The Patriots: "Survive or Perish with My Country"

Note to students: The best preparation for taking the reading quiz is to pay close attention to the key terms as you read. Each question in the question banks is directly linked to these key terms and phrases.

Chapter Focus Question:

What were the factors that led to the Colonists declaring independence from Britain, and how did public opinion for and against the war factor into the success of the war?

- British Constitution

- British abuse of the Irish

- British/colonial disputes

- US Constitution

- Revolutionary government structure

- American wealth

- Opposition centered in Boston

- American opinion

- Democracy as a negative word

- Voting and property

- No taxation without representation

- Boston Tea Party

Section Focus Question:

What were the similarities and differences between the structure of the British mixed government and the American Colonial government, and why did the British mixed constitution not work effectively in the colonies?

Key Terms:

In the 1770s tensions between the colonists and the British increased. Some Americans, known as the Patriots, became disillusioned with British rule and began to push for the establishment of an independent republic, while others, known as the Loyalists, preferred to keep the colonies under the rule of the British Crown.

The colonists had grown up hearing and believing that the British constitution was the finest in the world. Unlike the later American federal constitution, the British constitution was not a written document but instead a consensus understanding of the political institutions of the realm. According to prevailing political thinking, Britons enjoyed an ideal mixed constitution which preserved a balance between the three elements in any proper society: the one (the monarch), the few (the aristocrats), and the many (the common people). The monarch (usually a king, sometimes an unmarried queen) led the executive branch while the British had a bipartite legislature: the House of Lords for the few and the House of Commons to represent the common many (but only those with enough property to qualify to vote).

Political thinkers regarded a mixed constitution as better than a tyranny (the rule of one man), an oligarchy (the rule of the few), or a democracy (the rule of the many). A tyrant or oligarchy would rule the common people with an iron fist, while a democracy would lead to anarchy. At that time, educated people regarded democracy as a negative word. They feared that unscrupulous politicians known as "demagogues" would grab power and encourage the poor majority to plunder the rich minority.

According to political theory, only a mixed constitution could provide the proper checks and balances to preserve stability. The king, aristocracy, and commons would have to cooperate in Britain's mixed constitution to produce the common good while preserving the right degree of liberty for everyone. This was the conventional political wisdom believed in the colonies as well as in Britain before the American Revolution. Such a mixed constitution made sense in an empire where people were not equal in their property, civil rights, or political influence.

The colonial governments were supposed to operate as subordinate versions of the British constitution with a royal governor, appointed by the king, to represent the monarch, and with an elected assembly modeled on the House of Commons. The third institution was a council comprised of men nominated by the local assembly and approved by the royal governor. Every colony, even tiny Rhode Island, had its own government and there was no coordinating body within the colonies to unite them.

The colonies deviated from British society in two ways that kept the colonial governments from functioning according to proper political theory. First, when compared to the electorate for Parliament, in America many more men qualified to vote for representatives to the colonial assemblies. Only free men could vote in the colonies and Britain, and the same property requirement prevailed on both sides of the Atlantic: a man had to own enough property to support himself and his family in order to vote. To meet the requirement, a man needed his own farm or shop. Women had no political rights, even if they owned property as widows.

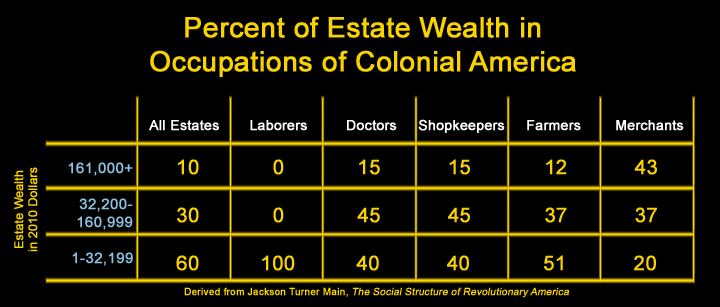

Only a quarter of English men owned enough to vote, but at least half and perhaps two-thirds of the free men in America had political rights. The difference derived from the relatively thin population in the colonies, which meant that more common men owned farms and, therefore, could vote. As a consequence, the American colonial assemblies had a more popular and democratic style than did the British Parliament.

