The Rapid Rise of New Economies and Societies

Note to students: The best preparation for taking the reading quiz is to pay close attention to the key terms as you read. Each question in the question banks is directly linked to these key terms and phrases.

Chapter Focus Question:

How did the economies of the northern and southern colonies differ?

- Cheap or free American land

- German immigration

- European/Native trade

- Jamestown

- Plymouth

- Difference in land use of the colonies

- Cost of labor

- Slavery

Section Focus Question:

Why was labor so highly prized in American colonial communities?

Key Terms:

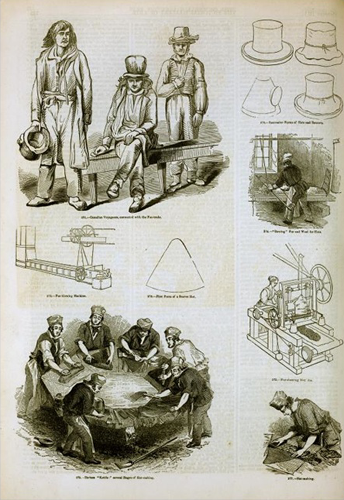

The economies and societies created by the colonists were not replicas of the European and African worlds they left behind, nor were they uniform across the regions of British America. For Indians as well, colonial British America was a new world in social and economic terms. Early European outposts in America linked Indians for the first time to overseas markets for their own products and introduced Indians to new foreign goods. For example, the skins and fur of animals such as deer and beaver that Indians hunted for their own use rapidly gained a fashionable following when brought to Europe.

European demand created pressure from traders on Indian hunters to procure ever larger quantities of these items. In return, traders provided new items — iron and steel tools, woven textiles — that Indians found equally appealing. Consequently, both Europeans and Indians adapted their familiar economies to these new forms of supply and demand.

In some Indian communities, skill in hunting gave young men greater access to coveted trade goods from European traders. It recast the balance of power in Indian societies away from elders or from matrilineal forms of decision-making. Similarly, growing Indian dependence on European manufactured goods for clothing and cooking and the introduction of alcohol and firearms to Indian societies also reshaped older patterns of work and power relations.

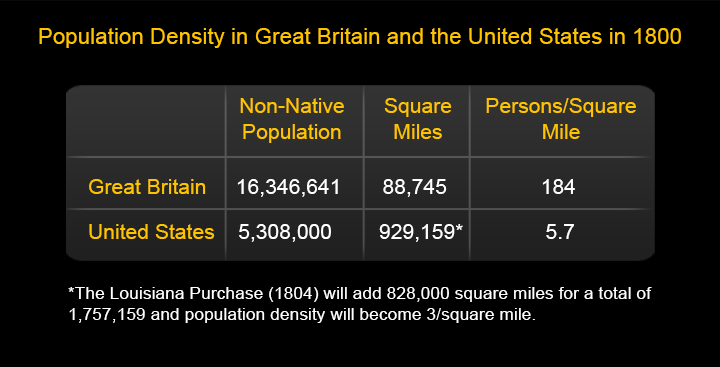

If there was a single social and economic condition that all of Britain's American colonies shared, it was the fundamental reversal of the traditional relationship between land and labor in European life. In Europe, land was scarce and expensive, and people were plentiful and cheap. There were too many workers and not enough work to do, so wages for workers were low. In America, the opposite seemed to be true.

Provided that colonists were willing to push Indians out of the way, land resources appeared to be inexhaustible. But there was a chronic shortage of the workers necessary to make the land profitable. Wages for free workers in America were high, and free workers often had a strong desire to become landowners themselves, to be their own masters.Consequently, many landowners were willing to pay high prices for unfree labor — either indentured servants or slaves — to control a large and reliable working force for long periods of time.

After the first brutal years of colonization, in which migrants learned to adjust to the new environment, mere survival was not that difficult. North American land was fertile and food grew readily. But few colonists wanted to abandon their European homes and cross the wide ocean simply to eke out a meager living. The promise of colonization lay in the prospect of improving life, to grow richer or to live better in the New World than in the Old. Every colonial region looked to discover new ways to profit from the land, but each region found a different way to do this.

- Tobacco

- Rice

- Sugar and South Carolina

- New England food trade

- Slavery

Section Focus Question:

What were the characteristics (labor, land, crops) of the plantations of the Caribbean and southern North America?

Key Terms:

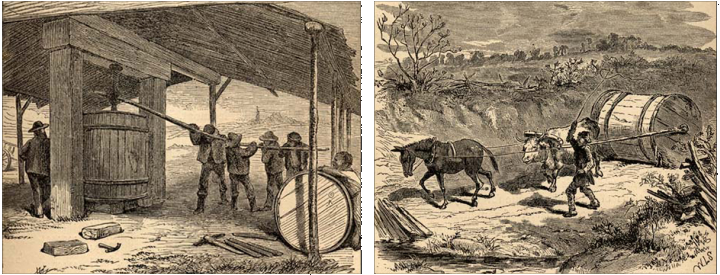

In the Caribbean colonies and the southern parts of the mainland, the production of valuable staple crops became the dominant economic pattern. In the West Indies, sugar cane could be grown and processed into sugar, molasses, or rum that fetched high prices on the European market. Plantation owners converted all the land at their disposal to sugar production, paid high prices to purchase the labor of slaves for life, and imported the food and clothing necessary to keep their workers going.

