Operant Conditioning

Note to students: The best preparation for taking the reading quiz is to pay close attention to the key terms as you read. Each question in the question banks is directly linked to these key terms and phrases.

Chapter Focus Question:

How has work in the fields of behavior analysis and operant conditioning conducted by psychologists Skinner, Thorndike, and Watson expanded our understanding of the origins and demonstration of human behavior?

- Law of Effect

- Edward Thorndike

- Operant conditioning

- Behavior analysis

- John B. Watson

- Observable behavior

- B.F. Skinner

- Skinner box

- Operant behavior

- Predict/control behavior

Section Focus Question:

What does operant behavior suggest about the way elements in the environment affect current and future behaviors?

Key Terms:

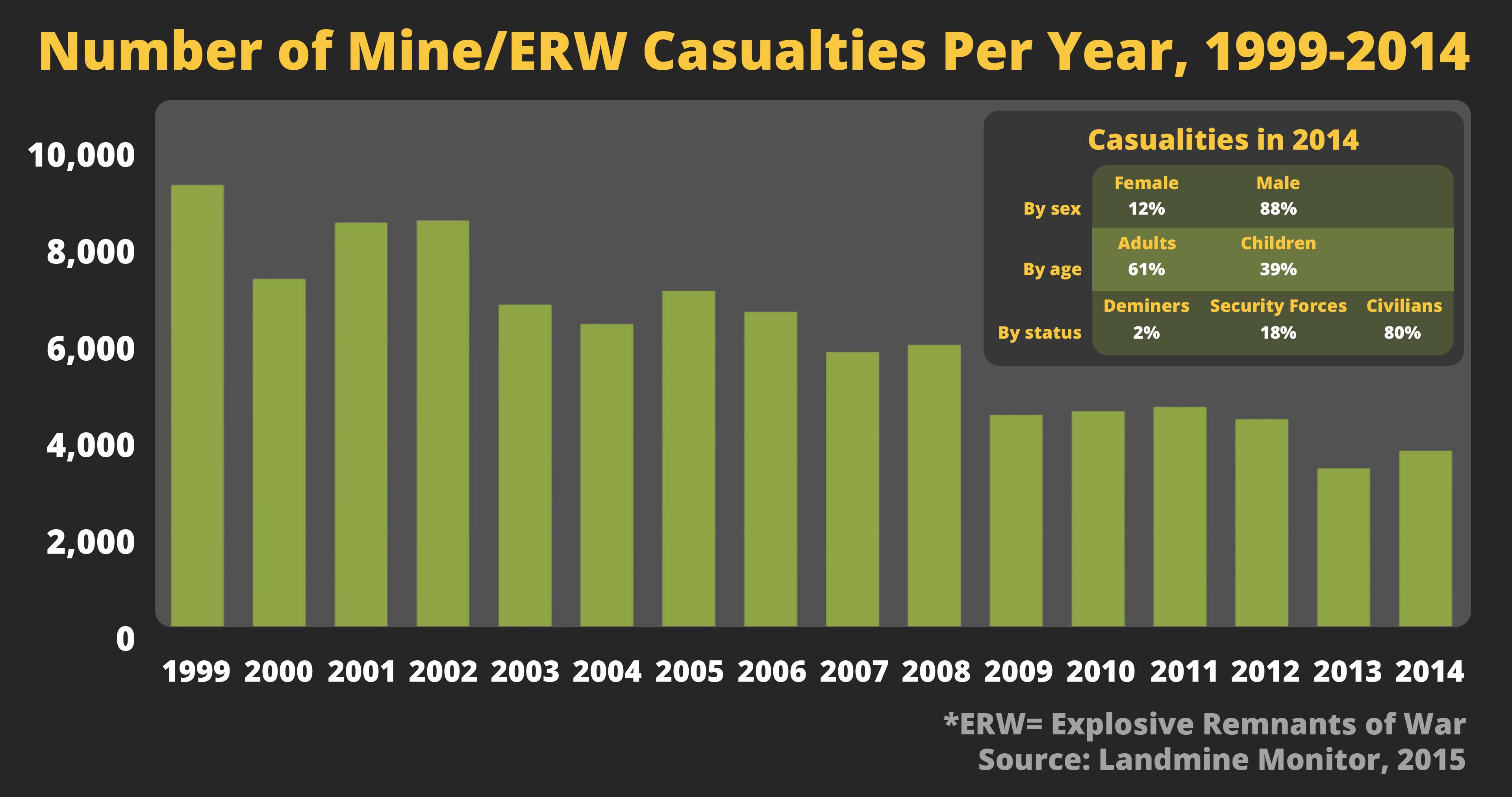

Countries around the world have been unable to develop land for farming or other economic developments due to landmines, which can cause disfigurement and death. Using rats, scientists at the Belgian-based nongovernmental organization Anti-Persoonsmijnen Ontmijnende Product Ontwikkeling, or in English Anti-Personnel Landmines APOPO have been able to find and neutralize tens of thousands of landmines, which have opened land for a variety of important uses. Their rats also save lives by detecting tuberculosis, a deadly disease killing at least 1.5 million people per year. In addition to these rats, other animals have been trained to assist humans with a plethora of tasks, including serving as companions for veterans and becoming service animals for people with disabilities. These accomplishments have been aided by the science of behavior analysis and the principles of operant conditioning.

