Adolescence

Note to students: The best preparation for taking the reading quiz is to pay close attention to the key terms as you read. Each question in the question banks is directly linked to these key terms and phrases.

Chapter Focus Question:

What are the causes of puberty, and what special behavioral and biological challenges do adolescents face as they travel the path to adulthood?

- Changes in adolescence

- Span of adolescence

- Puberty

- Puberty and ethnicity

- Prefrontal cortex

- Brain size

- Gray matter

- White matter

- Pruning

Section Focus Question:

What are the forces of change during puberty, and what role does brain maturity play?

Key Terms:

Adolescence is an exciting period of life during which significant development occurs in biological, neural, cognitive, and emotional domains. Across different cultures and species, adolescence serves to help transition individuals from a state of dependence to one of independence from caregivers.

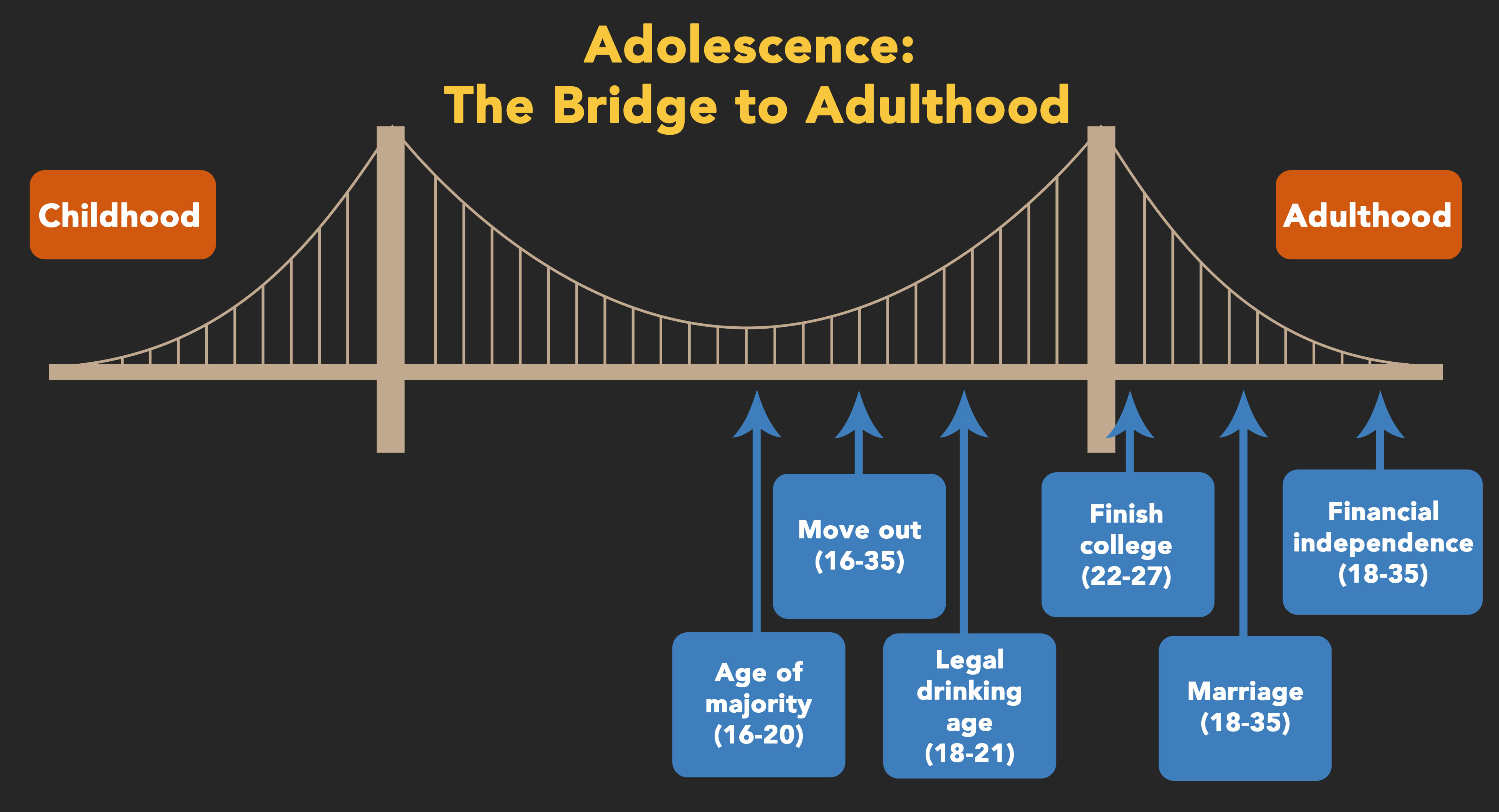

The period of adolescence is surprisingly difficult to define because its definition includes a confluence of biological and environmental factors. It begins when an individual undergoes puberty but its endpoint varies across cultures. In some cultures, adolescence ends and adulthood begins with marriage, whereas other cultures consider the end of adolescence when an individual leaves the family unit (e.g. going to college) or becomes financially independent.