This was, in effect, an industrial economy, a farming monoculture so intense as to chew up its African workers and benefit only a tiny handful of elite English owners and operators of the system. In per capita wealth, the West Indies was easily the richest region of colonial British America. But that wealth was concentrated in the hands of a few, who often moved back to England to enjoy their money as far from the brutal scenes of its production as possible.

South Carolina attempted to replicate the sugar production of Barbados, but the climate could not sustain it. As white plantation owners searched for alternatives, enslaved Africans introduced the cultivation of rice, a common crop in parts of West Africa. It soon became one of Carolina's primary products (while indigo, a plant used to dye textiles blue, was the other).

Although not as profitable as sugar, Carolina rice nonetheless allowed planters to import large numbers of enslaved Africans to the coastal lowlands and Sea Islands. Africans soon came to outnumber the English by ratios of at least 2:1 in the 18th century. Large plantation owners, whose estates employed dozens if not hundreds of slaves, congregated in Charleston where they built elegant urban homes and dominated colonial society.

In the tobacco growing regions of North Carolina, Virginia, and Maryland, a different form of plantation society developed. After the initial boom years of the 1620s and 1630s, when tobacco's novelty made it all the rage in England, the value of this crop settled in to a steady if unspectacular source of profits. Some plantation owners, especially those who got into the game early and engrossed large amounts of the best land along the Chesapeake's navigable rivers, became very wealthy and accumulated hundreds of slaves to work their plantations.

But far more plantations, especially those far from the rivers or the coast, were small, owned and worked by a farmer, his wife and children, and perhaps one or two slaves. As a result, Chesapeake plantation society looked very different from that of the Caribbean or Carolinas. In Virginia and Maryland, English masters and their African slaves lived under the same roof and worked side by side in the same fields. These family-based plantations grew their own food for consumption as well as tobacco for the overseas market. They were often dependent on the larger plantation owners to market their tobacco and supply them with imported goods.

- Slavery and New England

- Colonies’ connections to Great Britain

- Triangle Trade

- British dominance in North America

- Farming dominance in the colonies

- Egalitarian society of the colonies

Section Focus Question:

What were the characteristics of the northern farms and fisheries, and how did they develop and prosper from an inter-colonial trade, especially with Barbados in the Caribbean?

Key Terms:

North of Maryland, it was still the case that there were enslaved Africans forced to labor in every English colony. But aside from a few small and distinctive regions (such as the Narragansett area of western Rhode Island), enslaved Africans in the northern colonies made up a small portion of the labor force. None of the high-priced staple commodities, not even tobacco, grew well enough this far north to provide most landowners with profit margins necessary to purchase a slave's labor for life. Instead, farmers in the north generally made do by utilizing the labor of their own families — their wives and children or by "renting" the labor of servants when necessary.

The northern colonies' most distinctive economy developed in New England, and in a way that made it unlike any of the other British colonies. With a cold climate and rocky, unyielding soil, New England farmers could not produce any commodities that England did not already have. It was impossible to exchange their products for imported English goods.

However, the sugar monoculture of Barbados and the West Indies became New England's salvation. Because they imported food, timber, and other humble commodities that New England's farmers and fishermen could produce, the West Indian plantations became the market for New England goods. In turn, the inter-American trade became the source of credits that New England merchants could exchange in England for imports.

Consequently, New England developed a trade system across the Atlantic including itself, England, and the British West Indies called a "triangle trade." Enterprising merchants in the region's capital city of Boston put the labor of farmers and fishermen to work to create a complex economy more reminiscent of England's than of the other staple colonies. During the later 17th and 18th centuries, the richer and more plentiful lands of Pennsylvania and New York were opened up to new migrants. Soon the cities of Philadelphia and New York began to imitate Boston in linking the products of the countryside to the markets of an expanding Atlantic world.

Everywhere in Britain's American colonies, the vast majority of the population lived on farms and worked in agriculture, men and women, old and young alike. Less than five percent of the colonial population lived in towns of even 2,000 people or more. Yet the character of these agricultural societies varied enormously across the colonies.

The southernmost colonies in the West Indies and South Carolina fostered a form of intense and brutal agriculture. The great bulk of the population consisted of forced labor and worked so hard as to be unable to reproduce themselves, all for the benefit of an elite few.

In the northern colonies, from New England through Pennsylvania, New York, and New Jersey, landowning was widespread. Families worked the land they owned, and a society developed on terms more egalitarian than anywhere in Europe at the time, although the traditional hierarchies of gender and age within families remained unchanged.

The small farms, wide land distribution, and local food-production of the tobacco regions may have resembled on the surface the condition of their northern neighbors. Nevertheless, the colonies from Maryland to North Carolina, with Virginia the largest of them all, were starkly divided between the white English owner-proprietors and the African slaves. The latter were forever excluded from the rights and liberties that came with property.