Rise of the Cotton Economy and the Expansion of Slavery

Note to students: The best preparation for taking the reading quiz is to pay close attention to the key terms as you read. Each question in the question banks is directly linked to these key terms and phrases.

Chapter Focus Question:

How important was cotton to the economy of the South and to the continuance of slavery?

- Price of slaves

- Short- and long-staple cotton

- Increase in cotton production

- William Lloyd Garrison

- Removal of the Cherokee

- Thomas Nast

- The invention of the cotton gin

- Cotton as a valuable export

Section Focus Question:

How was the cotton economy created in the South?

Key Terms:

The Civil War proved, contrary to Hammond's prediction, that cotton hegemony was insufficient on its own to give the South the wherewithal to win. It could not, as Hammond believed, "raise, equip, and maintain in the field, a larger army than any Power of the earth can send against her, and an army of soldiers — men brought up on horseback, with guns in their hand." While in 1858 the South's population had surpassed by some 60 percent the entire white population of the 13 colonies at the time of the American Revolution, the northern population had grown even more.

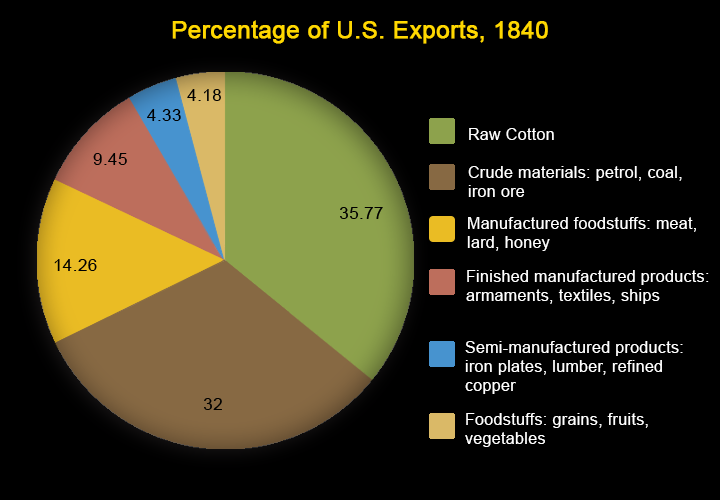

But Hammond was not wrong about cotton's place in the US and world economy. By 1815 cotton was already the nation's most valuable export and by 1840 worth more than all other US exports combined. The invention of the cotton gin played a major role in this development, making possible the commercial cotton cultivation of short-staple, green-seed cotton. Unlike the profitable long-staple, sea-island cotton, short staple cotton could be grown inland. Before the development and perfection of a cotton gin that could separate the seed from the cotton fibers, however, it had not been commercially viable.

By the mid-19th century, cultivation of both types of cotton stretched from the coastal and Piedmont regions of the Carolinas and Georgia to the rich black prairie lands of Alabama and Mississippi and the alluvial river bottoms of Louisiana, Mississippi and Arkansas. By 1860, the average value of slaveholdings was $9,400, a nearly 100 percent increase from about $4,800 in 1850. The Mississippi River delta, not the South Carolina Sea Islands or Virginia tobacco country, was home to the South's largest plantations and its highest concentration of slaves