Puberty

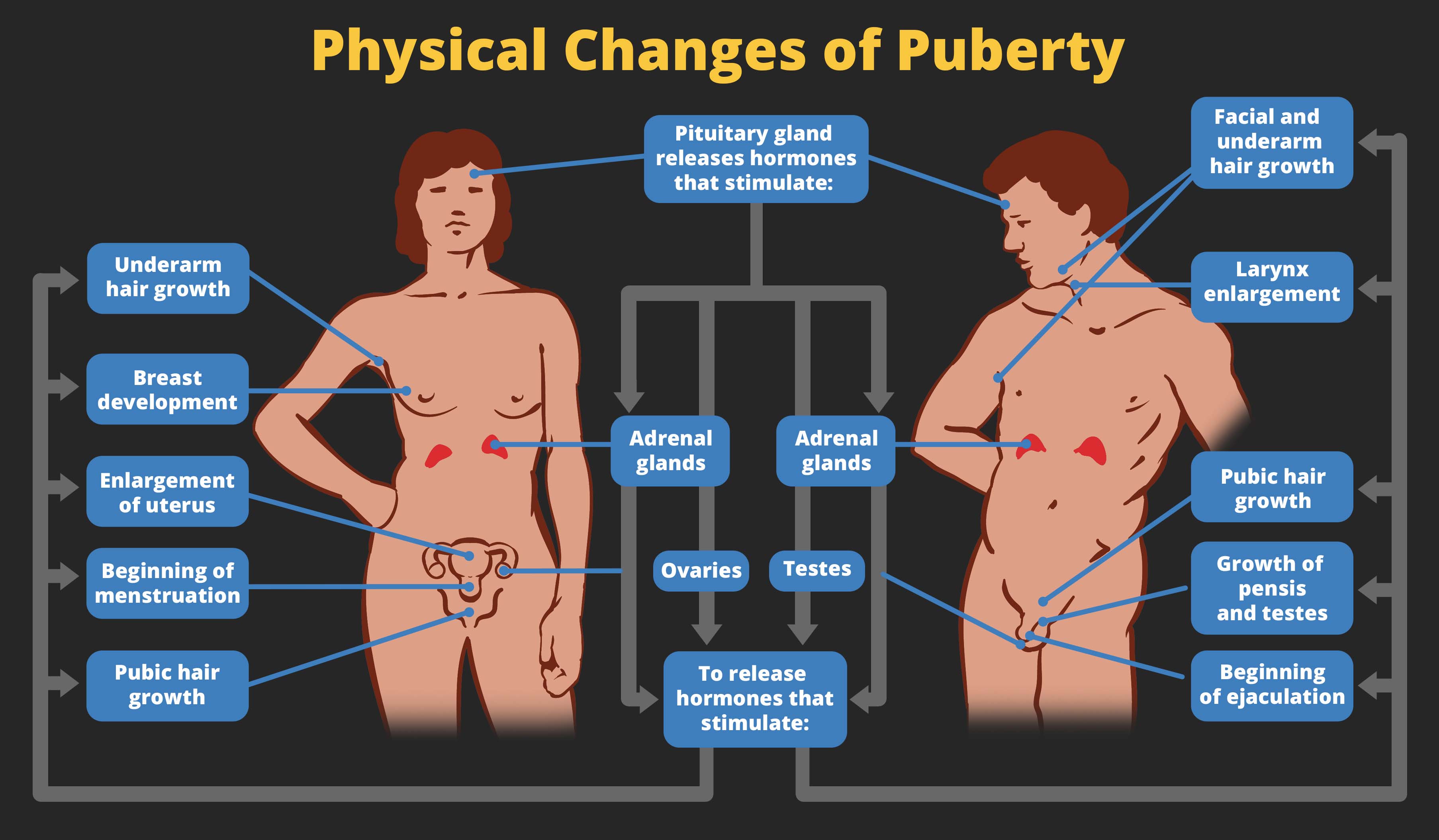

The end of childhood is marked by pubertal maturation. Puberty is the result of a series of hormonal events during which young adolescents undergo physical and hormonal changes. A massive growth spurt (both in height and weight) and increased testosterone, estrogen, and other pubertal hormones characterize puberty. These biological changes are often associated with marked changes in moods and behaviors. Although these behavioral shifts can sometimes frustrate parents, they are a part of the normal process of becoming an adult.

The release of pubertal hormones from a region of the brain called the hypothalamus jumpstarts the physical changes that precede reproductive maturity. In girls, these hormones stimulate the ovaries to release additional “estrogen,” which leads to breast budding, pubic hair growth, and “menarche,” the first menstrual period. In boys, the testes are stimulated to produce additional “testosterone,” which induces pubic and facial hair growth, enlargement of the testes, and a deepening of the voice.

The age at which individuals reach reproductive maturity has become increasingly earlier with each successive generation. Although the average age of the first period has not fallen much in the past 75 years, the age at which secondary sex characteristics (e.g. breast budding) emerge has generally declined. Scientists are puzzled about this trend but have speculated that it may be due to a number of factors, including changes in diet to one that is more caloric than in previous generations, higher levels of stress (which has been associated with triggering puberty), and other environmental chemicals.

Ethnic differences in pubertal timing have been consistently observed across different studies. For instance, one study found that significantly more African American (12.1 percent) and Latina (19.2 percent) girls had begun breast development by age eight than Caucasian girls (1.3 percent). Theories to explain these ethnic differences include genetic differences, dietary and activity differences, and variability in rearing environment. However, none of these theories have been proven, and the differences in pubertal timing remain a mystery.

Cognitive Development

Cognitive development refers to many mental abilities, including attention, self-regulation, memory, problem solving, language, reasoning, and decision-making. These skills mature throughout the course of childhood but undergo particularly robust development in adolescence. Some developmental theorists say that during this developmental window, adolescents become as “smart” as adults because they begin to exhibit sophisticated thoughts about abstract concepts, theoretical ideas (such as religion and time), and future planning.

