Behavioral Pharmacology and How Drugs Influence Behavior

Note to students: The best preparation for taking the reading quiz is to pay close attention to the key terms as you read. Each question in the question banks is directly linked to these key terms and phrases.

Chapter Focus Question:

What three major things has behavioral pharmacology learned about drug addiction in the last 25 years?

- LSD dependency/lethality

- Nicotine dependency/lethality

- Caffeine dependency/lethality

- Heroin dependency/lethality

- Hallucinogen

- Behavioral pharmacology

- Drug self-administration

- Reinforcers

- Abuse potential

- Opiates

- Opioid epidemic

- Naloxone

- Prescription drugs

Section Focus Question:

What are five attributes of drug addiction that are important to know?

Key Terms:

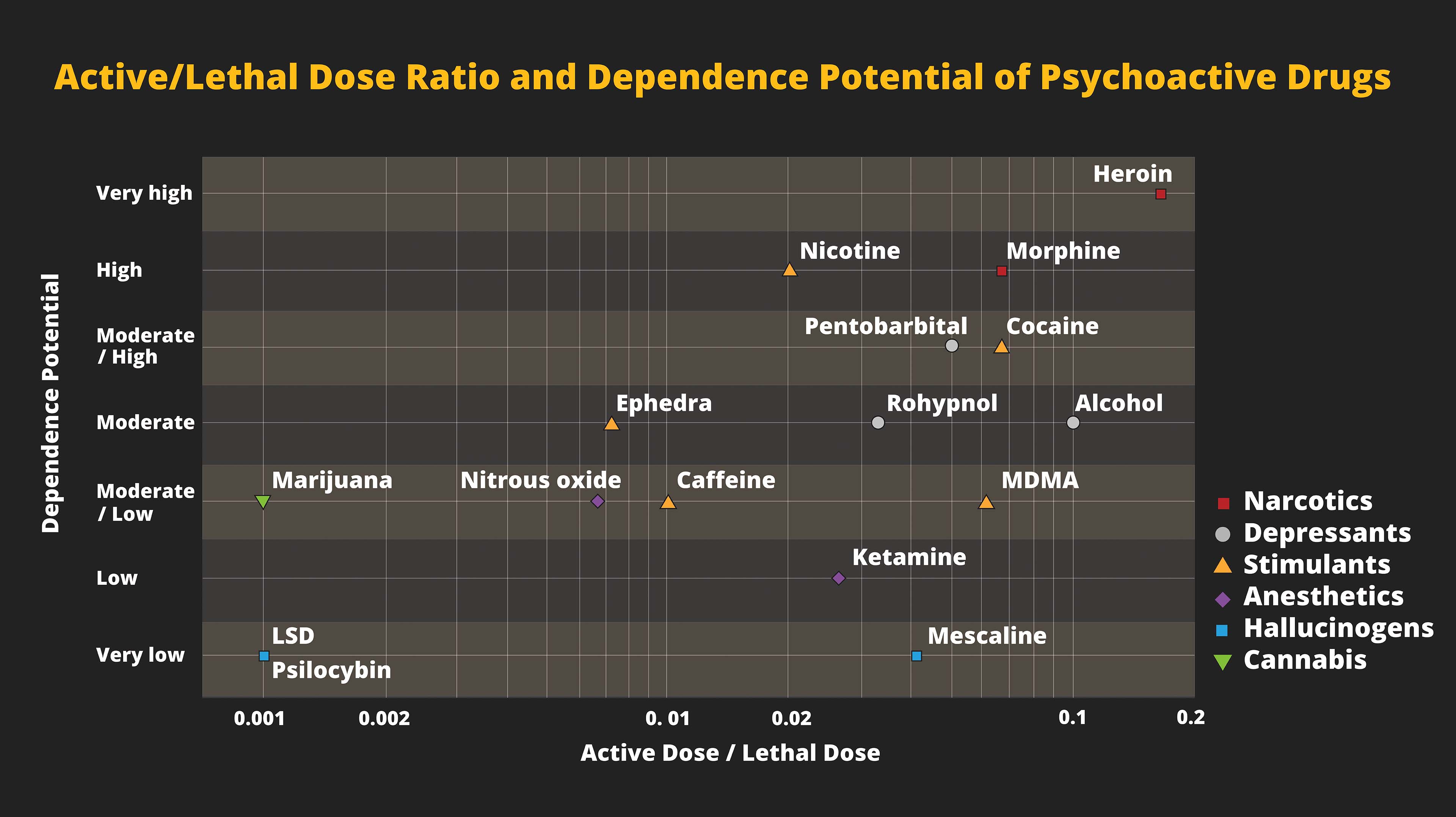

This chart categorizes drugs according to two factors — the lethality of the drug and the addiction potential. On the “x”, or horizontal, axis at the left are drugs, such as LSD, psilocybin, and marijuana, that have low lethality no matter the dose, while drugs that have lethality with higher doses, such as opioids, are on the right. The “y”, or vertical, axis tracks dependence or addiction with LSD/psilocybin at the bottom and heroin at the top. Interestingly, while LSD and heroin track at opposite ends of the spectrum for lethality/addiction — LSD low and heroin high in both variables — the federal Drug Enforcement Administration rates heroin and LSD at the top (Schedule 1) for abuse and dependency, despite the research. Professor Snycerski discusses how science and cultural practices often diverge in our efforts to deal with drugs.

Drugs are ubiquitous in our society. Whether prescribed by a doctor, bought on the street, or found in nature, drugs surround us on a daily basis. Drugs can dramatically affect the way we think, feel, and behave. They can save lives, and they can take lives. Why do some people become boisterous and aggressive when they consume alcohol and others become emotional and depressed? Why do some people become so addicted to a drug that they lose their jobs, families, and homes? How can drugs be used to treat mental disorders or substance abuse? How do we know the effects specific drugs produce? These and many more drug-related questions can be answered through the science of behavioral pharmacology.

Behavioral pharmacology is a field that combines psychology and pharmacology. Using concepts and principles from behavior analysis, researchers study the behavioral effects of drugs in both humans and other animals. Results from studies of the effects of drugs on nonhuman animals, such as rats, pigeons, and monkeys, readily generalize to humans. Moreover, using animals as subjects allows for greater control of the environment in which the drugs are studied. That said, behavioral pharmacologists also study the effects of drugs in human participants. What is fascinating is that in a majority of cases, animals will self-administer (voluntarily take) the same drugs as do humans!