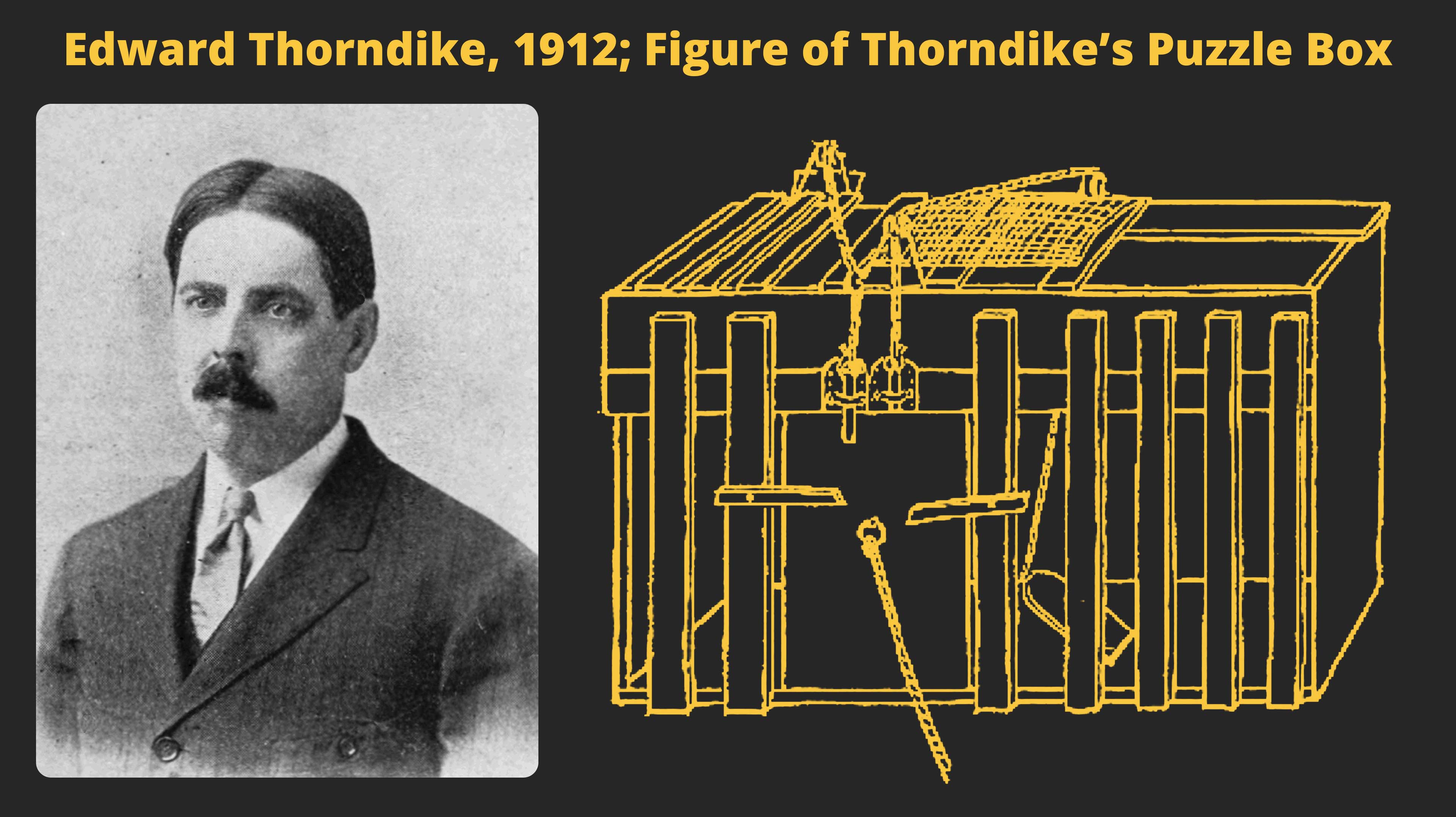

Noted American psychologist Edward Thorndike (1874-1949) studied learning principles using cats enclosed in what he called “puzzle boxes.” Inside the box was a mechanism that the cat could manipulate to open the box, allowing the cat to escape. The cats had motivation to escape, as there were fish treats outside the box. Thorndike found that early on it took cats several hundred seconds to escape, but with subsequent trials the time to escape dramatically decreased. This discovery led Thorndike to propose the “Law of Effect,” which states that behavior that leads to pleasant consequences is more likely to be repeated in the future, and behavior that leads to unpleasant consequences is less likely to be repeated. His work contributed to the beginning of the principles of operant conditioning and the field of behaviorism.

