Dilemmas

Note to students: The best preparation for taking the reading quiz is to pay close attention to the key terms as you read. Each question in the question banks is directly linked to these key terms and phrases.

Chapter Focus Question:

What dilemmas did the religious, middle class, and African Americans face in the North due to the political and economic developments?

- Second Great Awakening

- "Burnt-over district"

- Growth in Baptist and Methodist denominations

- Difference between Puritan faith and Second Great Awakening

- Conversion to abolitionism

- Blending of politics and Christianity

- "Perfectionist impulse"

- Charles Gradison Finney

- Rhetoric of freedom and liberty

Section Focus Question:

How did changes in political democracy and economic development affect the Second Great Awakening in the North?

Key Terms:

Economic development and political democracy can foster human liberation, but they can also cause dislocation. Old certainties give way. For example, should landownership be required to hold political office? Or, is it okay to pick your teeth at the dinner table? It is difficult to agree on new rules. It is also hard to put them in practice. Hierarchy and deference had structured society in many northern communities since the American Revolution. Thus, order might prevail in some places. This was true where a few controlled most of the property, controlled public offices, and held prominent lay positions in churches.

If social conservatives in these communities were to be believed, in previous times, workers obeyed their employers, congregants granted authority to their ministers, the poor respected their social betters, and wives listened to their husbands. But no more! "Our children hear so much about liberty and equality and are so often told how glorious it is to be 'born free and equal,'" lamented the president of Amherst College in 1840, "it is hard work to make them understand for what good reason their liberties are abridged in the family."

The demise of the traditional order owed much to a spirit of people wanting to think and do for themselves. But it also flowed from the physical migration of "strangers" to new cities such as Cincinnati, Detroit, Chicago, Pittsburgh, and Buffalo. The most extraordinary destination was New York City, where the population topped 200,000 in 1830 and 300,000 a mere decade later.

The North remained primarily rural, but the boisterous heterogeneity and blinding inequalities of urban places prompted fundamental questions for the society as a whole: Did a competitive market economy weaken or strengthen the moral obligations of people towards one another? Did the valuing of political equality promote excellence or mediocrity? What social conventions might tell people where they (and others) belonged in the absence of formal hierarchies? Northerners looked to practices of worship, demeanor, and diet, as they sought answers to these social questions.

Even as it regenerated community among strangers, faith did not always provide a refuge from politics. The "perfectionist" impulse turned temperance reformers into teetotalers. Colonizationists, who had previously favored buying slaves and returning them back to Africa, became abolitionists. Female congregants raised funds to promote missionary efforts in distant lands and nearby neighborhoods, and in so doing, they leveraged women's piety into public policy questions.

The North's religiosity reflected the broader culture's embrace of people's ability to choose for themselves, deciding among faiths as they would candidates and consumer goods. The logic of the marketplace seeped into the competition for dues-paying followers between established denominations, on one side, and their homegrown rivals such as Mormons, on the other. Significantly, evangelical Christianity's emphasis on adult conversion reinforced the premise that individuals controlled their own destinies — in the afterlife just as in the marketplace. Such tenets, however, also helped to justify class inequalities as divinely sanctioned and to provide cover for disciplining the impious.

- Penitentiaries

- Sylvester Graham

- Middle-class attitudes

- "Sphere of women"

- Middle-class morality

- Middle-class neighborhoods

Section Focus Question:

What are three features of middle class morality that changed American social life by mid 19th century?

Key Terms:

Northerners with the economic means to do so sought refuge from the marketplace in the sanctity of the home. If an emerging middle class had any overarching agenda, it was to enforce a strict boundary between the affective relations of domestic life and the dog-eat-dog world outside. As conveyed in popular periodicals, the public and private should constitute "separate spheres." Male breadwinners ventured into the polluted marketplace and women protected the home from it. This was easier said than done, considering the consumerism associated with middle-class refinement and the paid servants who perform labor that "ladies" wouldn't.

Prosperous families had once resided adjacent to poorer families in the urban core of cities. But the middle class now clustered in homogenous neighborhoods remote from the clamor of the waterfront, the stink of the tannery, and the impositions of beggars. A new domestic architecture further demarcated private and public space. The ideal home featured a front parlor to entertain visitors on fancy (if uncomfortable) furniture, and a back parlor was reserved for intimate family activities such as practicing the harpsichord and reading novels. New models of gender discouraged authoritarian husbands, stressed love as the foundation of companionate marriages, and sentimentalized death.

Rather than placing young children in apprenticeships or relying upon their household labor, middle-class families understood childhood as a distinctive developmental phase requiring maternal nurturing until adulthood. Domestic power offered women an unprecedented role in society, observed Catharine Beecher, who touted women's greater morality, piety, and selflessness. At the same time, this model of "true womanhood" provided a rationale for disfranchising women and denying them educational access in the name of protecting them from corruption. Moreover, it impugned and questioned the femininity of women who labored outside the home, lived in non-nuclear households, or lacked the resources to devote to their children's education.

Access to the middle class was less about income than about attitude: an ethos of delayed gratification, an aspiration to improvement, and a belief in meritocracy. Most important were the practices of self-discipline that moderated appetites, restrained sexuality, and brought the veil of privacy over bodily functions. Health reformers like Sylvester Graham advocated vegetarianism and prescribed a steady diet of crackers to assist young men in battling the "solitary vice," referring to masturbation. Etiquette guides taught the rules of respectability and allowed table manners, posture, and conversational gestures to become proxies and demonstrations for moral rightness.