In a second key difference, the colonies lacked the true aristocrats to render the councils truly equivalent to the British House of Lords. In the colonies, there were no lords, dukes, earls, and marquises to inherit titles and large, landed estates worked by tenants. The colonies had plenty of rich men, but they were planters, lawyers, and merchants who relied on buying and selling property to make and keep their money. The wealthiest colonists relied on commerce rather than inheritance for their fortunes.

Members of the councils were thus richer versions of the merchants, lawyers, and planters who served in the assemblies. In political disputes, the councils usually sided with the assemblies against the royal governor. As a consequence, British officials regarded the colonial governments as out of balance. Britons considered the colonial governments too republican, because the governor and the council did not cooperate to restrain the too powerful and too popular legislatures of the colonies. Prior to the revolution, republican was a bad term that, like democracy, connoted instability and anarchy.

During the mid-1760s Parliament and the Crown officials regarded the colonists as distant and wayward inferiors who had to be restrained and taxed for the greater good of the empire. The colonists, however, wanted to return to the looser empire of the early 18th century, for that empire provided great trade benefits at minimal cost in taxes. Proud of their British heritage of civil liberties, the colonists insisted that the Empire's rules and their taxes could not be changed without their consent expressed through their elected representatives. Adopting the slogan "No Taxation without Representation" they resisted the new measures adopted by Parliament. The colonists did not seek seats in Parliament. Instead, the colonists insisted that only their own elected assemblies could legally tax them.

The colonists regarded the new taxes as a threat to their liberty, which they tied to their property rights. Elected in Scotland, England, and Wales, the Members of Parliament preferred to shift the tax burden off of their own constituents and onto the colonists. The outraged colonists drew a grim picture of future taxes piling up until the farmers and artisans would have to sell almost all of their property to pay them. Once without property, they would lose their political rights. And people with neither property nor rights suffered greatly in any empire.

Colonial protestors pointed to the plight of Irish peasants living under British rule. Although a majority of Ireland's people, peasants had no political rights and suffered heavy taxes and rents as tenant farmers. The British exploited the Irish to benefit a landlord class and the merchants of the mother country. In North America the colonists dreaded the same fate if they submitted to the taxes levied by Parliament. Although initially small, the taxes set a precedent that could lead to more and heavier levies down the road. Indeed, many colonists began to suspect a conspiracy against their liberty and prosperity by a cabal of British officials. There was no such conscious plot, but many colonists believed that there was, so they acted on that belief.

During the 1760s colonists opposed the new taxes, but they did not yet seek independence. The colonists benefited from the protection offered by the powerful Royal Navy against the French, Spanish, and pirates. The colonists also profited by trading with the many ports of the vast British Empire, the largest market in the world. Instead of seeking independence, the colonists wanted to revert to the good old days of protection and prosperity without imperial taxes. They wanted the benefits of the empire, without paying its heavy costs. They justified that privileged position by citing the profits that British merchants and manufacturers made by selling to the growing American market.

- American resistance to British taxes

- Opposition to taxation

- American opinion before the revolution

Section Focus Question:

Colonists used 3 forms of resistance to protest British taxation: intellectual protest, economic boycotts, and violent intimidation. How were these methods of protest successful, and how did the British government respond?

Key Terms:

Resistance to the new taxes took three forms: intellectual protest, economic boycotts, and violent intimidation. First, the political leaders of the colonies wrote pamphlets and adopted resolves to make a legal and intellectual case against the new taxes. Second, the protest leaders sought to unite the colonists, particularly the merchants, to boycott British goods. By refusing to import or sell British products, the protesters hoped to inflict so much economic pain on the mother country that Parliament would back down and rescind the taxes. Third, large, angry crowds enforced the boycotts and resisted tax collection by bullying any American who broke ranks. It became dangerous to try to collect the taxes or even to speak up in support of Parliament's right to levy those taxes. Suspected violators of the boycott could also suffer beatings or some destruction of their property: windows smashed, fences toppled, and livestock mutilated.