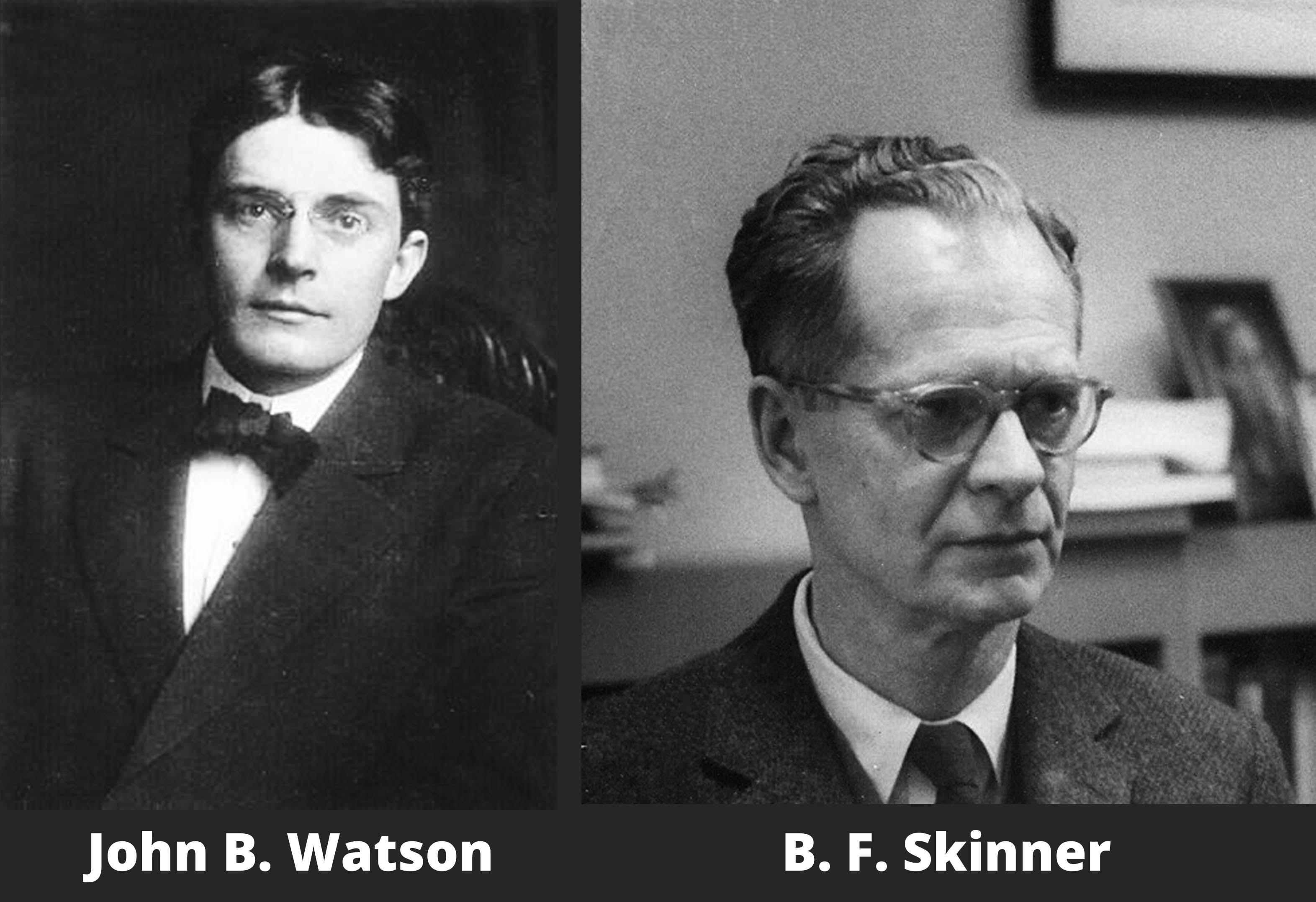

American John B. Watson (1878-1958), one of the world’s most famous psychologists, founded the school of behaviorism in 1913. At the time, the study of psychology was mainly focused on introspection and subjective explanations for the causes of behavior. Watson argued that psychology should focus on observable behavior and avoid studying introspection. He declared that the goal of psychology should be to predict and control (influence or change) behavior, utilizing objective measures of behavior and focusing on how organisms adapt to their environments.

Watson was instrumental in changing how psychologists study, measure, and view the causes of behavior. Both Thorndike and Watson contributed greatly to the understanding of the role the external environment plays in influencing our behavior. However, it was the innovative B.F. Skinner, and those he influenced, who built on the foundation of Watson and Thorndike. Skinner’s work advanced our ability to describe, explain, predict, and influence behavior to improve human and animal lives by arranging our external environment. He founded the field of behavior analysis, which includes the experimental analysis of behavior and applied behavior analysis.

Skinner (1904-90) spent his career studying the principles of learning. He was influenced by Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection, which states that organisms whose traits best allow them to meet the challenges of the environment and reproduce will pass along their phenotype to the next generation. Skinner applied this idea to behavior and proposed that many behaviors were selected by their consequences. Building on Thorndike’s Law of Effect, Skinner focused on the consequences of our behavior and how those consequences influence whether or not a particular behavior is likely to occur again.