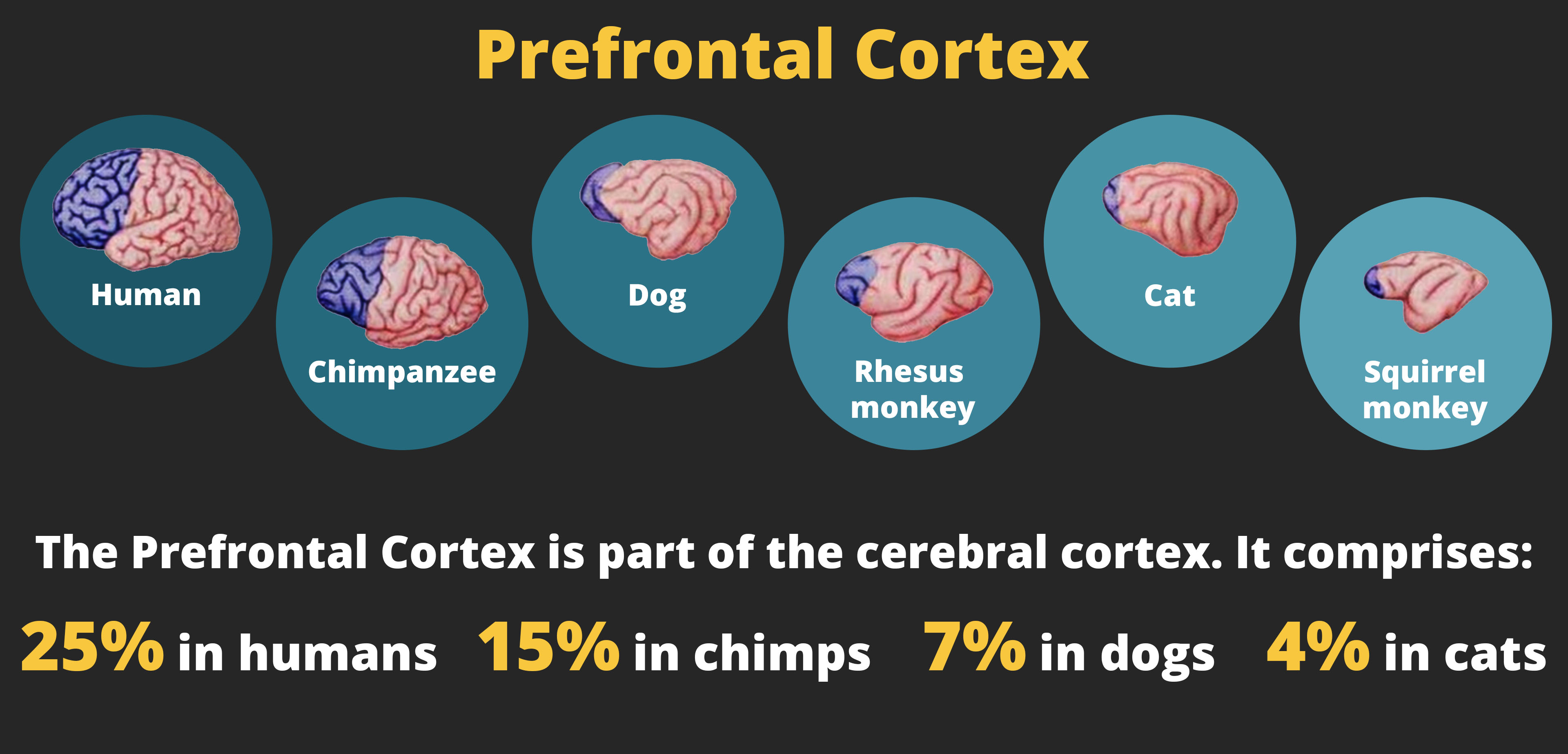

The development of higher cognition in adolescence coincides with significant maturation of a brain region called the prefrontal cortex. The prefrontal cortex is a large piece of brain tissue that is located on the top, most anterior part the brain. Although other (non-human) animals have a brain region similar to the human prefrontal cortex, no other animal has one that is as proportionally large, complex, and prominent as humans.

The human prefrontal cortex takes up much more space in the brain compared to other animals, taking up approximately 25 percent of all the cerebral cortex. By comparison, the prefrontal cortex-like brain region makes up only 15 percent in chimps, seven percent in dogs, and four percent in cats. Many years and hard work have been devoted to determining why humans have such a large and important prefrontal cortex. Scientists have come to the general conclusion that the human prefrontal cortex affords our species flexibility of behavior, which promotes sophisticated decision-making capabilities, goal-directed behavior, and working memory, as well as the spoken and written language.

The prefrontal cortex changes considerably in size and function from birth through death. It is the last brain region to develop, as the brain develops from the back, which houses regions important for basic skills such as breathing and walking, to the front. In fact, it has a longer period of development than any other brain region, taking over two decades to reach full maturity in humans.

The overall size of the brain does not actually change much beyond about six years of age. However, the connections between brain regions is what accounts for the protracted development of the prefrontal cortex. White matter, which is comprised of the fatty proteins that connect brain regions, continues to increase well into the mid-20s. Gray matter, which is comprised mostly of brain cells (neurons) matures first in sensory and motor areas and last in subregions of the prefrontal cortex.