The three forms of resistance worked together. The boycotts required a common front, which intimidation of wayward people helped to produce. And the colonial leaders produced arguments that cast the boycotters and bullyboys as defenders of colonial liberty against a plot by British tyrants.

Although few and small, the colonial cities hosted most of the resistance in all three forms. Most colonists lived on farms or plantations in the countryside. Only about five percent dwelled in the cities, all of them seaports dedicated to importing British manufactures and exporting colonial agricultural produce. On the mainland of North America, the four leading cities were Boston (in Massachusetts), New York City (New York), Philadelphia (Pennsylvania), and Charleston (South Carolina). Only Philadelphia topped 30,000 inhabitants. In the seaports taxes were opposed, boycotts enforced, and arguments framed for the resistance.

In 1765 the combination effectively frustrated the Stamp Tax levied on almost every paper document in the colonies including newspapers and playing cards. Mobs damaged the homes of imperial officials and their colonial supporters. A boycott hurt British manufacturers and exporters. Delegates from nine of the colonies gathered in New York to draw up resolutions denouncing the taxes and coordinating the resistance. In 1766 Parliament grudgingly repealed the Stamp Tax.

But Parliament kept trying other, more indirect taxes on trade goods in the vain hope that the colonists would agree to pay them. In every case, the colonists resisted, which frustrated imperial officials and the Members of Parliament. They became especially angry in late 1773 when Bostonians disguised as Indians boarded ships to smash and dump a cargo of tea into the harbor to prevent anyone from buying the tea and so paying the tax levied on it. This was the famous Boston Tea Party. One Member of Parliament denounced Boston: "I am of the opinion [that] you will never meet with that proper obedience to the laws of this country until you have destroyed that nest of locusts."

In early 1774 Parliament adopted a set of Coercive Acts meant to punish the town of Boston and the colony of Massachusetts. Parliament shut down the port, banning all trade until the residents paid for the destroyed tea including the tax. To enforce the shutdown, the Crown sent warships to command the harbor and troops to occupy Boston. Parliament also restructured the colonial government of Massachusetts to make it conform more closely to the British model of a mixed constitution. The royal governor gained the sole power to appoint (or discharge) the members of the council. The British wanted to swing the council away from control by the popularly elected assembly.

The Coercive Acts escalated the confrontation in Massachusetts. Once confined to Boston, the resistance spread into the countryside as hundreds of men and boys, armed with guns and clubs, gathered to shut down the courts of law. They also bullied anyone who supported enforcement of the Coercive Acts. The violence scandalized those people who preferred strict law and order and obedience to Parliament. If they spoke out, mobs vandalized their houses and covered their bodies with hot tar and feathers.

Calling themselves Patriots, the leaders of the resistance in Massachusetts looked to the other colonies for support. Would they regard the Coercive Acts as their problem as well? Although sure that the Bostonians had gone too far with their violent tea party, most colonial leaders also felt that the British had overreacted. Throughout the colonies, Patriots dreaded that the Coercive Acts set precedents that would soon be applied to all the colonies. After the Coercive Acts, more colonists suspected a British plot to impoverish and dominate them.

- First Continental Congress

- American opinion

- Concord

- Lexington

- Thomas Paine

- Losers in the American Revolution

- Revolutionary documents

- American opinion

Section Focus Question:

The Continental Congress encouraged the formation of revolutionary governments and took responsibility for fighting the British. How did Loyalists and Patriots respond to the formation of revolutionary governments and the war?