Using an enclosed chamber that he designed and built, commonly called a “Skinner Box” or “operant chamber,” he studied the behavior of rats under closely controlled conditions. Rats are easy to care for, their physiology is similar to humans in many regards, and the results from experiments with rats often apply to humans and other organisms. Operant chambers contain response levers, stimulus lights, and mechanisms to deliver food; they are used widely in studying variables that affect learning. By manipulating variables such as hunger level (deprivation and satiation), the number of times a lever had to be pressed to earn food, and even the presence of drugs (e.g., caffeine), Skinner studied operant conditioning. The term “operant behavior” suggests that this type of behavior “operates” on the environment to change it, thereby producing consequences. These consequences operate on our behavior to shape it and influence the likelihood of future occurrence.

- ABC analysis (antecedent/behavior/consequence)

- Motivating operation

- Operant conditioning

- Reinforcers and punishers

- Unconditioned/conditioned reinforcer

Section Focus Question:

How do behaviorists explain the ways a person's actions or reactions can be “conditioned”?

Key Terms:

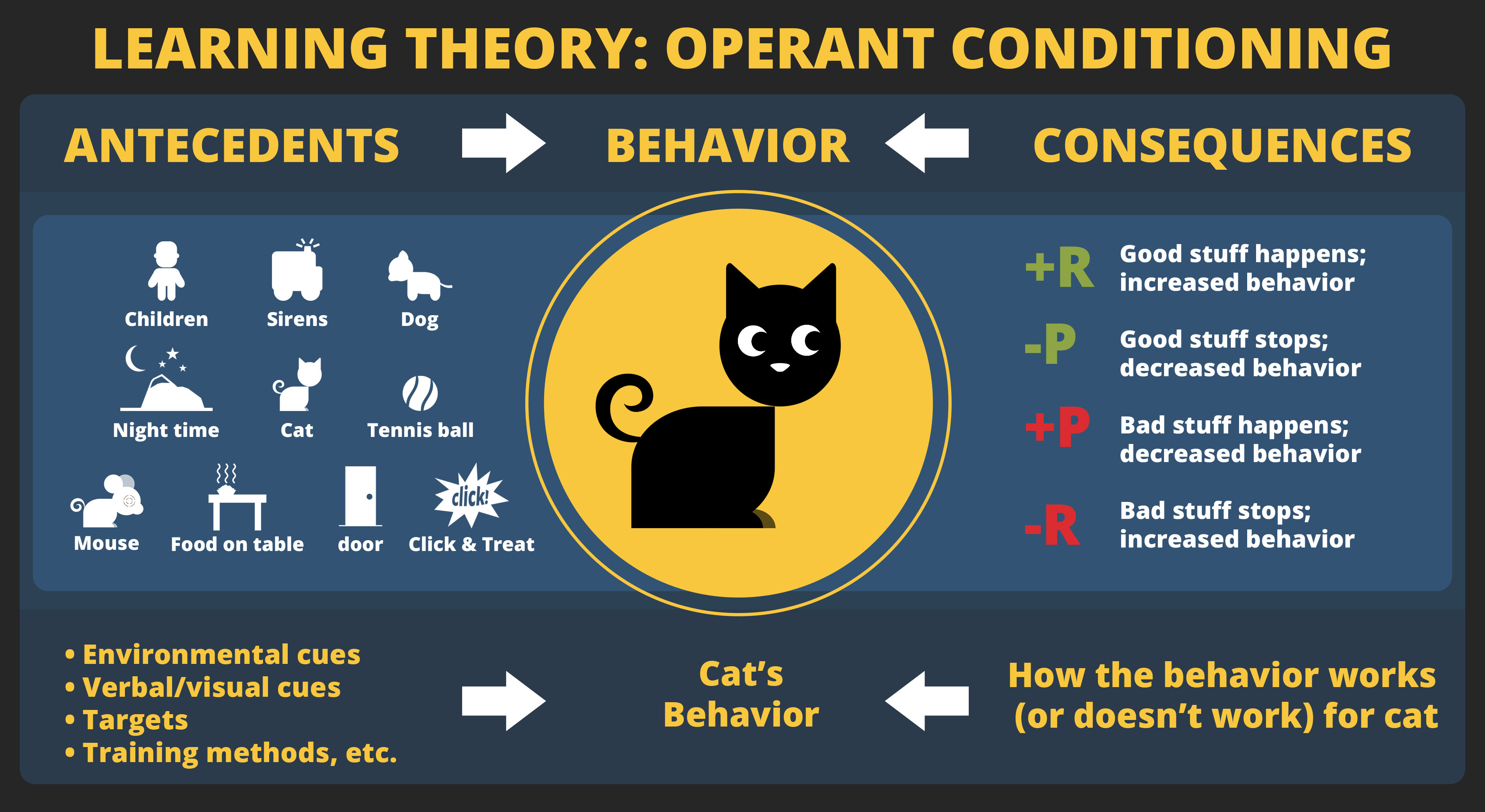

Behavior analysts depict operant conditioning in terms of A-B-C analyses, where A = antecedent, B = behavior, and C = consequence. Antecedents include “motivating operations” (MOs; motives) and “discriminative stimuli” (abbreviated SDs; cues). MOs are events or objects that make certain consequences more or less effective in influencing later behavior; in everyday terms, they change what one wants or does not want. SDs signal that particular consequences are currently more or less available than they were before. “Behavior” refers to non-reflexive, goal-oriented activity in which an organism engages, and “consequences” are the results of behavior.

The consequences of behavior influence the likelihood that the behavior will occur again in the future under similar circumstances. Consequences can increase the future occurrence of a behavior, termed “reinforcement,” or they can decrease the future occurrence of a behavior, termed “punishment.” Let’s analyze a behavior to identify the terms presented thus far. You are in a foreign country, haven’t eaten in 12 hours, and are very hungry (hunger is an antecedent MO). You see a vending machine (antecedent; SD), put your money in and take a bite of the item you selected (behavior). The consequence of taking a bite of the item will either result in an increase or decrease of the future frequency of selecting and eating the item again. If you choose that item again, that item is termed a “reinforcer,” whereas if you do not choose that item again, it is termed a “punisher.”

