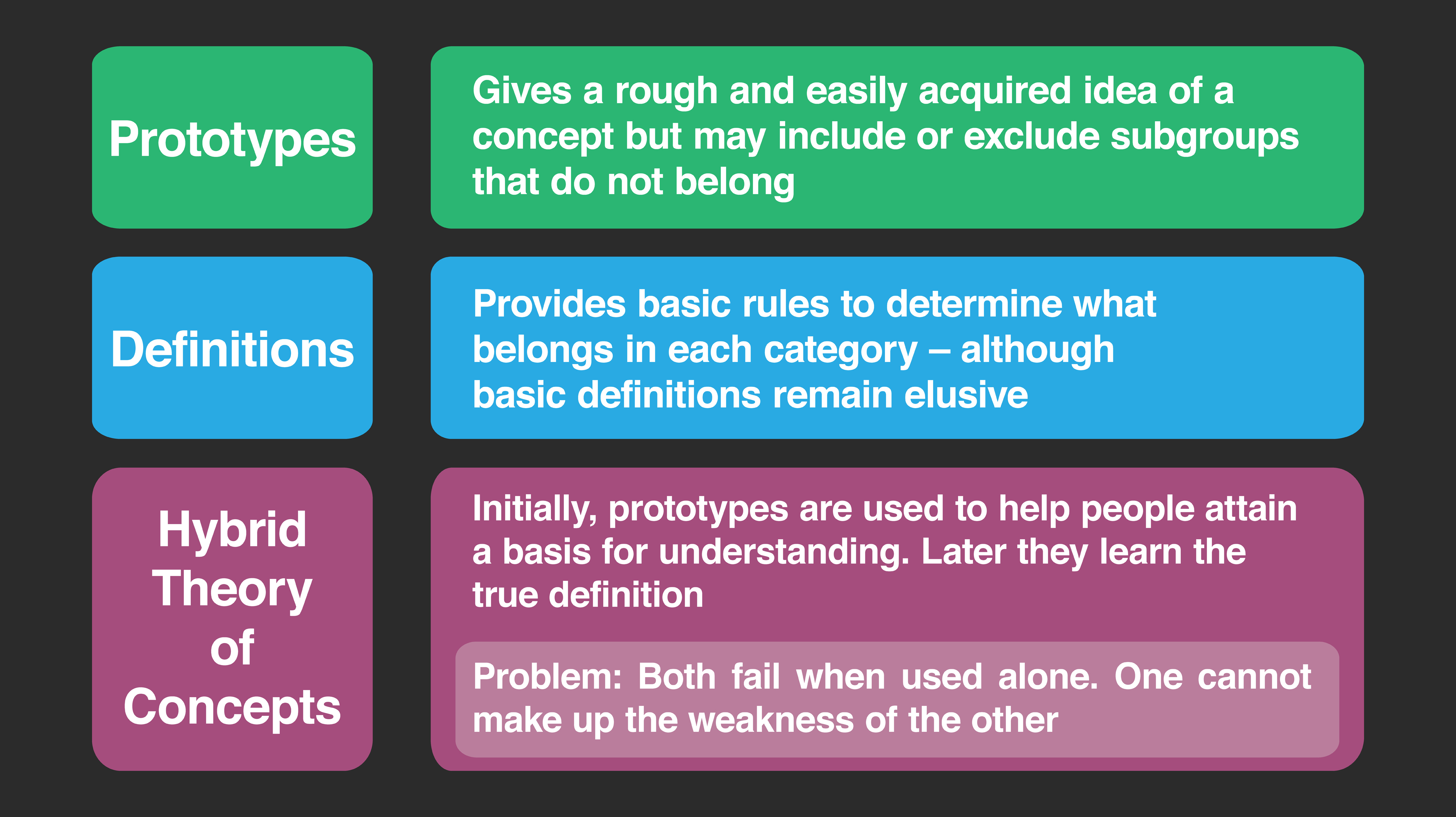

Could a combination of the definitional theory and the prototype theory provide an adequate account of human concepts? Some scholars have suggested that people use prototypes in some contexts and definitions in others, and that in combination these two theories are sufficient to explain how we learn and use concepts.