Key Terms:

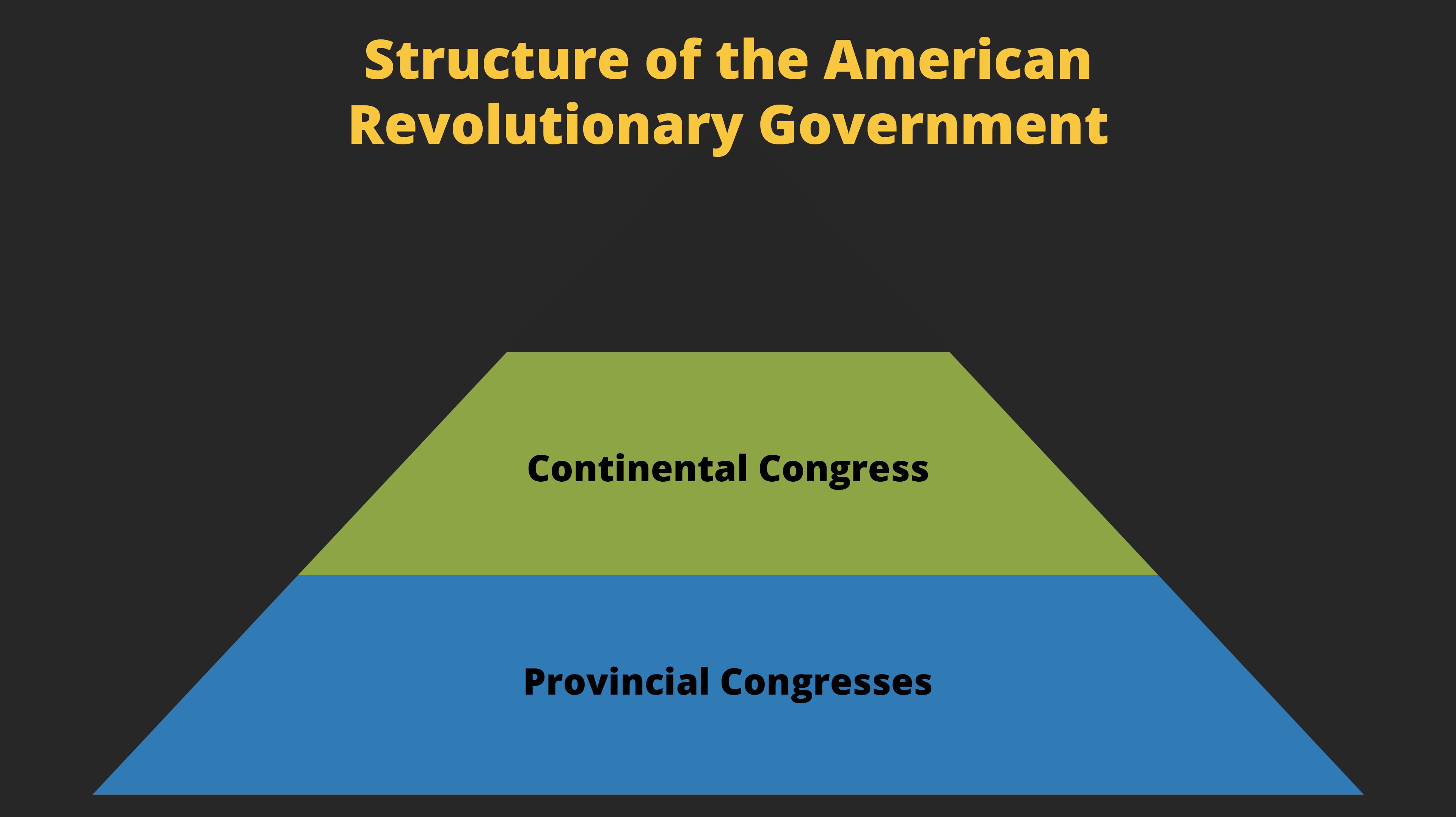

Delegates from 11 of the colonies met in Philadelphia in the fall of 1774 and voted to support Massachusetts. They agreed to impose a new trade boycott until Parliament withdrew the Coercive Acts and the troops occupying Boston. This First Continental Congress encouraged counties and towns to set up local committees to enforce the boycott and intimidate those who supported British policy. The emerging web of committees answered to new provincial congresses that emerged in every colony, and all looked for guidance to the Continental Congress. The Patriots had created a parallel set of political institutions to defy the regular colonial governments. Still wary of full independence, the Patriots promised to dissolve their extralegal, parallel governments if Parliament backed down.

