Brief History of the Emergence of the American Constitution

Note to students: The best preparation for taking the reading quiz is to pay close attention to the key terms as you read. Each question in the question banks is directly linked to these key terms and phrases.

Chapter Focus Question:

What led to the emergence of the US Constitution and what are its chief features?

- Ideas contributing to American Constitution

- British unwritten constitution

- The one; the few; the many

- British bipartite legislature

- Oligarchy

- More British colonists could vote

- Women lack voting power

- No aristocracy in British America

Section Focus Question:

What are the features of the British unwritten constitution and how did Americans respond to that government in the American revolution?

Key Terms:

When the Founders considered writing a Constitution, they did not think in a vacuum. They were for the most part Englishmen, familiar with the workings of the British Parliament and the relationship between Parliament and the constitutional monarchy that had emerged in Great Britain from the mid 17th century. They also understood the theories of government upon which the British constitutional system were based. And they were acutely aware of the various political and moral philosophies for the improvement of government of both French and British thinkers of the European Enlightenment (1730-50). Moreover, they had spent most of their lives participating in the colonial government of the British colonies, which was quite robust and fairly democratic. Therefore, we can say that the structure of the American Constitution “emerged” even before the members of the Constitutional Convention put pen to paper in 1787-89.

The British Constitutional Tradition

The colonists had grown up hearing and believing that the British constitution was the finest in the world. Unlike the later American federal constitution, the British constitution was not a written document but instead a consensus understanding of the political institutions of the realm. According to prevailing political thinking, Britons enjoyed an ideal mixed constitution which preserved a balance between the three elements in any proper society: the one (the monarch), the few (the aristocrats), and the many (the common people). The monarch (usually a king, sometimes an unmarried queen) led the executive branch while the British had a bipartite legislature: the House of Lords for the few and the House of Commons to represent the common many (but only those with enough property to qualify to vote).

Political thinkers regarded a mixed constitution as better than a tyranny (the rule of one man), an oligarchy (the rule of the few), or a democracy (the rule of the many). A tyrant or oligarchy would rule the common people with an iron fist, while a democracy would lead to anarchy. At that time, educated people regarded democracy as a negative word. They feared that unscrupulous politicians known as "demagogues" would grab power and encourage the poor majority to plunder the rich minority.

According to political theory, only a mixed constitution could provide the proper checks and balances to preserve stability. The king, aristocracy, and commons would have to cooperate in Britain's mixed constitution to produce the common good while preserving the right degree of liberty for everyone. This was the conventional political wisdom believed in the colonies as well as in Britain before the American Revolution. Such a mixed constitution made sense in an empire where people were not equal in their property, civil rights, or political influence.

American Colonial Government

The colonial governments were supposed to operate as subordinate versions of the British constitution with a royal governor, appointed by the king, to represent the monarch, and with an elected assembly modeled on the House of Commons. The third institution was a council comprised of men nominated by the local assembly and approved by the royal governor. Every colony, even tiny Rhode Island, had its own government and there was no coordinating body within the colonies to unite them.

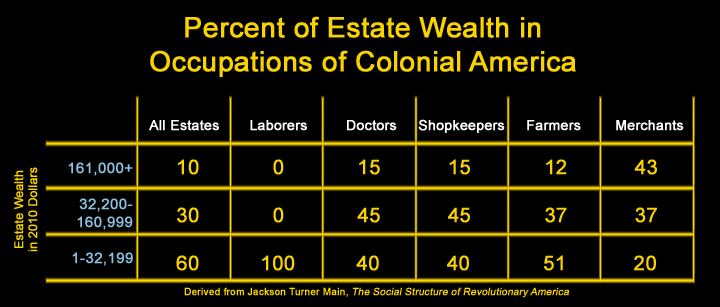

The colonies deviated from British society in two ways that kept the colonial governments from functioning according to proper political theory. First, when compared to the electorate for Parliament, in America many more men qualified to vote for representatives to the colonial assemblies. Only freemen could vote in the colonies and Britain, and the same property requirement prevailed on both sides of the Atlantic: a man had to own enough property to support himself and his family in order to vote. To meet the requirement, a man needed his own farm or shop. Women had no political rights, even if they owned property as widows.

Only a quarter of English men owned enough to vote, but at least half and perhaps two-thirds of the freemen in America had political rights. The difference derived from the relatively thin population in the colonies, which meant that more common men owned farms and, therefore, could vote. As a consequence, the American colonial assemblies had a more popular and democratic style than did the British Parliament.