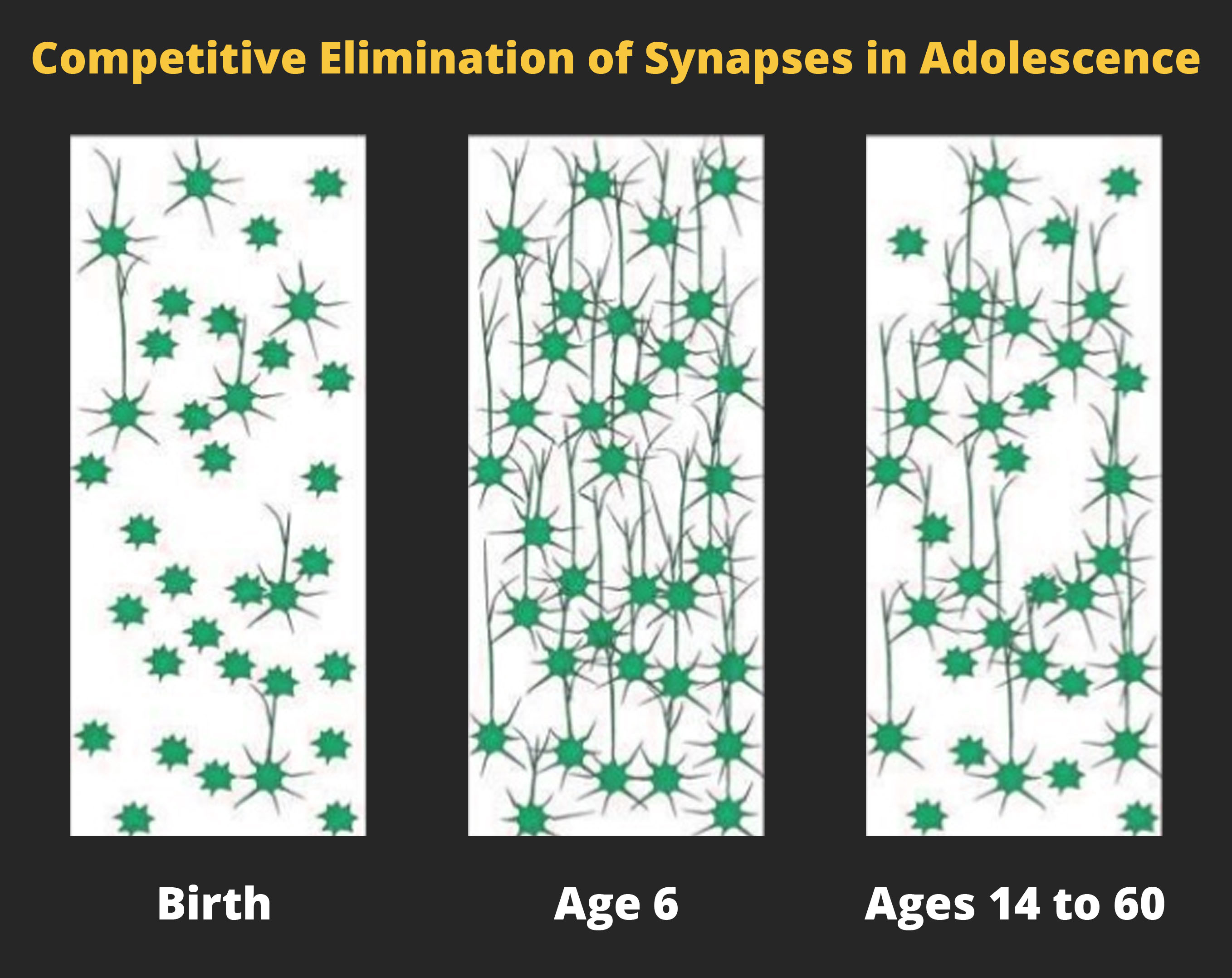

“Maturity” in this case refers to the brain’s internal process of eliminating unused connections between neurons — a process referred to as “pruning.” The brain overproduces neurons and connections between neurons (also called “synapses”) early in life but then, as based on each individual’s experience, begins to prune them away using the “use it or lose it” principle. The brilliance of this process is much like the pruning of a tree — by cutting back weak branches (connections), others have a better chance of thriving and surviving.

The pruning process also allows the brain to make room for new neurons and synapses that are borne out of individual experiences. Two brain regions, the hippocampus (important for learning and memory) and the olfactory bulb (responsible for smell), undergo neurogenesis (the birth of new neurons) throughout life whereas all brain regions have the capacity to make new synapses (the connections between neurons).

Social and Emotional Development

- Peer pressure

- Conformity

- Adolescent conflict with adults

- Scientific explanation for peer influence

- Peak substance use and abuse by age

- Adolescents and sleep

- Sleep deprivation

- Social jetlag

Section Focus Question:

What role does neurobiology play in peer pressure, and why do the strong emotions experienced by adolescents appear to flatten out in young adulthood?