The escalation of the constitutional crisis divided the colonists. Most supported the boycott, the new committees, and Congress. But a large minority feared continued resistance to Britain as illegal and dangerous. These Loyalists considered the mobs and committees as far worse than British rule and taxes. One Loyal American declared, "If we must be enslaved let it be by a king at least, and not by a parcel of upstart lawless committeemen. If I must be devoured, let me be devoured by the jaws of a lion, and not gnawed to death by rats and vermin." Another asked, "Which is better to be ruled by one tyrant three thousand miles away or by three thousand tyrants less than a mile away?" Loyalists feared anarchy by their neighbors more than domination by the distant king and Parliament.

Loyalists also felt that further resistance to Britain would lead to a war that would devastate the colonies. Impressed by British power, the Loyalists predicted an American defeat if the Patriots continued to lead the colonies toward armed confrontation. Defeat would ruin the colonial economy, ravage farms, destroy cities, and probably lead to a far more tyrannical form of British rule. The Loyalists did not like the Parliamentary taxes but were prepared to pay them if the alternative was mob rule and a destructive and futile civil war.

During the summer of 1774 2 old friends took a walk together to discuss the political crisis. Both were lawyers, but John Adams had become a Patriot while Jonathan Sewall remained loyal to the empire. During their walk, Sewall warned Adams, "Great Britain is determined on her system. Her power is irresistible and it will certainly be destructive to you, and all those who...persevere in opposition to her designs." Adams replied, "I know that Great Britain is determined in her system, and that very determination determined me on mine. I have passed the Rubicon; swim or sink, live or die, survive or perish with my country that is my unalterable determination."

John Adams supported the idea of a new country named America, but his was a bold and dangerous position. No such country yet existed, and it seemed unlikely to hang together given the long history of the colonies bickering with one another. Naturally, many colonists balked at taking that risky leap. Unlike Adams, most Patriots still hoped that they could stay in the British Empire, provided that it would stop taxing them.

In April 1775 war erupted in battles at Lexington and Concord just outside of Boston. In command at Boston, General Thomas Gage sent out troops to seize gunpowder stored in the countryside; the local militiamen attacked and drove the British back into the seaport. Several thousand more militia from throughout New England rushed to besiege the British troops in Boston.

In May the Continental Congress gathered again in Philadelphia. To the immense relief of the New England delegates, Congress took responsibility for fighting the British, which meant that men from the Middle Atlantic and Southern colonies would march north to join the siege of Boston. To command the army, Congress appointed George Washington of Virginia. Thanks to his service on the frontier during the Seven Years' War, he had much military experience. He also came from the largest and most important colony, Virginia, an important political consideration as Congress sought to unite the colonies. The ragtag army besieging Boston became known as the Continental Army.

Still Congress did not declare independence. Although they were fighting the King's troops, the Patriots kept insisting that they would stop and go home if only the British would back down and withdraw their troops, the Coercive Acts, and Parliament's taxes on the colonists. A majority in Congress still preferred to reconcile rather than sustain a long, hard war for independence against the world's most powerful empire. Congress members also knew that the colonial economy depended upon maritime trade with the empire. And they feared that a new union of 13 colonies would collapse under the strains of war. Even those who favored independence wanted to wait until they could build more popular support for that risky move.