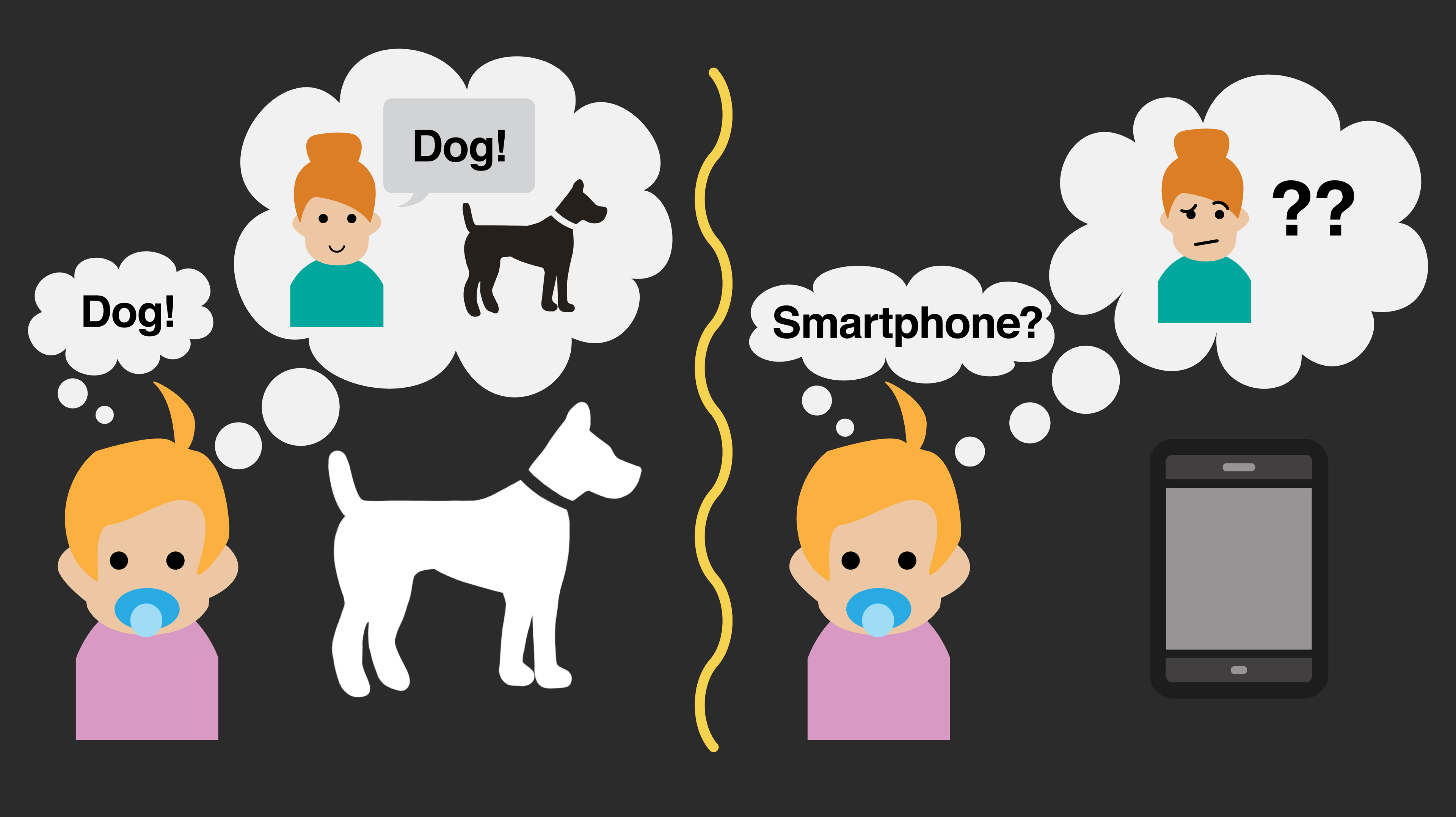

Consider the challenge a child faces when trying to acquire the concept GRANDMOTHER. For this concept, and most others, children succeed in learning and using the concept even though nobody ever teaches them a formal definition (e.g., a grandmother is a female parent of a parent). How? Perhaps by identifying a grandmother prototype. On the basis of their experience with their own grandmothers and others, children could infer that grandmothers have prototypical properties like being female, elderly, kindly toward children, good at baking, etc. This prototype could allow them to begin spotting people who are likely to be grandmothers, and to interact with grandmothers in socially appropriate ways (e.g., give them hugs, eat the cookies they bake).

A prototype would not be sufficient, however, for the most important role that concepts are supposed to play in our mental lives: allowing us to identify grandmothers in the world and distinguish them from the non-grandmothers. On the basis of the GRANDMOTHER prototype, it would be impossible to tell grandmothers apart from great aunts or kind elderly neighbors who never had children of their own. Moreover, the prototype would fail to identify all of the non-prototypical grandmothers in the world, some of whom are Army drill sergeants or scantily clad rock stars.