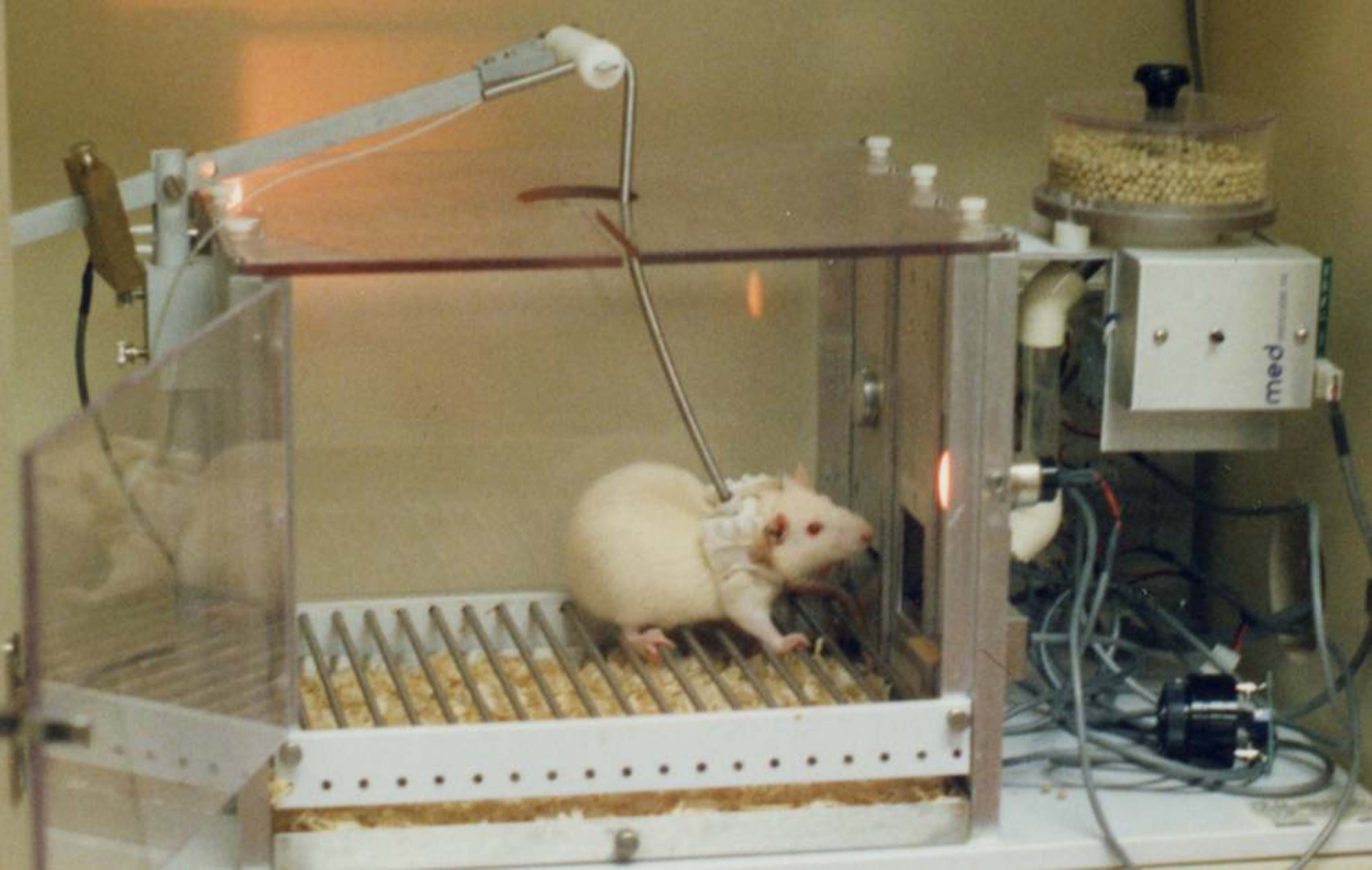

Drug self-administration is one main area of focus in behavioral pharmacology. Rats (and other animals) can be trained to press a lever inside an operant chamber that will result in food delivery. If a rat is deprived of food, it will readily press the lever. To study whether a drug has abuse potential, the lever press can be changed to result in an intravenous delivery of a drug, for example, methamphetamine. If the rat presses the lever repeatedly to receive the infusion of the drug, we say that drug has abuse potential and that the drug is a “reinforcer.” Reinforcers are stimuli or events that increase the future frequency of the behaviors that produced them.

Repeated self-administration of drugs can lead to physical and psychological dependence and tolerance. The opiates, which include heroin and prescription painkillers (like Oxycontin or Vicodin), are the classic example of a class of drugs that produces these effects. When opiates are given frequently they can result in physical dependence wherein cessation of drug taking produces “withdrawal effects.” These effects are unpleasant and painful, which leads the user to re-administer the drug to alleviate those symptoms.

However, repeated use of the drug may also result in “tolerance” to the pleasurable effects of the drug, and this results in the need to take greater amounts of the drug to produce the desired effect. Behavioral pharmacologists use self-administration procedures to study dependence and tolerance and to determine the abuse potential of new compounds. With the exception of some hallucinogens (such as LSD), nonhuman animals self-administer the same drugs as humans (e.g., alcohol, cocaine, heroin, and amphetamines). As with some drug users, if given unrestricted access to drugs of abuse nonhumans will continue to self-administer until they overdose.