Most Americans had occupations and lands that gave them at least some wealth and, therefore, voting rights.

In a second key difference, the colonies lacked the true aristocrats to render the councils truly equivalent to the British House of Lords. In the colonies, there were no lords, dukes, earls, and marquises to inherit titles and large, landed estates worked by tenants. The colonies had plenty of rich men, but they were planters, lawyers, and merchants who relied on buying and selling property to make and keep their money. The wealthiest colonists relied on commerce rather than inheritance for their fortunes.

Members of the councils were thus richer versions of the merchants, lawyers, and planters who served in the assemblies. In political disputes the councils usually sided with the assemblies against the royal governor. As a consequence, British officials regarded the colonial governments as out of balance. Britons considered the colonial governments too republican, because the governor and the council did not cooperate to restrain the too powerful and too popular legislatures of the colonies.

American Government in the Revolution

- Continental Congress

- British unwritten constitution

- 3 forms of resistance to the British government

- Continental Congress directives to the colonies

- American support for American Revolution

- Estate wealth of Americans

- Percentage of British citizens who could vote

- Articles of Confederation

- Weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation

Section Focus Question:

What kind of government did the American revolutionaries form during and directly after the American Revolution?

Key Terms:

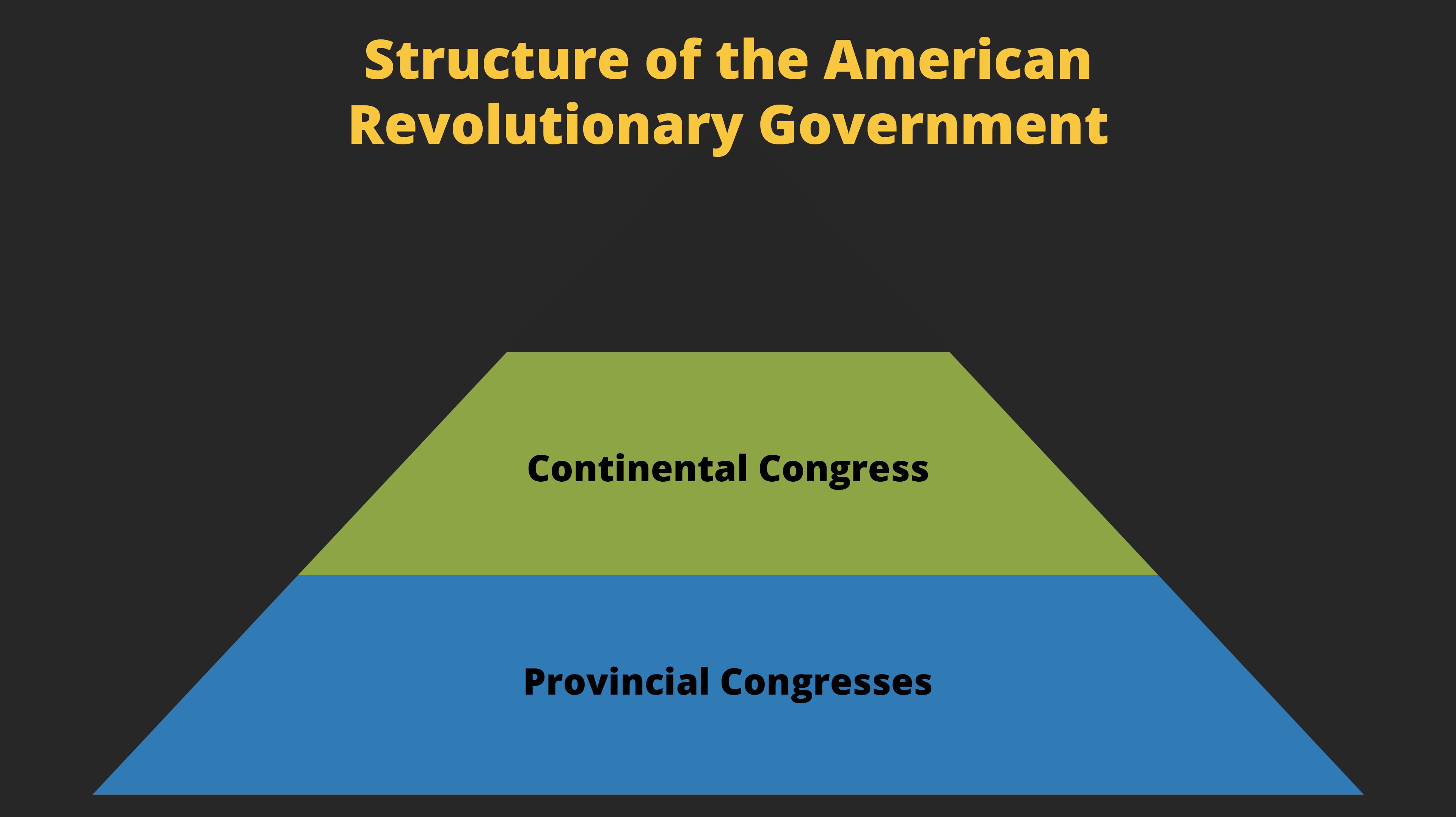