Reinforcers and punishers vary across individuals and across an individual’s lifetime. That is, what served as a reinforcer or punisher for us at one point in time may no longer do so as we age. Reinforcers and punishers can be described as “unconditioned” and “conditioned.” Unconditioned reinforcers and punishers have the capacity to change our behavior without any prior learning history. Food (in general) is an example of an unconditioned reinforcer, and pain is an example of an unconditioned punisher. Most organisms are born with a capacity for food and pain to function as a reinforcer and punisher, respectively. “Conditioned” reinforcers and punishers acquire their behavior-changing abilities as a result of experience (learning history). Although unconditioned reinforcers and punishers influence our behavior, conditioned reinforcers and punishers influence much more of our daily behavior. Money, grades, and praise are examples of conditioned reinforcers, whereas, hurtful comments from others and time-outs are examples of conditioned punishers. Conditioned reinforcers and punishers gain their ability to control behavior by being paired with unconditioned reinforcers and punishers.

- Landmine detection

- Landmine hazards worldwide

- TB mortality

- APOPO

- Discrimination training

- Positive reinforcement

- Negative reinforcement

- Escape behavior

- Avoidance behavior

- Response cost

Section Focus Question:

Why is the example of APOPO’s HeroRat program a good example of operant conditioning, and how do “positive” and “negative” reinforcers work to shape behavior?

Key Terms:

Let’s use the ABCs of operant conditioning to see how the scientists at APOPO train their rats to detect deadly landmines. The rats are first “socialized,” which means they are handled by humans and become familiar with the sights, sounds, and smells of their environments. Next, food is paired with a special ‘click’ sound (the click is sounded and then followed by delivery of the food), which makes the click a conditioned reinforcer. The rats’ behavior can now be increased by sounding the click after the target behavior occurs. The rats are trained to search for a specific ‘target scent’ to earn their reward (click and food). In this case, the target smell is the explosive compound TNT that is used in landmines. When the rat correctly detects the TNT the clicker sounds and food follows. Due to this pairing, the rats will work for the sound of the click, as long as it is at least periodically followed by the food reward.

