"What then is the American, this new man?"

Chapter Focus Question:

How did Americans establish their national identity through territorial expansion and political debates?

- Parson Weem's myth about George Washington

- King George III

- Early National Period challenges

- National identity in the Early National Period

- Early National Period features

- Tecumseh

Section Focus Question:

What actions did Americans take to establish a national identity?

Key Terms:

Internal disputes and questions about what it meant to be a citizen in a republic characterized the early national period.

Among the first tasks awaiting Americans in the period 1790-1815 was simply defining what it meant to be American. "What then is the American, this new man?" asked Hector St. Jean de Crèvecoeur at the end of the American Revolution. Crèvecoeur had emigrated from France to America, as an observer from a monarchical society. He was especially interested in how the particular conditions of America shaped the society, politics, and people who lived there. Today we take the existence of an American identity for granted, but Crèvecoeur's question shows that this identity had to be invented. Until just before the American Revolution, many Americans would have identified themselves as members of the British Empire, a status that they thought gave them many liberties and privileges. But suddenly in 1776, as they declared political independence from Britain, the former colonists and subjects of King George III had to become the citizens of the United States of America.

Americans found many creative ways to forge this new national identity in the period 1790-1815. Sometimes they simply invented new names for things. King's College (named for Britain's King George II) became Columbia University, in honor of the invented republican goddess and symbol of the US, Columbia. But a lot of the work was long and hard. From the ground up. Americans who had relied on existing structures within the British Empire during the colonial period now had to develop new institutions.

They had to create an army, a navy, new universities, law schools, medical schools, and museums, and to forge new trade relationships with other nations. The separation of powers mandated by the Constitution led to the development of the idea of judicial review of legislative and executive actions, as in the case of Marbury vs. Madison (1803). Americans now created their first national myths. It was in the early 1800s that an obscure minister known as Parson Weems invented the myth of George Washington and the cherry tree.

Finally, because so few examples of successful republics existed in the modern period, Americans turned instead to the classical past to ensure that their own republic avoided the tragic end of the Greek city-states (which were eventually conquered by Rome) and the Roman Empire (which eventually fell to barbarian attack in 476 CE). "Let us take warning from their errours and misfortunes," urged the governor of Massachusetts in the early 1800s, "and may Heaven preserve us from a similar destiny."

In every aspect of life – politics, art, education, architecture, and even clothing and interior decoration – Americans of the early national period used examples from Rome and Greece, a movement called "neoclassicism." Neoclassicism is still visible today in the architecture of the federal city, Washington, DC, which was designed and built beginning in the 1790s.

- Population growth doubling every 25 years

- Relationship between international and national slave trade

- International slave trade ends in 1808

- Internal slave migration

- Free Blacks

- Louisiana Purchase

- Neoclassicism

- Relationship between cotton and slavery

- Indians in the US Constitution

Section Focus Question:

How territorial expansions affect the Native Americans and the slaves?

Key Terms:

The early national period opened an era of rapid territorial and population growth. The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 essentially doubled the size of the United States overnight, extending US land claims beyond the Appalachian Mountains that had long formed an informal western boundary of British-American settlement. To the existing 13 states another five were added by 1815, all but one in the land west of the Appalachian Mountains.

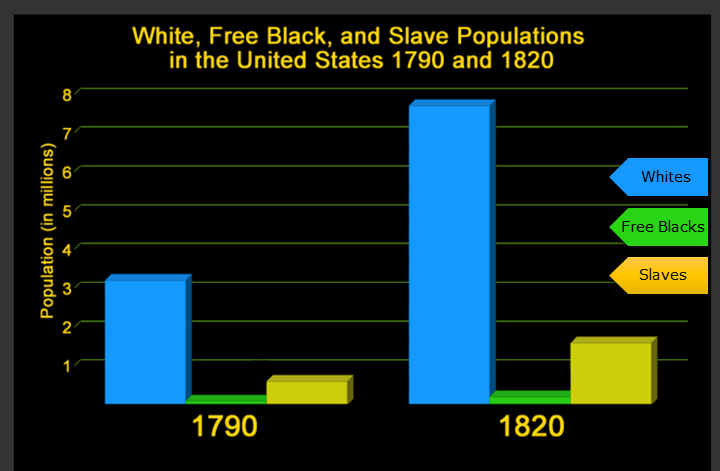

In the three decades between 1790 (the year of the first federal census) and 1820, the US population grew from around four million to almost 10 million, a faster rate of increase than ever before. This rapid population growth seemed to confirm Benjamin Franklin's famous observation that plentiful land and cheap labor in North America would cause its population to double every 25 years.

Population growth told only part of the story of the new American republic. First, Native Americans living on reservations and in tribes within US territory were not counted in the federal census at that time. They appear in Article I of the US Constitution as "Indians not taxed" and therefore not counted for purposes of representation.

