Filling Up the Canvas of America: The West

Chapter Focus Question:

How did the exploration and acquisition of western lands challenge American identity?

- Fort Mandan

- Few casualties in the expedition

- Comte de Buffon

- Fort Clatsop

- Water passage and commerce

- Natural history museum in Philadelphia

- Lewis and Clark expedition under Indian attack

- Sacajawea

- Lewis and Clark expedition goals

- Three major expeditions and time frames

- Expedition objects in Jefferson's home

- Lewis and Clark expedition outcomes

- Charles Wilson Peale

- Mastodon

- Lewis and Clark and proclamation of sovereignty

- Pike expedition and the Southwest

- Lewis and Clark expedition at Cape Disappointment

Section Focus Question:

What were the goals Jefferson set for the Lewis and Clark Expedition, and what did it accomplish?

Key Terms:

The acquisition of western lands presented Americans with opportunities to imagine the future of their republic as a great “empire of liberty.”

With the birth of the new nation came a series of exploratory expeditions that added greatly to American and European knowledge of North American geography, Native peoples, and nature. Much of this new knowledge concerned the land west of the Appalachians, the mountain range that had long stood as a major barrier to extensive western American settlement. By the end of the Early National Period, Americans had created maps of the whole of the American continent, stretching all the way to the Pacific Ocean. These maps were far more detailed and accurate than any produced to date.

Today we take it for granted that Americans knew about the whole of the American continent. But in the first decades of nationhood, much remained unknown and even shrouded in mythology. Was there, as some early maps suggested, a Great River of the West that would allow a water passage between the Atlantic and Pacific so that ships did not have to travel around the tip of South America or seek the elusive, icy Northwest Passage north of Canada?

Americans also wondered about the Native peoples who lived further west: how many were there, and could they become trading partners with Americans rather than the Spanish Empire, which still laid claim to much of the western North American continent? Finally, in an era that had not yet developed the idea of species extinction, Americans hoped to find living examples of the elephant-like mastodons, whose huge fossil bones they had unearthed in New York and Ohio. They wanted to show Europeans that American animals, plants, and people did not become smaller, weaker, and less fertile in the New World, as some influential European thinkers such as the Comte de Buffon had argued.

President Thomas Jefferson, who had a great interest in geography and nature, expressed Americans’ sense of exciting possibility about this new era. We shall delineate with correctness the great arteries of this great country: those who come after us will…fill up the canvas we begin.

The canvas began to be filled by what eventually became the most famous of these journeys: the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804-06. Headed by Captain Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, the roughly 45-man “Corps of Discovery” headed up the Missouri from St. Charles (near St. Louis) in small boats to gather knowledge about the newly acquired territory of the Louisiana Purchase.

President Jefferson had many goals for the trip, including establishing US sovereignty over the Native Americans along the Missouri River. He especially hoped to find an overland route to commerce with Asia, as he explained in his instructions to Captain Lewis: The object of your mission is to explore the Missouri River, and such principal streams of it, as, by its course and communication with the waters of the Pacific Ocean, whether the Columbia, Oregon, Colorado, or any other river, may offer the most direct and practicable water communication across the continent for the purposes of commerce.

Many things are remarkable about the Lewis and Clark Expedition, not the least of which is that only one person died (of appendicitis), despite such terrifying events as charging grizzly bears. The expedition spent the long winter of 1804-05 among the Mandan Indians of present-day North Dakota, where they were joined by a Shoshone woman, Sacagawea, who helped translate for the expedition as it continued westward in the spring. They reached the Pacific Ocean in fall of 1805 and soon began the long journey back east. Throughout the expedition, Lewis and Clark kept detailed journals, even sketching the animals and plants they saw. These journals were published in various forms over the years, adding greatly to Americans’ understanding of the western regions of the continent.

Lewis and Clark also sent natural specimens back to the East Coast, including animals, birds, insects, plants, and artifacts from the Native American groups they met. Over 200 new animals and plants—as yet unknown to American science though already known to Native peoples—emerged from the expedition. Some went on display in America’s first natural history museum in Philadelphia, founded by the artist and naturalist Charles Willson Peale. Peale’s self-portrait, made in 1822, shows him lifting a red curtain to reveal some of the specimens sent back from the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Many of the most beautiful Indian objects, such as a Mandan buffalo robe depicting war scenes, ended up in Thomas Jefferson’s home, Monticello, where he displayed them for his many visitors to see. One of the greatest achievements of the Lewis and Clark Expedition was an extraordinarily detailed map of western America, published in 1814. The map gave citizens of the United States an utterly new vision of the territory west of the Mississippi River. In addition to giving population figures for many Native American settlements (counted in “souls”), the map supplied the most accurate depiction to date of the sources of the Missouri River and the topography of the Rocky Mountains. The sheer height and immensity of this mountain range shocked many expedition members, whose only experience with mountains had been the relatively low Appalachians.

- Purpose of Pike's expedition

- Pike's expedition results

- Pike's expedition events

- Pike's peak

Section Focus Question:

What were the goals of the Pike Long expedition, and what was its legacy in American history?

Key Terms:

As the Lewis and Clark Expedition wound down, the US government dispatched a second westward expedition under the command of US Army Lieutenant Zebulon Pike. The Pike Expedition explored the territory of what is today Colorado in 1806-07. (Pikes Peak in Colorado is named for him.) This expedition reveals the important role that Native Americans and the Spanish Empire continued to play in the early national period. Some of the territory explored by the Pike Expedition had only recently been wrested by the US from the Spanish Empire, which still claimed most of what we today would call the American Southwest, from present-day California to Texas and New Mexico. Pike’s mission, in part, was to inform the Native Americans inhabiting the region that the United States now claimed authority there.

