The Great Crash

Note to students: The best preparation for taking the reading quiz is to pay close attention to the key terms as you read. Each question in the question banks is directly linked to these key terms and phrases.

Chapter Focus Question:

What was “the Great Crash,” and how does it relate to “the Great Depression?”

- Credit and Advertising during the 1920s

- The decade of the 1920s and prosperity

- Decline of prices paid to farmers for goods

- Advertising Credit and mass consumption

- Advertising an affordability of goods

- Americans and credit in the 1920s

Section Focus Question:

What did the phrase “new era prosperity” mean, and why was it a false promise even before the Great Crash?

Key Terms:

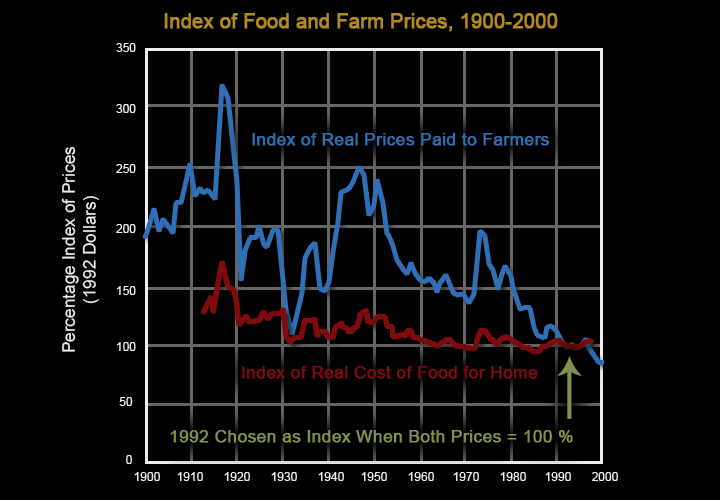

Country folks had much to resent about city folks in the 1920s. Besides the clash of values and lifestyles, there was a tremendous economic disparity between the fates of rural and urban America in a decade that was supposed to be prosperous for all. Farm prices crashed precipitously after World War I, leaving many farmers high and dry because they had borrowed heavily to expand operations during the war. Agricultural surpluses plagued the farm sector throughout the 1920s. Farm prices stayed low and farmers never got a chance to participate in New Era prosperity

Perhaps the ultimate insult to farmers was the ceaseless migration of their own sons and daughters away from rural areas and toward the cities. In 1920, the US Census Bureau announced that a majority of Americans lived in towns and cities for the first time ever, and the nation's urban population grew tremendously in the following decade, despite immigration restriction.

The reason was simple: children of the farm voted with their feet, running away from the traditional virtues of country life and running toward the modern excitements of city life. But they also left home out of sheer necessity. They came for jobs in the cities, because farm life was wracked with debt, poverty, and isolation even in the supposedly prosperous 1920s.

Another sign that not all was well with the US economy in this decade was the explosion of consumer credit and advertising. Credit in the form of "buy now, pay later" installment plans was necessary for more and more consumers to purchase the new automobiles, radios, appliances, vacations, and other trappings of modern life that would otherwise be financially out of reach. Advertising was equally necessary to persuade consumers to buy what they knew they could not afford. New Era prosperity relied on credit and advertising to stoke the engines of mass consumption.

The underlying problem was the nation's severe inequality of income. Republican policies under the Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover administrations favored millionaires and corporations, which fared supremely well, but millions of workers, farmers, and poor folks did not. A handful of rich people, however prosperous, could never purchase enough Model T Fords and RCA radios to keep the assembly lines rolling and this is why a crisis of under-consumption was looming by decade's end. All that remained to pop the balloon of New Era prosperity was a high profile disaster — the Great Crash.

- 1929 stock prices and borrowed money

- Speculation aside from the stock market

- Concentration of wealth and spending

- Investment sectors and prosperity

- Private debts in the 1920s

Section Focus Question:

According to Glen Gendzel, what kinds of economic problems and business practices led to the Great Crash of 1929?

Key Terms:

The stock market rose dramatically in the late 1920s. Prices doubled between 1925 and 1928, then doubled again in 1929. Republican presidents and their business allies pointed to Wall Street's boom as self-evident proof of the wisdom of their economic stewardship. But in fact, the stock market bubble of the late 1920s was the last and biggest expression of a reckless speculative spirit that pervaded the whole decade.