Yet the numerous Native peoples of North America continued to have a major impact on the development of the United States and on the activities of other European powers in North America, such as Britain and Spain. The War of 1812 dealt a decisive blow to the Native Americans who had allied with the British against the US, a defeat symbolized by the death of the great leader Tecumseh in 1813. The next century would see the precipitous decline of Indian populations in North America and their displacement onto reservations.

The early national period also saw the rapid growth of slavery in the United States. Slavery had existed in British America since the 17th century, but now the number of slaves grew far more rapidly than before. In 1790 there were roughly 900,000 slaves within the United States; by 1815 that population had increased to about 1.5 million. On the eve of the American Civil War in 1861 most of the roughly four million slaves of the US lived in the South.

The domestic and global demand for American cotton explained some of this growth; American planters gradually moved into the new southwestern territories that became the states of Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana, a region that became known as the "Cotton Kingdom." Because the US Constitution had ended the importation of slaves by 1808, an internal slave trade developed and slaves were transported from the older eastern slave states of Virginia and the Carolinas into the new Cotton Kingdom.

- First two Federalist presidents

- American newspapers

- James Madison and the virtues of a large republic

- Federalist positions

- Early American culture

- First Party System

- Alexander Hamilton vs. Aaron Burr

- Empire for Liberty

Section Focus Question:

How did the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans differ in their policies for the new American Republic and how did these issues demonstrate the growing tensions among the new nation?

Key Terms:

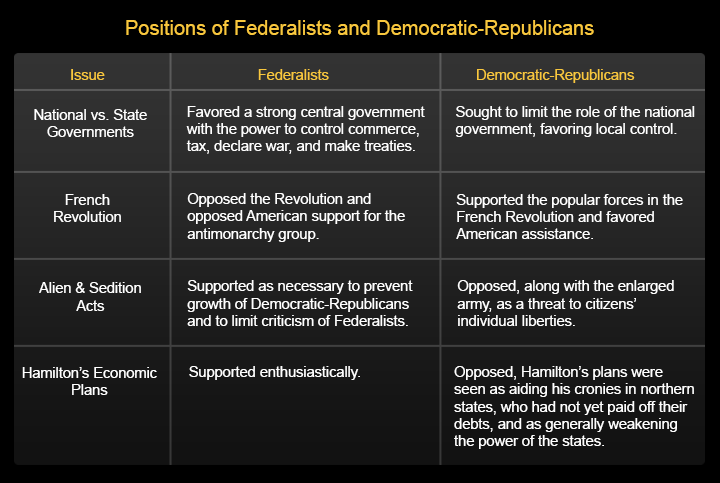

Political problems threatened to derail the new nation. With the American Revolution now behind them, the nation's leaders began to articulate different visions of how the republic should develop. Some subscribed to the ideas of Alexander Hamilton, the first secretary of the US treasury. In his Report on Manufactures (1791) and elsewhere, Hamilton championed a strong, centralized state, with industry supported by subsidies and tariffs. In one form or another, this cluster of ideas found many followers among a new group called Federalists, including the first two US presidents, George Washington and John Adams. (This group should be distinguished from the earlier Federalists, the name given to those who supported the ratification of the US Constitution.)

Others believed that the US should remain a decentralized agricultural nation, with few manufactures. Jefferson's purchase of the enormous Louisiana territory in 1803 would help to create what he called an "empire for liberty," an ever-growing republic held together not by tyranny or force of arms but by ties of common interest and affection. Implicit in this vision of the United States was a large role for slavery, and it is no surprise that it gained the most supporters in the South and Southwest.

In this vision of America, the common people (defined as white men) would govern based on their own merit rather than on inherited status or wealth. This set of beliefs was most effectively expressed by the Virginians, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, both slaveholders, who were presidents during the period 1801 to 1817. "Those who labour in the earth are the chosen people of God," wrote Jefferson in his Notes on the State of Virginia (1785), a phrase that is today inscribed in the Library of Congress.

In essay 10 of The Federalist (1787-88), Madison had influentially proposed the new idea that a republic should be large, so as to prevent the formation of majority factions. This view – which contradicted the ancient idea that republics could only be small, so that their people would be united in their opinions – effectively authorized limitless American territorial expansion. Those who supported these ideas clustered in the party that became known as the Democratic-Republicans. Together, the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans formed the first US party system, which remained in place until it was displaced by the second party system in the mid-1820s.

These political disagreements surprised the Americans who had formed more or less common cause against Britain during the Revolution. Political parties were a new idea at the time, and many Americans took them as an ominous sign that the republic would soon fracture into squabbling factions that would make the US prey to foreign attack.

Disagreements between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans took many forms during this era. Some were highly personal, such as the deadly duel that took the life of Alexander Hamilton, fatally shot in 1804 by the Democratic-Republican Aaron Burr, Jefferson's vice-president. Other conflicts revealed growing regional schisms. At the Hartford Convention of 1814, New England Federalists threatened to secede from the Union, believing that their vision of the United States was threatened by Democratic-Republicans and the growing power of the western and southern slave-holding regions.