Once the revolution began, the various colonial assemblies sent delegates to Philadelphia to form a Continental Congress. It raised and organized financing for a colonial army and coordinated resistance in the states — boycotts, pamphlets, and even intimidation against British officials and Loyalists, or colonists who advocated staying in the British imperial fold. This First Continental Congress encouraged counties and towns to set up local committees to enforce the boycott and intimidate those who supported British policy. The emerging web of committees answered to new provincial congresses that emerged in every colony, and all looked for guidance to the Continental Congress.

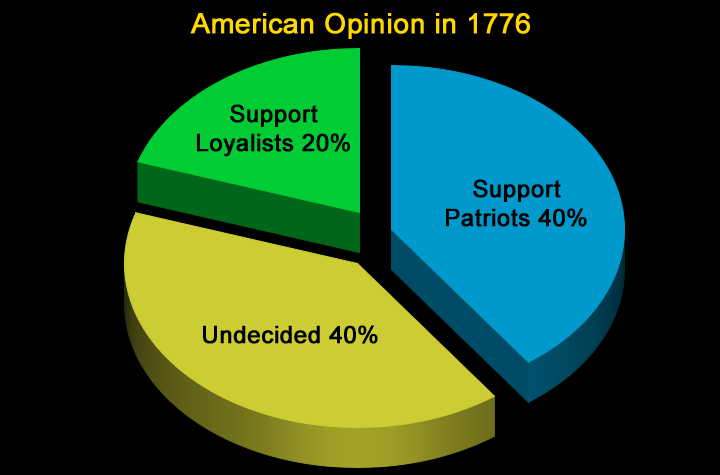

Americans were far from united in 1775. Two-fifths of the people were probably Patriots prepared for independence. Another fifth of the population fought as Loyalists to preserve the union of the empire. The remaining two-fifths remained politically on the fence and just wanted to be left alone in their neutrality. With time and extraordinary determination, however, the Patriots managed to prevail. After seven long years, the American revolutionary army, with the help of the French navy, defeated the British army at the Battle of Yorktown. Great Britain sued for peace in 1783.

The Articles of Confederation, 1781-89

The victorious Patriots had won their independence, but they continued to struggle to stabilize their new state republics and collective Union. Known as the “Articles of Confederation,” the first American, federal constitution went into effect in 1781. Essentially, it continued to rely on the Continental Congress that had been coordinating the state governments since 1775.