- Drug tolerance

- Triggers

- Community reinforcement approach

- Steven Higgins

- Environment’s effect on drug abuse

- Drug dosage

- Drug assays

- Chlorpromazine

Section Focus Question:

What has research found about the effect of environment on drug addiction?

Key Terms:

Drug addiction can be extremely difficult to treat. Even after successful rehabilitation, users often relapse and use again. One explanation for relapse is that users experience “conditioned withdrawal” in the presence of stimuli that were once paired with drug use (also called “cues” or “triggers”). For example, a person addicted to heroin may have undergone a successful treatment and been drug-free for several months. However, if that person encounters somebody using heroin, passes his or her dealer on the street, or even sees a needle, this person could experience physical withdrawal symptoms such as nausea and drug craving. These are often so powerful that the person engages in self-administration of the drug. Behavioral pharmacologists have developed effective drug treatments that focus on desensitizing the client to these cues such that they no longer produce withdrawal symptoms.

Another treatment developed by behavioral pharmacologists is the “community reinforcement approach,” wherein community-based sources of reinforcement are provided in an attempt to compete with drug reinforcers. Clients attend behavioral therapy, receive employment and career counseling, interpersonal relationship counseling, and participate in social and recreational activities. All of these activities provide alternative sources of reinforcement. Research shows that greater access to other forms of reinforcement can decrease drug use.

“Contingency management” is another approach that rewards clients with tangible reinforcers when they provide drug-free urine samples. A variation of this approach, voucher-based reinforcement therapy, was developed by Dr. Steve Higgins to treat cocaine addiction. In this therapy program, clients earn vouchers for their drug-free urine samples. These vouchers can be exchanged for goods or services that are approved by the treatment providers because they are consistent with the treatment goals. The vouchers start out at a small value and, with each consecutive drug-free sample, increase in value. Thus, it “pays more” to stay drug-free longer. If a person relapses and his or her urine shows the drug has been consumed, the value of the voucher resets to the initial low value.

In one demonstration study, 11 out of 13 clients completed 12 weeks of treatment using this approach; whereas only 5 out of 12 were able to complete 12 weeks of treatment in a traditional 12-step program. Additional controlled clinical trials of this behavioral approach have shown it to be more effective than other more common therapies, such as drug counseling.

In addition to studying the abuse potential of drugs and therapies for drug addiction, behavioral pharmacologists also study how drugs affect learning, memory, motivation, and other psychological processes. Drugs produce multiple effects, have dose-dependent and time-dependent effects, and can be toxic at sufficient doses. Therefore, these variables all need to be taken into consideration when attempting to answer the question “What does Drug X do?” For example, a low dose of a stimulant drug may produce a slight increase in heart rate, a subjective feeling of wakefulness, increased attention, and a positive mood. That same drug, however, in a larger dose can produce a dangerous increase in heart rate, insomnia, confusion, and aggressive or combative behavior. Thus, the dose of a drug can dramatically change the behavioral and psychological effects it produces.

Drug assays (drug measuring or monitoring) can be used with both human and nonhuman animals to measure the effects of recreational drugs as well as drugs used as medicines. One procedure used to determine how drugs affect memory is “delayed matching to sample.” In this procedure, subjects are presented with a sample stimulus on a computer screen for a few seconds after which it disappears. Next, after a predetermined delay length (e.g., five seconds), the original stimulus appears with three different comparison stimuli. The subject has to correctly identify the sample stimulus after the delay and in the presence of the comparison stimuli. That is, the subject must remember the sample stimulus.

Using a variation of this procedure, researchers determined that the drug chlorpromazine impaired the memory of individuals diagnosed with intellectual disability. When they were taken off the drug, they were able to more accurately identify the correct sample stimuli. Therefore, this assay not only quantified memory capacity, it also showed that some drugs used as medicines can have unwanted deleterious side effects.

- Learning and memory

- Drug combinations

- Effects of alcohol addiction

- Multiple effects of addictions

- Progressive ratio

- Ecstasy

- Schedule 1

- Psychedelic drugs

- MDMA

- Magic mushrooms

Section Focus Question:

How are drugs used to treat drug addiction?