To ensure that the rat is actually detecting the TNT (and not just engaging in smelling behavior) they must learn the difference between three different sniffing holes. When the rat momentarily stops over the correct hole containing TNT, the click sound will appear followed by the food reward. This is termed “discrimination training;” the rats learn that sniffing a hole that contains TNT results in reinforcers, and sniffing in a hole not containing TNT does not produce reinforcers. Thus, the smell of TNT is an SD that indicates reinforcers (click and food) are available. The rats are then trained to find the TNT in a sandbox and learn to walk on a leash. The rats indicate that they have found the TNT by pausing over its location (pausing over the location of the TNT is the behavior that is reinforced). Once they pass their exams and are certified, they are promoted to the fields where, across several countries, they aid people in clearing landmines. That is why they have been named HeroRats.

Reinforcement and punishment are both procedures and processes. The procedure of reinforcement for the HeroRats was providing a click sound and food after the desired behavior occurred; the process of reinforcement was the gradual increase in the strength of that behavior (accurate TNT detection). There are four types of consequences: positive and negative reinforcement and punishment. The terms “positive” and “negative” simply refer to whether the reinforcer or punisher was added to, or removed from, the environment after the behavior occurred. Positive reinforcement occurs when an appetitive stimulus (something of value) is added after a behavior occurs, whereas negative reinforcement occurs when an aversive stimulus (something unpleasant) is removed after a behavior occurs. The terms positive and negative should be thought of in mathematical terms, not emotional terms. That is, positive does not mean “good” and negative does not mean “bad.”

The HeroRATs were trained with positive reinforcement because the food and click sound were added to the environment after the behavior occurred. Positive reinforcement can be effective in changing behavior. In fact, it is mandated in US schools that any individual education plan for students must first use positive reinforcement methods to change behavior. That said, negative reinforcement influences much of our daily behavior. Consider the parent in line at the grocery store whose child is throwing a temper tantrum because he or she wants some candy. The child’s behavior is an aversive stimulus for the parent; to get the child to be quiet, the parent gives him or her some candy. If this scenario happens again in the future, we would say that the parent’s behavior of giving the candy was “negatively” reinforced, because the child ceased the tantrum upon receiving the candy (the aversive stimulus was removed). Note, however, that the child’s tantrum behavior was “positively” reinforced because candy was added to his or her environment after engaging in the behavior (an appetitive stimulus was added).

Negative reinforcement can be further divided into “escape” and “avoidance.” Escape behavior refers to behavior that occurs in the presence of an aversive stimulus and results in the removal of that stimulus. The parent’s behavior in the scenario above is an example of escape behavior; giving the candy terminated the aversive stimulus (the tantrum). Avoidance behavior refers to behavior that occurs to prevent the aversive stimulus from occurring. If the parent gave the child something to eat before going into the grocery store to prevent the child from throwing a tantrum, that would be considered avoidance behavior. Note that both escape and avoidance are types of negative reinforcement, and the end result is an increase in the future frequency of those behaviors.

Punishment is the process whereby behavior is weakened and becomes less likely to occur in the future. “Positive punishment” occurs when an aversive stimulus is added to the environment after a behavior occurs. Positive punishment is not recommended for changing behavior because it has many problematic side effects in those who receive the punishment, such as increased aggressive behavior and emotional distress. “Negative punishment” occurs when an appetitive stimulus is removed after a behavior occurs. “Time-out” and “response cost” are two types of negative punishment. With time-out, the individual is removed from an environment where reinforcers are currently available. Response cost occurs when an individual loses an appetitive stimulus after engaging in a particular behavior. Losing car privileges because one missed curfew is an example of response cost. In general, negative punishment is preferable to positive punishment.