Participation in reform movements also signaled one's middle-class status, especially "benevolence" dedicated to instilling middle-class values in the poor. New York's House of Refuge, founded by the Society for the Reformation of Juvenile Delinquents, institutionalized rowdy street urchins until they came to appreciate the virtues of hard work and thrift. A growing network of penitentiaries operated on a similar logic, replacing whippings and hangings with lengthy terms of incarceration.

Compulsory public education, owing to the work of Horace Mann in Massachusetts, became the primary vehicle for socializing the next generation. Public schools could open opportunities for upward mobility and help assimilate immigrants. Critics, however, feared they mostly disciplined children into reliable factory laborers. In sum, the greatest success of the middle class was in making its particular value system appear to be universal, natural, and the logical extension of the republicanism that had previously defined American political culture.

- White supremacy and the Irish

- Race mobs in Providence

- Wages of Whiteness

- White Northerners' disrespect for African Americans

- Reform vs. discrimination

- Working class comparison to slavery

- Black citizens in New York

Section Focus Question:

How did racism manifest itself in the North?

Key Terms:

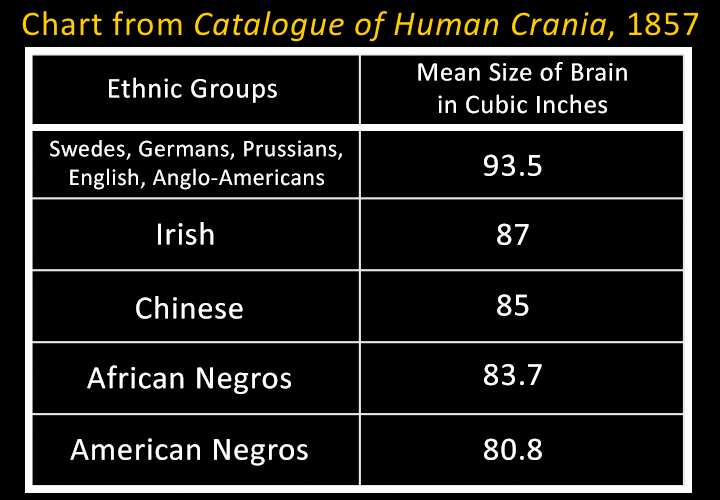

Northern society struck observers as remarkably fluid in all ways but one: its investment in racial hierarchy. The freedom that African Americans had attained over several generations did not bring forth equality. Without slavery to demarcate racial boundaries, Northerners seemed to work twice as hard to invest white skin with social power. Natural historians like Samuel Morton and Louis Agassiz provided racism with scholarly credentials by measuring skulls and equating ancestry with essential biological difference.

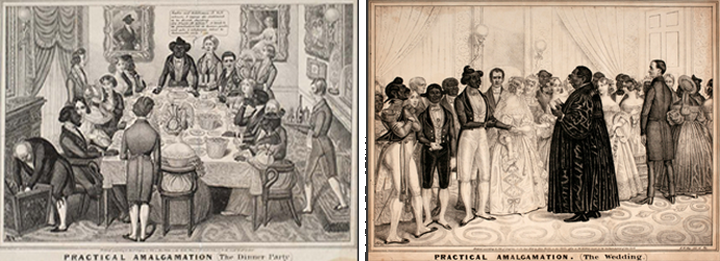

Popular culture denigrated African Americans, as white minstrels performed in blackface and satirical prints posed racial intermarriage as the inevitable outcome of antislavery agitation. Mockery readily gave way to violence as white rioters targeted black-owned property in cities like Providence. Embracing the norms of white supremacy provided a pathway to assimilation for Irish immigrants, assured by the Democratic Party that all white men were equal in their superiority to blacks. Working-class men found little security on the job, but took compensation in the "wages of whiteness" and the social privileges of not being black.

"The North" became a coherent cultural entity by comparing itself to the slaveholding South. Abolitionist propaganda couldn't sway the broader population in favor of immediate emancipation. Nevertheless, it publicized patterns of sexual abuse and domestic violence that confirmed Northerners in their idealization of the nuclear family. In turn, middle-class notions of the home as a sanctuary from the market provided the basis for criticizing slavery's transformation of parents and children into commodities.

Northerners who might be agnostic or ambivalent on the question of slave-owning bristled at slave-selling and the family separations that followed. In a similar way, slavery set the terms of labor conflict in the North, whether in workers' cry of "white slavery" or employers' dismissive retort that slaves didn't get to keep their wages.

The presence of actual slaves within the same nation ultimately served to make inequality more tolerable in the North than it might have otherwise been. We shouldn't discount the process by which a sizable percentage of the North came to see slavery as a moral problem. But we must also recognize that the more slavery appeared uniquely wrong, the more anything that wasn't slavery could be construed and perceived as freedom.

Whereas earlier generations had based freedom on propertied independence, the bar would soon be lowered to simply someone who wasn't a slave. In effect, the self-owned individual was entitled to familial integrity, a vote, and the right to compete in the marketplace. Equality of opportunity, not equality of condition, assumed primacy in the social contract. This version of freedom — one that emerged haltingly in response to the specific tensions of development and democracy — would come to seem inevitable in the wake of the Civil War and timeless as it carries into the present day.