Key Terms:

Procedures for assessing drugs effects on learning and memory can also be combined to study how a drug impacts both. One interesting study by Higgins and colleagues assessed the effects of cocaine and alcohol, both alone and in combination, on learning and memory. It is often the case that people who use drugs of abuse engage in simultaneous polydrug use; that is, they take more than one drug at the same time. The drugs may produce similar or opposite effects, depending on the class of drugs. For example, the polydrug combination of alcohol and cocaine is well-established. In fact, the participants in the Higgins study had a history of simultaneously using alcohol and cocaine in combination.

To measure learning, participants in the Higgins study had to learn a new sequence of responses on a keyboard; the sequence changed daily. To measure memory, they had to learn one sequence on the keyboard and that remained unchanged daily. Relative to baseline, when alcohol was tested alone, it impaired learning in that participants made more errors. Cocaine tested alone did not produce impairments in learning compared to baseline measures. However, when cocaine and alcohol were tested together, the errors in the learning sequence dropped significantly. That is, the cocaine attenuated the impairing effects of alcohol on learning. When tested under the memory sequence, alcohol and cocaine, both alone and in combination, produced little impairment.

These findings demonstrate two important tenets in behavioral pharmacology: (1) behaviors that are well-established are less disrupted by drugs, and (2) drugs are often used in combination to offset or manage particular side effects produced by each single drug. In fact, users of this combination specifically report that using the cocaine helps manage the deleterious effects of alcohol.

The motivation to use drugs is also studied by behavioral pharmacologists. Alcohol is one of the most widely used drugs, and it continues to be used and abused by college students, among others. Many people report using alcohol as a way to relax and to feel more comfortable when socializing. Alcohol is a depressant drug, and at low doses it can cause relaxation. However, as the dose increases it can also cause people to engage in behaviors that they typically would not otherwise do. People often make bad decisions while under the influence of alcohol and that is due to the antipunishment effects alcohol produces. That is, alcohol results in disinhibition. This example illustrates another important principle, which is that drugs have multiple effects.

Motivation for drug use is often studied using a “progressive ratio” (PR) schedule of reinforcement. Under this procedure, the number of responses required to produce a reinforcer systematically increases across a test session. For example, a rat may be placed in an operant chamber and it has to press a response lever to obtain a reinforcer. In this case, that reinforcer would be an intravenous administration of a drug. Under a PR 25 schedule, the first response requirement to earn an infusion of the drug is 25 lever presses, the next is 50, then 75, and so on. This procedure measures the “value” of the reinforcer, or how hard the subject is willing to work to earn the reinforcer. One study using this procedure with humans found that a subject pressed a key sequence on a computer over 80,000 times for almost nine hours in order to obtain access to pentobarbital (which produces effects similar to alcohol).