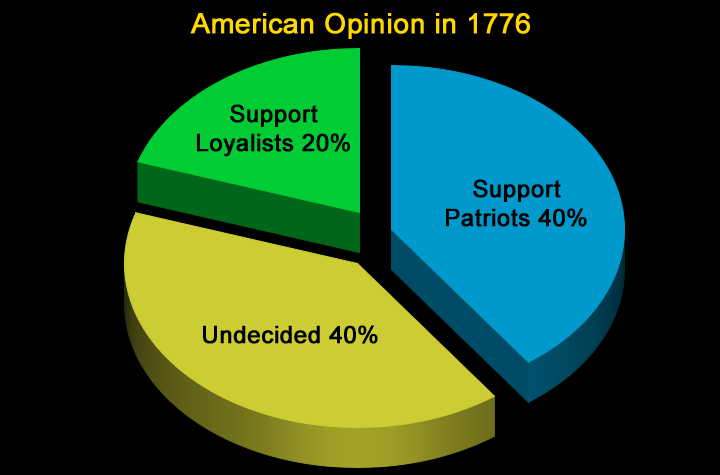

Americans were far from united in 1775. Two-fifths of the people were probably Patriots prepared for independence. Another fifth of the population fought as Loyalists to preserve the union of the empire. The remaining two-fifths remained politically on the fence and just wanted to be left alone in their neutrality.

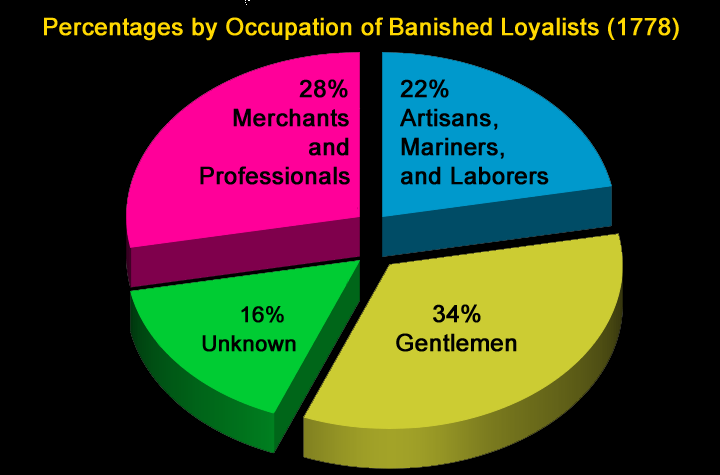

Stereotype casts the Loyalists as just a few stuffy and wealthy gentleman holding lucrative offices from the British Empire. Some leaders fit that description, but most Loyalists were farmers and artisans, as were most of the Patriots. The common Loyalists felt harassed by Patriot committees and mobs enforcing the Continental Association and forcing men to join local militias to fight the British. Some common people felt that the Patriots demanded more in taxes and permitted less free speech than did the empire. In Maryland, a farmer declared, "It was better for the poor people to lay down their arms and pay the duties and taxes laid upon them by King and Parliament than to be brought into slavery and to be commanded about as they were."

Loyalism also appealed to African Americans held in slavery and to Indians on the frontier. With British help, the Indians wanted to drive back the settlers pressing into the Ohio Valley, especially Kentucky. The enslaved hoped to win freedom by running away to join the British army. They considered the British, and not their Patriot masters, to be the true champions of liberty.

In January 1776 one popular book helped rally a majority in favor of independence and a republican government for a new American union. Entitled Common Sense, the book was written by Thomas Paine, a recent immigrant from England. Paine denounced monarchy and aristocracy as frauds that exploited the common people. Instead, common people should rule themselves in a republic: an elected government with neither king nor lords. He insisted that society would become almost perfect if people could choose all of their leaders: a very new and radical idea in 1776.

Paine expressed what many Americans had begun to want to believe. In Massachusetts, a Patriot remarked, "Every sentiment has sunk into my well-prepared heart." Common Sense was the first great American bestseller, with at least 150,000 copies sold. Thirty years later John Adams looked back and observed that no man had had "more influence on the world's inhabitants or affairs for the last thirty years than Thomas Paine."

Paine persuaded the Patriots and most of the wavering that they should support independence, union, and a republican form of government. On July 2, 1776, Congress voted for independence and, two days later, adopted the famous declaration drafted by Thomas Jefferson of Virginia. The declaration began with the proposition, "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness."

Few members of Congress had fully thought through the radical implications of those words. Indeed, most owned slaves, and none in Congress wanted to grant political rights to women. During the decades ahead, Americans would disagree over the true meaning of the idea "that all men are created equal." Meanwhile, the Patriots had their hands full trying to win the independence that they had declared.