Key Terms:

Popular notions of adolescence are that it is a development period filled with volatile emotion, impulse action, and minimal rational thought. This account of adolescent behavior is supported, in part, by scientific evidence. In one seminal study, researchers report that adolescents report positive emotions more than 70 percent of the time but that average happiness decreases from early to late adolescence because there is an increase in negative emotions during this time.

The decrease in emotional volatility that is observed as adolescents transition into young adulthood is the increased ability to regulate emotions. Emotion regulation improves because adolescents begin to have better psychological tools — including expressing their emotions and seeking social support — and because of the maturation of the prefrontal cortex, which helps dampen reactivity in emotion centers of the brain.

The increasing interest in social relationships that begin in middle childhood intensifies in adolescence. Adolescents spend twice as much time with their friends than with parents and other adults in high school. The bonds they strengthen help individuals navigate the sometimes challenging transition into adulthood. Some adolescents struggle with self-identity, finding their own clique, and the complexities of early romantic relationships. A good friend can help ease the emotional weight of these new adventures.

Many parents and adults also undergo “growing pains” of adolescence. The increased time spent with peers can sometimes lead teens to engage in behaviors simply because their peers are engaging in them — a phenomenon known as “peer pressure.” Extensive research has shown that adolescents exhibit high “conformity” (also known as “homophily”), which refers to the extent to which friends are similar to each other in their preferences, behavior, and aspirations for the future.