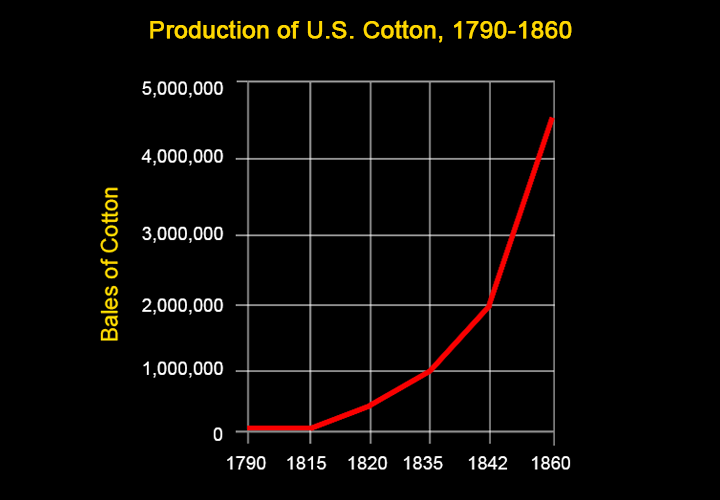

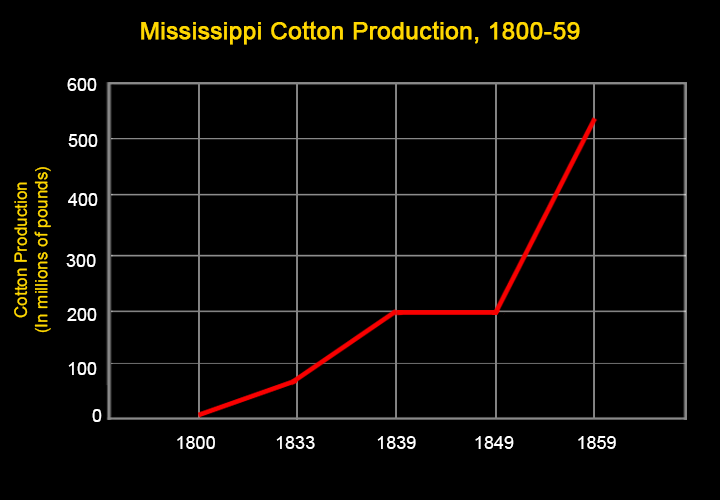

From a mere 3,135 bales produced in 1790, by 1815, the crop yielded 208,986 bales. Within 5 years, production had increased again by more than 50 percent to 334,378 bales. It reached the 1 million mark by 1835, and climbed to over 2 million bales by 1842. On the eve of the Civil War, the 1860 crop yielded 4 and a half million bales, more than doubling that of 1850.

- Growth of slavery

- Gadsden Purchase

- Francis Kemble

- Non-slaveholding Whites

- Increase of poor White population

- Southern social rank and slavery

- Slave ownership and number of slaves

Section Focus Question:

How did the southern expansion of the US fuel the cotton economy and the institution of slavery?

Key Terms:

The rise and expansion of the cotton kingdom that carried millions of Americans to the Southwest would have been inconceivable without the domestic slave trade. Slavery also benefited from US imperialistic ventures and wars of conquest, and fortuitous treaty concessions with European nations (the Louisiana Purchase most prominently), and not least, the conquest and resettlement of North American Native peoples.

The United States doubled its territorial size between 1790 and 1860. Lured by cheap land and the promises of riches, fleeing exhausted soil and the spiraling indebtedness that came with it, millions of Americans, joined by new immigrants from Europe, left for Ohio, Indiana, Nebraska, Arkansas, Alabama and Mississippi. Small and non-slaveholding farmers led the westward migration. While most did not become great planters, nevertheless, most did improve their economic standing. "A man who owned two slaves and nothing else," as historian Gavin Wright notes, "was as rich as the average man in the North."

The vast majority of white Southerners — nearly three-fourths — had no direct ownership of slaves or connection to slave ownership through family ties. Of the some 1.5 million free families in the South, only 385,00 owned slaves. Yet, even as slaveholdings and landholdings became more concentrated in the decades before the Civil War, small farmers, including those with no slaves, held their own in many ways.

Between 1850 and 1860, they increased their share of landholdings outside of the big plantation areas. The number of non-slaveholding small farmers increased from less than 40 percent to about 50 percent of all southern farmers. Conversely, the number of slaveholding families declined from 31 percent to 25 percent. Among small farmers, cotton growing, if not slaveholding, was significantly widespread.

Half of southern farms were worked without slaves but only one-quarter grew no cotton. Non-slaveholding white Southerners have often been viewed stereotypically as aimless, shiftless, and lazy. Francis Kemble called them "the most degraded race of human beings claiming an Anglo-Saxon origin that can be found on the face of the earth." This was generally hardly the case.

- Louisiana Purchase

- Thomas Jefferson

- William Lloyd Garrison

- Mississippi River Delta

- Cotton and territorial expansion

- "Habits of mutuality"

- Mississippi as a producer of cotton

- Slave migration to the Deep South

- Yeoman farmer

Section Focus Question:

How involved were Southerners in the slave economy of the South?