According to the hybrid theory, in order to exclude aunts and include rock-star grandmas, a child must eventually learn a definition for GRANDMOTHER. Although prototypes could help children acquire an initial set of (error-prone) concepts, it seems that definitions are needed to do the important work of sorting the world into categories.

Yet, as discussed above, after centuries of searching for definitions, few if any have been found. Thus, the hybrid theory of concepts fails due to the weaknesses of two theories it seeks to combine: Prototypes cannot perform the most basic functions of concepts (picking out all and only the bachelors or grandmothers in the world), and definitions don’t seem to exist.

Conceptual atomism

Both the definitional and prototype views assume that a concept is composed of some set of features or properties. An alternative view, however, is that concepts are “atomic,” meaning that they cannot be broken down into constituent parts. On this view, one’s concept of DOG is not constructed from properties like “living” and “four-legged” – DOG is simply a unitary piece of knowledge that corresponds in a lawful way to the category of dogs in the world. If the concept DOG is not composed of the observable features of dogs, then it is difficult to imagine how children could learn the concept. This concern motivates proponents of “conceptual atomism” to conclude that most of the atoms of knowledge in our minds are not learned: They are innate.

The idea that most (if not all) of our concepts are innate has a long history. Several of Plato’s dialogues concern the origin of our knowledge. After exploring multiple possible origins, Plato concluded that we do not learn our concepts at all. Rather, in between lives, our souls exist in a bodiless form, and we have perfect knowledge of everything. At the moment of birth, however, this knowledge is forgotten. What we call “learning,” according to Plato, is really a process of remembering the knowledge we had in previous incarnations of our soul. The modern explanation of how concepts could be innate does not rely on reincarnation, but rather on evolution. We had “knowledge” prior to our birth in the form of information encoded in the human genome, which has been handed down over evolutionary time.

Conceptual atomism offers potential solutions to some big problems with other theories of concepts. How do we make a list of what pieces of information are included in a concept’s definition? If concepts are atomic, then we don’t have to: Concepts don’t need to be defined in terms of their parts. How do concepts change their constellation of features when they combine (e.g., PET + FISH)? If they are atomic then they don’t have to change because atomic concepts have no features. How do we learn atomic concepts? We don’t!

The most problematic aspect of conceptual atomism is the claim that all (or most) concepts are innate. The idea that some knowledge is been encoded in the human genome is vague, but it is not implausible. Infants appear to be born with some sophisticated knowledge. Beyond their knowledge of how to perform actions (e.g., cough, cry, grasp), infants also appear to have some conceptual knowledge about the physical world (e.g., they expect objects to fall downward when they are not supported), and about numbers (e.g., they can distinguish two objects from three objects). It is possible that some knowledge of the natural world is innate, particularly if that knowledge is relevant for survival and reproduction.

It is implausible, however, that all of our knowledge is innate. How could our concepts of recent inventions like SMARTPHONES, BLOGGING, and TWERKING have come from our genome? Although conceptual atomism has some adherents, it has been dismissed by many scholars on the grounds that (a) atomism does not provide any clear theory of how concepts can be learned, and (b) at least some concepts clearly are learned – at least concepts of things that came into existence during our lifetime, which includes numerous ideas and objects that we use every day.

Rethinking the concept of concepts

Do we need the concept of CONCEPT in order to build a scientific understanding of the mind? Since the time of William James, a founder of experimental psychology in the 19th century, doubts have been raised about the scientific utility of this notion. It is possible that the existence of concepts is, at least in part, an illusion – created partly by the existence of words. Words are, in many ways, the same every time we use them. The written forms of words are especially stable: Once the word “dog” is printed on a page, it will look identical every time we look at it. It is natural to assume that this stable symbol on the page corresponds to some stable concept in our minds.

But the stability of concepts may be an illusion. A given word may correspond to a different pattern of activity in our minds every time we use it. Imagine the constellation of knowledge that you activate when you hear “dog” in the context of (a) a Great Dane, (b) a Chihuahua, (c) your family’s first pet dog, (d) your family’s second pet dog, (e) a stuffed toy dog (f) ketchup, relish, and a tube-shaped bun. Perhaps the best characterization of our concept DOG is: a dynamic pattern of information that becomes active in long-term memory when we see dog, or hear the word “dog,” or need to think about dogs. This pattern of information is likely to be strongly dependent on the context in which we encounter the word (or other cue) that prompts us to think DOG thoughts. Therefore, the pattern may never be the same twice, within or between individual people.

Understanding concepts in this dynamic way requires understanding how words and other cues activate information in our long-term store of knowledge. In this view, the study of concepts is inseparable from the study of language and memory.