New Era prosperity was never as broadly based, universally shared, or permanently secure as promised. It was highly concentrated in a handful of booming industries such as automobiles, construction, and real estate. Florida real estate underwent a notable boom-and-bust cycle early in the decade, but when that ended in 1925, speculators turned to the stock market. After all, with politicians and businessmen crowing in unison about permanent prosperity and the end of poverty, future profits seemed assured.

Millions of Americans who previously had not owned stocks plunged into the market in the late 1920s. Many of them borrowed money to buy over $20 billion in stocks "on margin." They opened brokerage accounts at branch offices of Wall Street firms, which proliferated across the country to accommodate all the new demand for stocks. Stories of common people who "made a killing" in the market drew in more and more eager suckers. New Era cheerleaders in politics and business declared that spreading stock ownership among the masses meant prosperity was for real, when in fact it only meant that any market decline would have devastatingly widespread effects.

- The economic downward spiral and the workplace

- Vindication of progressivism and the New Deal of the 1930s

- Decline of farms and move to the city

- Reasons for panic sales of stocks

- The stock market and the use of credit

- Meaning of Black Tuesday

- Percentage of value lost in the great crash

- The psychological impact of the great depression

- Federal Reserve Board and interest rates

- Duration of the Jazz Age

- Overarching reasons for the Great Depression

- President Wilson's exoneration

- Repudiation of politics of the 1920s and New Deal

Section Focus Question:

What caused the Great Crash to turn into a long-term and devastating depression instead of a short-lived recession?

Key Terms:

The inevitable market correction came in the fall of 1929. Most business sectors were at a standstill as capital badly needed for credit and new investment was sucked into the stock market. Prices leveled off and stagnated in September, triggering a slowly growing panic among investors and bankers that stocks might not continue gaining value in the future. Such a prospect would spell disaster for anyone who had borrowed money to buy stocks or who had loaned money for the same purpose.

Hence waves of selling began to surge through the market in October, culminating in a general panic near the end of the month. New York bankers stepped in and temporarily halted the market collapse with infusions of capital, but it was not enough. The near total lack of government regulation over Wall Street meant that the Great Crash was destined to play itself out in a free market free fall. By November 1929, the stock market had lost about 40 percent of its value. Prices fell even further over the next three years, until ultimately $75 billion in wealth was wiped out.

President Herbert Hoover took office early in 1929 promising that the future was "bright with hope," but by the end of the year he was nervously urging Americans not to panic. The fundamental economy was sound, the president insisted, despite the Great Crash. But Hoover's faith in business self-regulation without interference from government now betrayed him as the economy dissolved into the Great Depression.

Workers, faced with layoffs and wage cuts, ceased consuming. Businessmen, faced with declining demand, ceased investing. Factory owners, without new orders, laid off more workers.The spiral of depression wore on. Some economists blame the Federal Reserve Board for turning the Great Crash into the Great Depression through maladroit and clumsy manipulation of interest rates.

But at the time, the psychic impact of the much-publicized stock market collapse was so great that few questioned whether it had triggered a general economic crisis. Even though the vast majority of Americans owned no stocks, the country had learned to look to Wall Street as the nation's economic barometer and as the great symbol of New Era prosperity. When it crashed, so did the investor and consumer confidence necessary for continued prosperity. This meant the larger economy beyond Wall Street was doomed.

As the Jazz Age came to a close, most Americans saw the deepening economic crisis as an unmistakable rebuke to Republican conservatives and their big business allies who, by dismantling the progressive regulatory state, had invited a business disaster. This commonplace understanding of the significance of the Great Crash became clear in the next few election cycles, when Americans voted decisively against Republican conservatives and in favor of new experiments in government regulation under liberal Democrats.

In this sense, the New Deal of the 1930s would represent a vindication of progressivism and a repudiation of the 1920s. Likewise, in the following decade, when the United States became embroiled in World War II, most Americans developed a new appreciation for Woodrow Wilson. They acknowledged him as a prophet without honor in his own country who had been right all along about the need for US global leadership. Belatedly, Americans embraced collective security and helped create the United Nations, reversing decisions made in the aftermath of World War I. It was a shame that these realizations had not dawned sooner, before the Great Depression and World War II forced them upon Americans at the cost of untold misery, expense, and bloodshed.