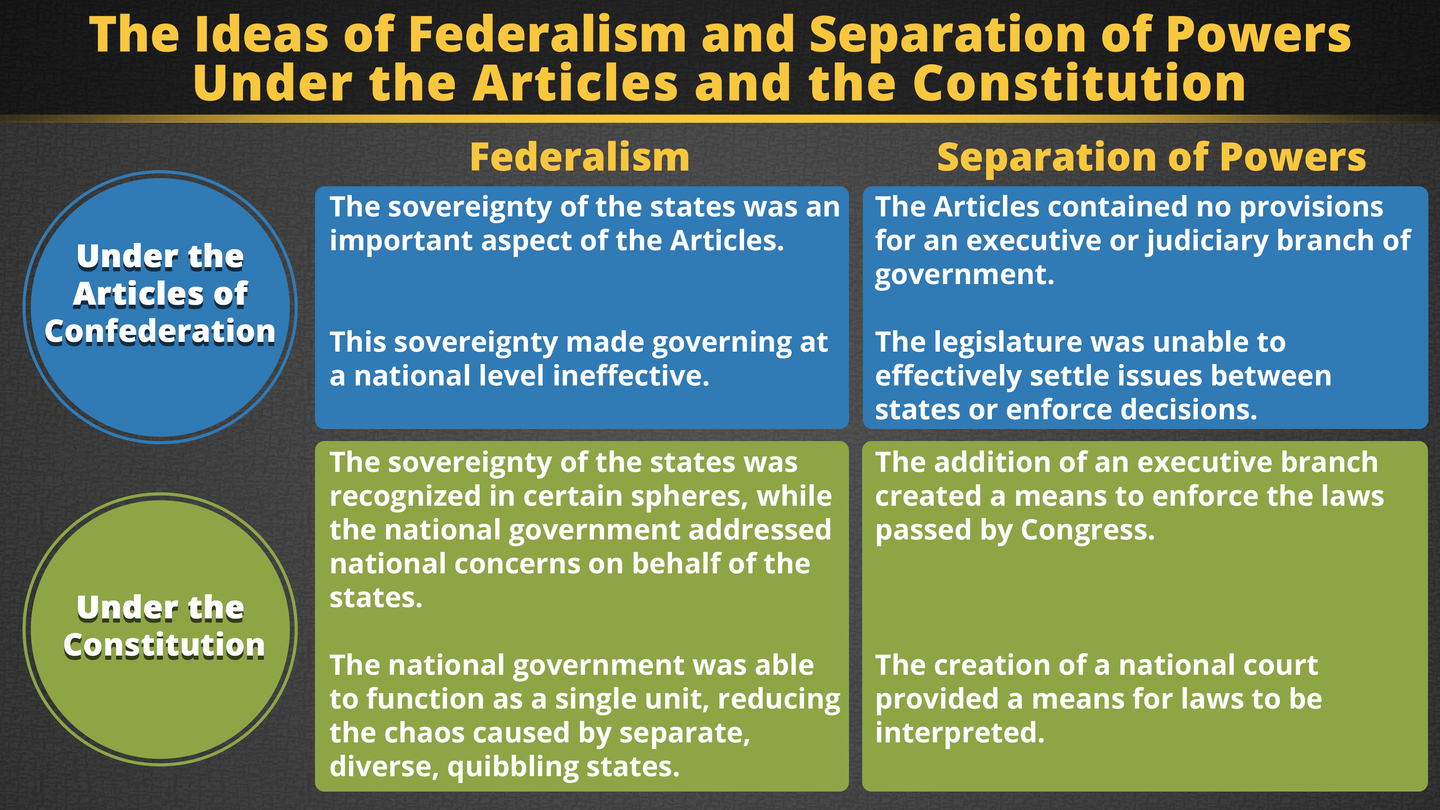

The Articles of Confederation established a weak confederation of 13 states rather than a truly consolidated nation. The states had conceded a few limited powers to Congress: to conduct diplomacy, wage war, regulate Indian affairs, coin and borrow money, and settle disputes among the states. But Congress remained weak, lacking the power to levy taxes, relying instead on contributions from the state governments. During the war, the states usually paid up. After the war, they found excuses to keep their money, depriving the confederation of the funds needed to pay its debts and to pay an army and navy.

The confederation government also lacked a president, relying instead on several committees of members of Congress to provide a weak and decentralized executive. Each state, no matter how large or small, had a single vote: enormous Virginia and tiny Rhode Island had the same power in Congress. On some issues a majority of seven states could pass laws, but on the biggest issues, including making treaties or declaring war, nine states had to approve. Any amendment to the Articles would require the consent of every State.

The American Constitution, 1787-92

- American Constitution developed in 1787

- James Madison

- Framers' principles

- Bill of Rights

- 3 defining characteristics of the American Constitution

- 9th Amendment

- The Great Compromise

- Factionalism and corruption in the legislature

Section Focus Question:

What kind of government did the American revolutionaries form during and directly after the American Revolution?

Key Terms:

By 1787 most Americans recognized that the confederation was failing for want of the powers to tax and to regulate interstate and international commerce. During the mid 1780s, the nation suffered a great trade recession, which had provoked armed conflict in some states between hard-hit debtors and their creditors.

In the spring of 1787, 12 of the 13 state governments (all but Rhode Island) sent delegates to Philadelphia for a special constitutional convention, which lasted through the summer of 1787. Most of the delegates agreed to scrap the Articles of Confederation and to adopt a new federal constitution to create a more truly national government that could control the states. Following the lead of James Madison of Virginia, the “Federalists” crafted a constitution with a strong president at the head of the executive branch. The new constitution also mandated a bicameral legislature: a Senate, where each state had two seats, and a House of Representatives, where the more populous states enjoyed more seats and, so, more power.