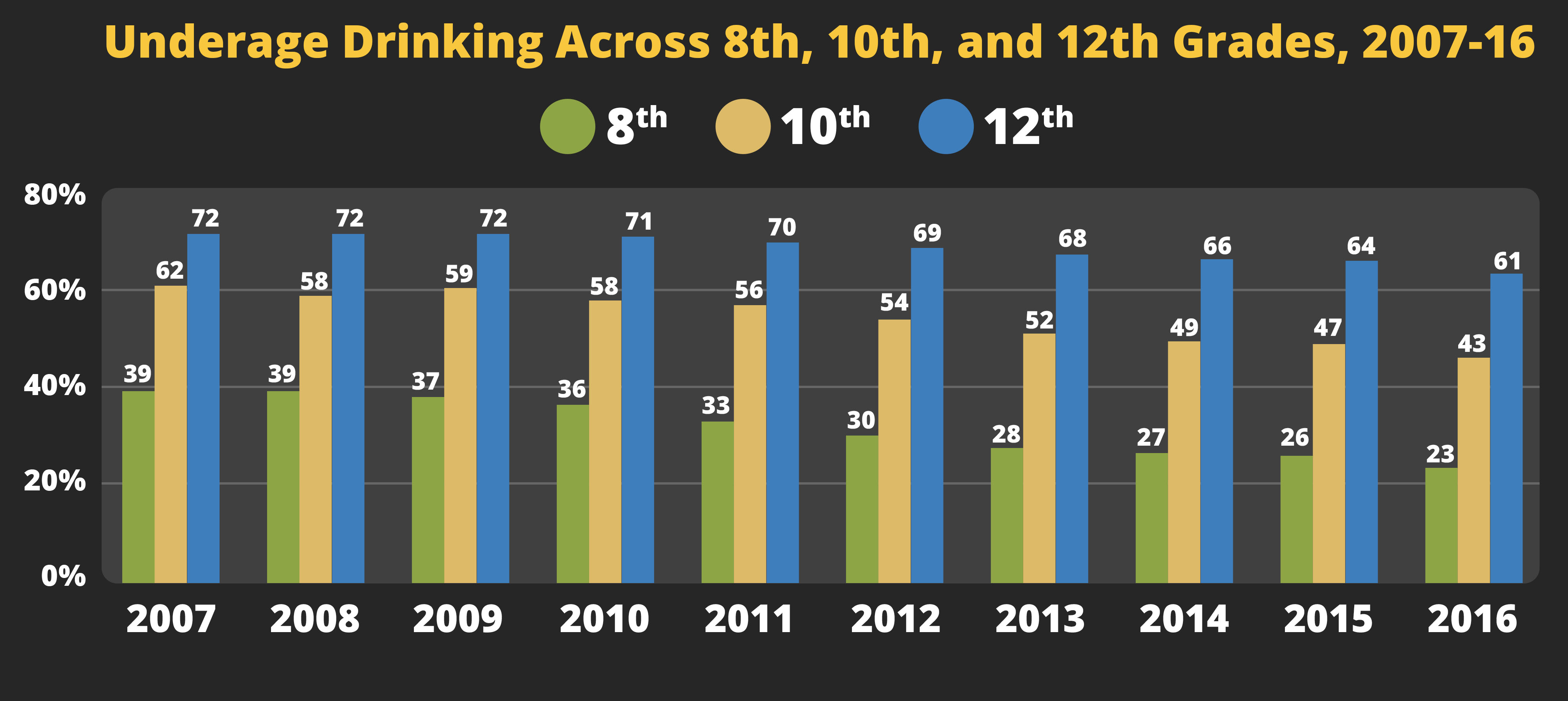

Sometimes conformity can serve to help adolescents seek out new positive adventures, strive for greater goals than they would on their own, and integrate social norms into their own behaviors. However, conformity and peer pressure can also lead to deviant behavior or risky choices. For example, researchers have reported that boys and girls whose friends engaged in a high level of deviant and disruptive behavior at the beginning of the school year reported an increase in their own deviant and disruptive behavior by the end of the school year. Studies on substance use have reported similar effects, such that adolescents are much more likely to smoke cigarettes, drink alcohol, use illegal drugs, be sexually active, or break the law if they socialize with adolescents who engage in these behaviors.