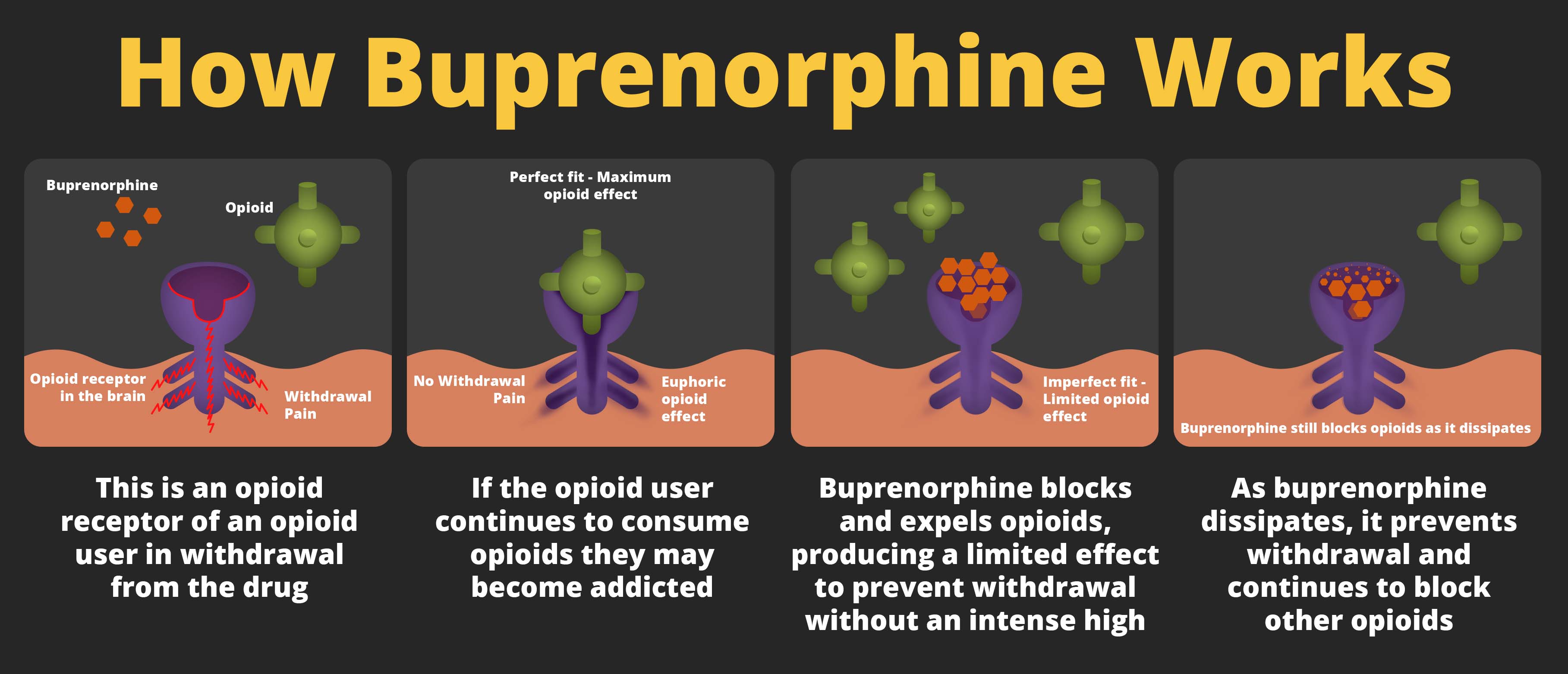

Finally, drugs are also used to treat substance abuse and other mental disorders. For example, Suboxone is a prescription drug that contains buprenorphine and naloxone. It is used to treat addiction to opiate drugs. It prevents the withdrawal symptoms, and, when used in conjunction with other forms of behavioral therapy, can help those dependent on opiates manage their addiction and lead more fulfilling lives. Unfortunately, however, this drug can also be abused, so careful monitoring by a physician is required. Drugs used to treat mental illness can be effective in managing a wide variety of disorders including depression, schizophrenia, attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder, and anxiety disorders, among others.

More recently, behavioral pharmacologists have been studying the effects of psychedelic drugs for treating conditions such as post-traumatic-stress-disorder (PTSD). While psychedelic drugs, such as LSD, were studied widely in the 1950s and 1960s for their potential therapeutic effects, cultural changes resulted in an approximately 40-year absence of such research.

Today, therapists and researchers are using methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, ecstasy) in a treatment package that includes cognitive-behavioral therapy for individuals with PTSD. Clients have shown remarkable improvements in their symptoms after this therapy. Why? MDMA produces feelings of emotional warmth, empathy toward others, decreased anxiety, and a general sense of well-being. Thus, while under the influence of MDMA, clients are able to more comfortably communicate with their therapist about the factors that caused the PTSD because the MDMA prevents them from feeling anxious or afraid.

These treatments have been so successful that there are ongoing clinical trials to treat veterans with PTSD using this approach. Another psychedelic drug, psilocybin (found in “magic mushrooms”), has recently been shown to be effective in treating nicotine addiction. This is an exciting time in the field of behavioral pharmacology as researchers continue to find promising applications for psychedelic drugs.