The new federal government sought to combine the core principle of republicanism — the reliance on elections to choose leaders—with the lingering traditions of the mixed constitution: especially a system of checks and balances between the political institutions. The founders expected the wealthy and well-educated (the closest thing the Americans had to an aristocracy) to dominate the Senate; the common people would elect the House of Representatives; and the President would have many of the powers, if not the hereditary status, of the British king.

To promote ratification of the proposed constitution, the Federalists relied on specially elected state conventions rather than the existing state legislatures which stood to lose power. The Federalists also insisted that the new constitution would go into effect as soon as nine states (rather than all 13) ratified it.

The federal constitution faced heated opposition from “Anti-federalists,” who preferred stronger state governments and a weaker nation. In a contentious process that began in September 1787 and lasted through June 1788, 11 states ratified (often narrowly). The Federalists appeased much of the opposition by promising to adopt a Bill of Rights once the new Congress convened. In early 1789 a new federal government led by President George Washington took office. Congress promptly crafted a Bill of Rights, which the states quickly approved. By protecting civil liberties, the Bill of Rights persuaded the holdout states — Rhode Island and North Carolina — to ratify the constitution and join the Union.

Defining Characteristics of the American Constitution

The Federal Convention had been called to correct the manifest defects — or what James Madison called “the vices” — of the Confederation. It might have done that simply by giving the single-chamber Continental Congress a limited set of additional powers. Instead it proposed vesting a significant number of legislative powers in a bicameral Congress that could act directly on the citizens of the United States. That fundamental change required rethinking the basic nature of the national government. In the process of the convention, three defining characteristics of the American Constitution emerged — the supreme authority of a written constitution, the creation of a federal system in which both the national and state governments would legislate for their citizens, and the separation of powers across three independent departments.

The Supremacy of the Constitution. The leading Framer at the Constitutional Convention, James Madison of Virginia (who later became the 4th president of the United States), believed that one of the worst vices of the Articles of Confederation was the presumption of voluntary compliance by the states with the federal government. Madison found that federalism based on the voluntary compliance of states would fail. Experience showed that many states would not enforce national laws. The states would combine together and actively opposed some policies. Even when states agreed, doubts about their level of commitment slowed the system.

Madison did not want to keep a federal union hobbled by unsupportive states. He wanted a national government that would pass laws that would directly bind citizens. Thus, the federal Constitution had to be the supreme authority in the land. In practice, when a state law differed with a power reserved to the federal government in the Constitution, the federal government would prevail. Of course, those powers not reserved to the federal government, as written in the Constitution, were presumed to be reserved to the states. This was reiterated in the 9th Amendment to the Constitution.

The Supremacy Clause of the Constitution

This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.

Federalism. Anti-federalists were deeply worried that the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution would take away all powers of the states. But, at the convention, they managed to protect state interests in two ways. First, though Madison wanted Congress to have the final authority to determine if a state law undermined federal laws, the delegates at the convention vested the right to make this determination in a third independent party — the judiciary.

Second, the smaller states made sure that they had sufficient representation in Congress to preserve state interests. Madison wanted representation in Congress solely by population and won this point with the formation of the House of Representatives. The population was divided into equal districts of set numbers and a representative would be elected from each district. However, the anti-Federalists and smaller states prevailed in the Senate. Each state would receive two representatives regardless of the population of the state. And the original Constitution provided that these Senators would be elected by state legislatures (until it was amended in the early 20th century by the 17th Amendment).

The tensions between the state and federal governments have been an ongoing struggle since the founding of the republic. It can be said that the stronger federal government that the Federalists wanted has been more on the rise, especially in the 20th century. Nevertheless, these two early victories that allowed the judiciary to determine the line between state and federal government jurisdictions and that built state influence into the federal representation system have been effective two checks on federal government.

Separation of Powers. At the time of the Constitutional Convention, the Framers were greatly focused on legislative power. Article I of the Constitution is the longest section and explains in great detail the composition and structure of the Congress. Article II sketchily defines the presidency, and Article III barely describes the powers of the courts and judges of the federal system. The Framers did not have particularly well-formed ideas about how the executive would work. In fact, a president was an entirely new concept that they were inventing. They paid little attention to the judiciary and seemed to believe that it would operate as it did in the colonial period, except for the founding of the Supreme Court, which was also a new institution.