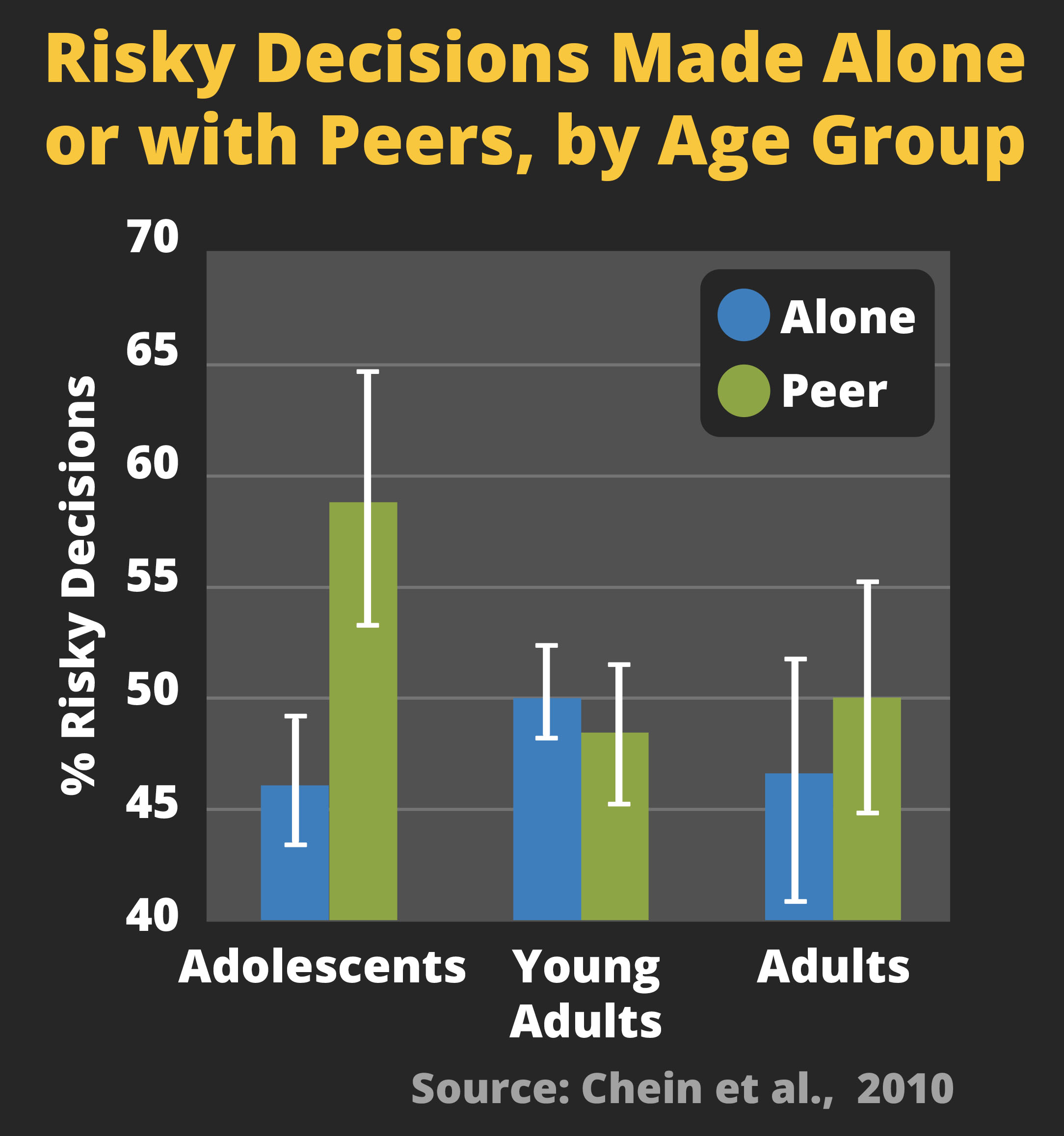

A seminal study by Steinberg and colleagues reported a neurobiological explanation for adolescent peer influence. In the study, adolescent and adult participants played a risk-taking video game in the presence of their peers while undergoing a brain scan (Chein et al 2010). Each participant played the game either alone or in the presence of two same-aged, same-sex friends. College students and adults made the same number of risky and non-risky choices whether or not there was a peer watching them. Not so the adolescents, who made greater risky choices when a peer was watching than when they were alone. Interestingly, risky decisions in the presence of peers elicited greater activation in the reward center of the brain in the adolescent group only. This study provides compelling evidence that in the company of friends, adolescents’ reward sensitivity is amplified when confronted with a risky choice.

The increased affiliation with friends often coincides with increased conflicts with parents. American adolescents spend about 50 percent less time with their families at the beginning of high school than they did in elementary school. Parents report that their teens become more distant and are more likely to seek out advice and support from their peers. Increased conflict between parent and child, about matters ranging from privileges to dating and financial independence, is also common. Luckily, the intensity and frequency of conflict wane from early to late adolescence. Although this period presents a challenge for parents and other concerned adults, conflict, and independence-seeking are all part of the normative interest adolescents have in becoming autonomous, achieving a mature identity, and exploring their environment.

Social and Emotional Problems

- Problems that emerge during adolescence

- Internalizing problems and adolescent girls

- Internalizing/externalizing disorders

- Adolescent onset externalizing problems

- Problems characteristically exhibited by adolescent boys

- Life-course persistent or childhood onset externalizing problems

- Adolescents and violent behavior

Section Focus Question:

What psychological concerns often present themselves during adolescence, and how telling is childhood onset of these problems for psychological difficulties later in life?

Key Terms:

The onset of psychological issues is greater in adolescence than at other times in life. The development of brain regions during adolescence that are responsible for emotion processing contributes to the high prevalence of these issues. Other factors include higher levels of stress, peer influence, and family conflicts.

The majority of adolescents struggle with symptoms of internalizing or externalizing disorders at some point in adolescence. However, identifying the extent and degree to which they impede day-to-day functioning is essential in assessing when to get professional help. There are two main classes of emotional problems that can be ameliorated through therapy, or in some cases, psychiatric medicine. “Internalizing problems, which are more common in girls, include disturbances in emotion or mood, such as those observed in depression and anxiety. “Externalizing problems,” which are more common in boys, include aggression, delinquency, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. In the early 2000s, it was noted that extremely violent or delinquent behavior is only committed by a small majority of adolescents.

In fact, 50 percent of all violent behaviors are committed by only six percent of adolescents. Based on extensive research, Moffitt and colleagues identified two highly distinctive groups of adolescents with externalizing problems. The “adolescent onset” group is characterized by behaviors that emerge in adolescence and disappear almost entirely by young adulthood. The second group, called “life-course persistent or childhood onset,” shows high levels of aggression well before adolescence, often in preschool, that persists throughout adolescence and into adulthood. The latter group is comprised of individuals who often go on to become “career criminals” and who had difficult upbringings and poor development of social skills.

Despite the potential challenges of adolescence, it should not overshadow the excitement and possibility of this period of development. With healthy role models, social support, and positive experiences, most individuals emerge from adolescence as confident and independent members of society.