Pike and other members of this expedition were captured by the Spanish, who complained to the US government that this was a military rather than scientific expedition. The captives were soon released, since they were citizens of a nation not at war with Spain. While a captive, Pike took the opportunity to gather information about the area that is now New Mexico and Texas. When Pike returned to US territory, he published an account of his expedition and a detailed map of the Southwest, a region still under the control of the Spanish Empire and powerful native groups. Pike’s map showed the location of key Spanish towns and forts, as well as Native American trails and villages. This information would be put to use during the next few decades, as Spain and then Mexico continued to play a large role in American foreign and domestic policy.

- Long expedition and steamboats

- Impressions of the West from Long's expedition

- American system

Section Focus Question:

What were the goals of the Long expedition, and what was its legacy in American history?

Key Terms:

The third major expedition, headed by US Army Major Stephen Long, capped the exploratory achievements of the early national period. The Long expedition marked the beginning of a series of “firsts,” including being the first American expedition to move primarily by steamboat. It was also the first to yield a veritable flood of beautiful images of the west—many drawn on site—at the very dawn of the great age of American landscape painting.

President James Monroe dispatched Long and a cadre of around 20 men in 1819-20 to explore the central and southern Great Plains and the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains, the very northwest border of Spain’s empire in America. Showing the growing importance of science in American life, this was the first expedition to incorporate a cadre of trained naturalists, including Thomas Say, America’s foremost insect and shell specialist. Skilled artists also joined the Long Expedition, including the nature painter Titian Peale and the landscape painter Samuel Seymour.

The results of the Long Expedition reflect one of the developing paradoxes of the American West. As it became better known through maps and surveys, the West became a place for the development of new—and conflicting—national mythologies. For some, the West was a place of untrammeled natural beauty; for others, it was a savage, frightening, and “wild” place. Some of the images produced by the Long expedition are evidence of the development of the first ideal.

The artists and scientists accompanying Stephen Long produced a memorable series of images of mountains, plants, and animals. Thomas Say published the first book in the world dedicated solely to American insects. Titian Peale made over 100 sketches of the Native Americans, birds, and shells of the region, including a haunting image of an Indian buffalo hunt. Samuel Seymour’s landscape painting, Distant View of the Rocky Mountains, stands at the beginning of the 19th-century tradition of American landscape painting, which depicted the West as the site of God’s greatest, most majestic natural creations.

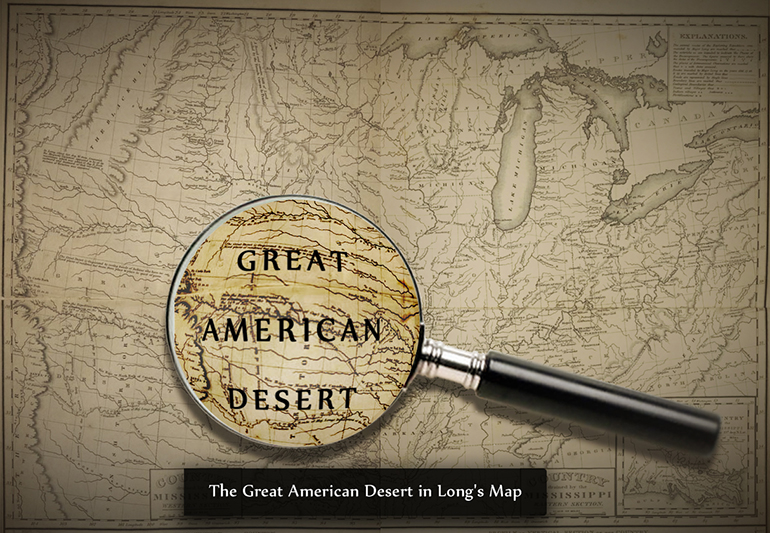

But the West also seemed frightening: a forerunner of the savage “Wild” West. Long’s map, which draped the phrase, “GREAT AMERICAN DESERT” over the region east of the Rockies, suggested a wild, unforgiving land. Expedition geographer Edwin James bewailed this land of few trees and little water, unsuitable for the virtuous nation of farmers envisioned by Jefferson. I do not hesitate in giving the opinion, that it is almost wholly unfit for cultivation, and of course, uninhabitable by a people depending upon agriculture for their subsistence.

What, then, would the West be? More broadly, what would the US be? The end of the early national period left Americans with more questions than answers about their national destiny. The conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 brought a national mood of exaltation that the young republic had survived to the quarter-century mark in defiance of all European expectations. Political strife diminished, and an aggressive new “American System” of internal improvements, such as canal and road building, was launched. The new sense of peace, power, and purpose that came with the opening of the administration of James Monroe is often termed the “Era of Good Feelings.”

Others, however, sounded a pessimistic note. Thomas Cole’s Course of Empire series, five paintings the artist completed in the 1830s, sounded a somber note about the American future. Moving through an imaginary series of Rome-like views from a primitive age of savagery to a gilded, bustling city, and then to a cataclysmic failure, Cole’s Course of Empire series warned Americans that territorial expansion, commercial development, and urbanization might be harbingers of doom, condemning the US to fall just as Rome had done a millennium and a half before. The final painting of Cole’s series left America’s national destiny as a great question mark. Ruined columns stand quietly in a moonlit swamp: would the American republic also end in desolation? And what could Americans do to prevent America from sharing the fate of Rome?