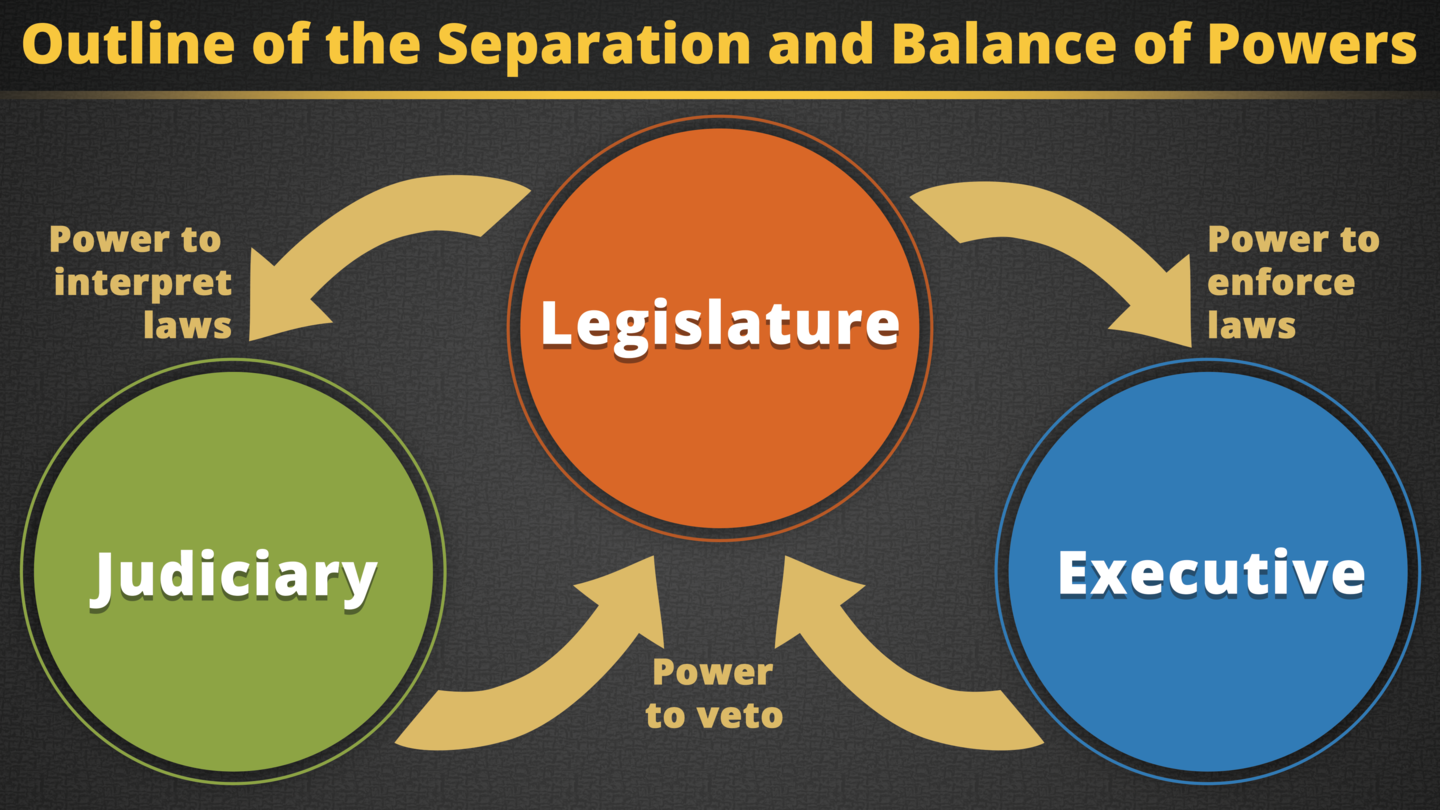

They understood, nevertheless, that these weaker branches needed to have the ability to check the overall power of Congress. In enumerating the powers of the presidency, they seemed to see the executive as a leader in foreign policy matters and the civilian commander of the military. Nevertheless, the Founders gave the President an extremely important check on Congress, which was his veto of legislation that could only be overturned by a two-thirds majority vote of the Congress. For the courts and particularly the Supreme Court, the Framers reserved the power to rule on the laws, and very importantly the jurisdiction between state and federal laws that governed federalism itself.

Over time, the presidency and the the courts have extended their powers, but this was not foreseen in the late 18th century. Instead, the Framers were preoccupied with containing corruption and factionalism within the powerful Congress, fearing that it might lead to tyranny as predicted by political philosophers of their time and their own experiences in colonial and state legislatures. Therefore, they firmly divided power between the two houses of Congress — the House of Representatives and the Senate — such that legislation would have to run an arduous gauntlet from the popularly elected House, through the state-elected Senate, and to the signing of the President before becoming law. Even after enactment, it might have to survive reviews in the Supreme Court.