Key Terms:

Yeoman farmers represented the largest single group of Southerners. They were small landowning subsistence farmers who typically worked their own fields with the labor of their wives and children. Among them, a household economy predominated wherein yeoman families grew their own food and manufactured much of their own clothing, household furnishings, and farm implements. They typically devoted only a few acres to cash crops and grazed their stock on the commons and unenclosed lands, entering the marketplace to purchase what they could not produce.

As historian Steven Hahn writes, "common hunting and grazing rights took their place beside other 'habits of mutuality' — various forms of 'swap work,' for instance — as important features of productive organization." He notes, "Common rights, in short, not only enabled small landowners and the landless to own livestock, but they fit comfortably into a setting where social relations were mediated largely by ties of kinship and reciprocity rather than the marketplace." Yet, it is also clear that neither the way they lived their lives nor their relationship to the marketplace was immune to the dominance of the South's cash crop economy.

Cotton transformed the economy of the South and the lives of Southerners, black and white, male and female. More than sugar or rice or any other cash crop at the time, it fueled territorial expansion and westward migration. By 1860, some 1.6 million slaves and close to 3 million white people lived in the 6 southern states that had entered the Union between 1812 and 1845 — Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Missouri, Arkansas, and Texas.

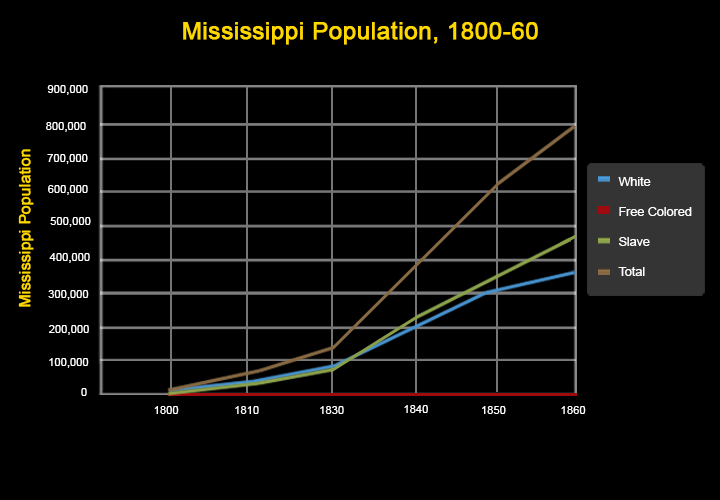

In Mississippi, which gained statehood in 1817, for example, the enslaved and the white population exceeded that of South Carolina by 1860. In 1800, Mississippi's white population stood at 5,179. In 1860, it was 353,901. The slave population of the state had jumped from 3,489 to 436,631 during the same period, representing 55 percent of the overall population in 1860. From virtually nothing in 1800, cotton production in the state grew correspondingly to 535.1 million pounds in 1859.

In the end, the massive wealth that the planters in the Southwest derived from cotton and sugar cultivation would not have been possible without the labor of enslaved men and women. They had been separated from family and dragged to the region and forced to labor long and hard to transform a wilderness into plantations and farms. They paid the highest price for southern economic dominance

The purchase of the Louisiana Territory, Thomas Jefferson wrote, provided "a wide-spread field for the blessings of freedom and equal laws." The "empire for liberty" that Jefferson envisioned was meant for white men and women. Between 1790 and 1860, an estimated 1 million slaves were transported to the Southwest, the vast majority between 1830 and 1860. The main exporting states — Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas — supplied over 85 percent. Most — some 75 percent — were destined for Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas.

But in 1831 with the publication of William Lloyd Garrison's famed abolition journal, The Liberator, the forces against slavery began to mount steadily and powerfully. At no point over the next 30 years did abolitionism secure the support of anything but a small proportion of white Northerners. Nevertheless, as John C. Calhoun among others quickly deduced, the danger to slavery was not insignificant. Those who "believed slavery to be a sin," Calhoun stated in 1837, "would consider it as an obligation of conscience to abolish it if they should feel themselves in any degree responsible for its continuance, and . . . this doctrine would necessarily lead to the belief of such responsibility" and ultimately disunion. "Abolition and the Union cannot coexist," he correctly prophesied.